По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

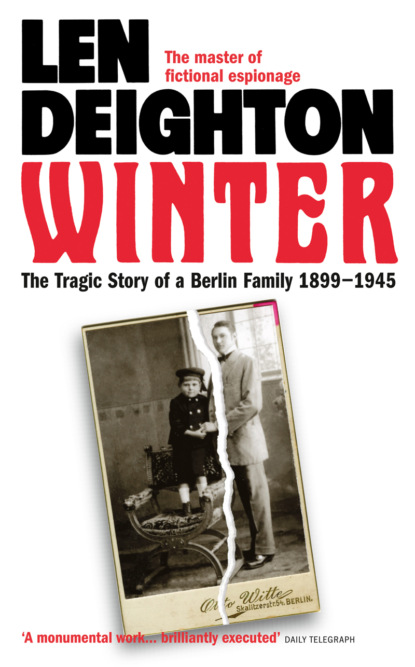

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Then Peter and Paul went off to find Fritz Esser. He was in his boat shed, chopping wood and bundling it for kindling. He said he was sorry that the Valhalla had never been found again. Perhaps it would turn up. Wrecks along this coast reappeared as flotsam on the beaches after the autumn storms. ‘See you next year,’ the boys told him.

‘I won’t be here next year. My papers will come for the army, but I won’t go. I’ll be on the run.’

‘Where will you hide?’ asked Pauli. They had both come to admire the surprising Fritz Esser, but little Pauli hero-worshipped him.

‘People will shelter me,’ said Esser confidently. ‘Liebknecht says the Party will help.’

In the corner of the old hut Peter spied splinters of beautifully finished white hull, just like that of the Valhalla, but he didn’t inspect them closely. Sometimes it is better not to know.

Along the beach they saw the pig man. He grinned and waved a knife at them: they waved back to him and fled.

The boys said goodbye to Omi, too. They heard their father whisper to Mama that by next year Omi might no longer be here. They kissed Omi goodbye and promised to see her next year.

Veronica went up to the little turret room and spent a few minutes alone there. She would never see the Englishman again: she knew that now. She could never go away without the children, and yet she could not bring herself to take them away from her husband.

1914

War with Russia

Despite all his previous misgivings, Paul was not unhappy at his military school. In fact he rather enjoyed it. He enjoyed the unvarying routine, and he appreciated the way everyone accepted his scholastic limitations. It was all very strange, of course. Most of the other boys had come from Kadettenvoranstalten – the military preparatory schools – and they were used to the army routines and the shouting and marching and the uniforms that had to be so clean and perfect. Cleanliness had never been one of Paul’s priorities, but luckily a boy named Alex Horner, who’d come from the military prep school at Potsdam, helped the fourteen-year-old through those difficult early days of April when they first arrived.

Nothing at Gross-Lichterfelde was quite as he’d imagined it. He’d expected to be trained as a soldier, but his daily routine was not so different from that of any other German high school except that the teachers wore uniforms and he was expected to march and drill each afternoon. He’d hoped to be taught to shoot, but so far he’d not even seen a gun.

His father had told him that the Emperor had to approve each and every entrant to this, the Prussian army’s only cadet school, and that only the sons of aristocrats, army officers and heroic lower ranks could be admitted. The truth was somewhat different: most of the cadets were, like Paul, the sons of successful businessmen or of doctors, lawyers, bureaucrats and even wealthy farmers. Only a few of the boys had aristocratic families and most of these were the second or third sons of landowners whose estates would go to their elder brothers.

Alex Horner was typical of these disappointed younger sons. His father owned four big farms in East Prussia and had served only a couple of years in the army. Alex owed his place at Lichterfelde to the efforts of an uncle who was a colonel in the War Office.

It was Alex who always pulled Paul out of bed when reveille was sounded at six o’clock and got him off to the washroom before the cadet NCO came round to check the beds. A quick wash and then buttons. It was Alex who showed him how to use a button stick so that no metal polish marked his dark-blue tunic: a sleepy boy at the other end of the room who once tried polishing his buttons last thing at night instead of before breakfast discovered how quickly brass dulled, and served a day under arrest. Thanks to Alex, Paul was usually one of the first outside ready to be marched off to the standard Lichterfelde breakfast of soup and bread and butter. But the most important reason that Pauli had for liking Alex Horner was that Alex had seen Pauli crying his heart out on the night he first arrived, and Alex had never told a living soul.

Marching back from breakfast along the edge of the parade ground that morning in July, Paul remembered April 1, the day he’d arrived. That was over three months ago; it seemed like years. His father had insisted that Mama shouldn’t come, and Paul appreciated his father’s wisdom. He was quite conspicuous enough in the big yellow Italian motorcar with Hauser at the wheel. The Winters had lost two chauffeurs, who went to drive Berlin motor buses, so Hauser, the valet, had now learned to drive the car, and he’d promised to teach the boys, too, as soon as they were tall enough to reach the foot pedals.

Paul could look back now and smile, but that very first day at the Königlich Preussische Corps des Cadets at Lichterfelde – or what he’d now learned to call Zentralanstalt – had come as a shock. Although the band was playing, it didn’t offset the fuss the parents were making with their tearful mothers and odd-looking fathers. The poor boys knew they would be teased mercilessly about every aspect of their parents, and everything they did and said within the hearing of their fellow recruits.

Now it was summer, almost eight o’clock, and the sun was very low and blood red in an orange sky. Soon it would be hot, but the morning was cool, and a march to breakfast and back again was almost a pleasure. Crunch, crunch, crunch. Paul had learned to take pride in the precision of their marching. For the boys with years of cadet training already behind them it was all easy, but Paul had had to learn, and he’d learned well enough to be commended and allowed to shout orders to the cadets on one momentous occasion. Halt! There was much stamping of boots while the cadet NCO saluted the lieutenants, and the lieutenants saluted the Studiendirektor. Then, file by file, all two hundred cadets marched into the chapel for morning service.

‘Something has happened,’ whispered Alex. The chapel was gloomy; the only light came through the small stained-glass windows.

‘War?’ said Paul. The darkness and the low, vibrant chords of the organ provided a chance for furtive conversations. There was a clatter of hobnailed boots when one of the seniors stumbled as the back row was filled. Then the doors were closed with a resonant thump.

The boy next to him was a senior – one of the Obertertia, the boys permitted to go to rifle shooting in the afternoons. ‘The Serbs have replied to the Austrian ultimatum.’

‘Everyone knows that,’ whispered a boy behind them, ‘but will the wretched Austrians fight?’

‘Quiet!’ called a cadet NCO. ‘Horner and Winter, report to me after Latin class.’

Paul stiffened and looked down at his hymnbook. It was always like that: the junior year got punished and the senior boys escaped. Was it because their sins were overlooked, or had they become more skilled at talking without moving their lips? Alex kicked Paul in the ankle; Paul glanced at him and grinned. He hoped it would mean nothing worse than being put on half lunch ration – the other boys always helped out and the last time he’d eaten even better on punishment than he normally did – but if he got a three-hour arrest this afternoon he’d be late home, and then he’d have Father to answer to. Paul hated to be in disfavour with his father. His brother, Peter, had always been able to shrug off those fierce paternal admonitions but Paul wanted his father to admire him. He wanted that more than anything in the whole world. And it was Friday: this weekend he’d arranged for Alex Horner to come home with him, and a detention now would mess everything up.

‘Hymn number 103,’ said the chaplain mournfully, but no more mournfully than usual.

Paul and Alex escaped with no more than a fierce reprimand. Luckily their persecutor wasn’t one of their own NCOs but a senior boy who didn’t want to miss his riding lesson. Normally at 4:30 p.m. – after doing two hours of prep – there was drill on the barracks square, but at noon this day the boys were told that they were free until dinner, and that those with weekend passes could go home. It was another sign that something strange was in the air.

And as Alex and Paul went to their train at the Lichterfelde railway station they noticed that civilians deferred to them in a way that was unusual. ‘After you young officers,’ said a well-dressed businessman at the door of the first-class compartment. There was an element of mockery in this politeness, and yet it was not entirely mockery. The ticket inspector touched his hat in salute to them. He’d never done that before.

The boys did not read. They sat erect, conscious of their uniforms, styled like those of the post-1843 Prussian army, rather than the new field-grey ones. Military cap, white gloves, blue tunic, poppy-red cuffs and collar with the double gold braid that marked Lichterfelde cadets, and on the black leather belt a real bayonet.

In the other corner of the compartment, the man who’d ushered them inside sat reading a copy of the daily paper. The big black headline in Gothic type said ‘Russia mobilizes.’

From the Potsdamer railway station they walked through the centre of Berlin: past the big expensive shops of Leipziger Strasse, and then along Friedrichstrasse. Everywhere they saw groups of people standing around as if waiting for something to happen. There were more women on the streets nowadays – shopping, strolling, exercising dogs; the shorter skirts enabled women to be out and about in a way they never had before. The narrow Friedrichstrasse was always busy, of course; here were offices, shops, cafés and clubs, so that it never stopped, night or day. But today it seemed different, and even the wide Unter den Linden was filled with aimless people. At the intersection of the two streets – one of the most popular spots in all Berlin – was the boys’ destination: the Victoria Café and the best ice cream in town.

They got a table outside on the pavement and watched the traffic and the restless crowds. A No. 4 motor bus went past; on its open top deck were half a dozen soldiers. They were flushed of face and singing boisterously. The bus was heading towards the Friedrichstrasse railway station, where there were always military policemen. Alex predicted that they would be in cells within half an hour, and there was little chance that he would be wrong.

Everything was bright green, the lime trees were in full leaf, and the birds were not frightened of the noise, not even of the big new motor buses. Only when the band marched past did the birds fly away. Alex said the band was that of the 3. Garde-Regiment zu Fuss marching back to its barracks at Skalitzer Strasse. They wore white parade trousers and blue tunics and gleaming helmets, and the music sounded fine. Behind them was a company of infantry in field grey. They looked tired and dusty, as if they’d been on a long route march, but when they got to the corner of Friedrichstrasse there were some cheers from civilians standing there, and the soldiers seemed to stiffen up and smile.

The waiter brought the boys the big platter of ice cream they’d so looked forward to on this hot day and they started eating greedily. At the next table two men were arguing about whether Russia had really mobilized or whether it was just another rumour or another way of selling newspapers. New editions of the daily papers were appearing on the streets every hour, and the vendors came calling the new headlines with a desperate urgency.

‘Will they send us to the front?’ Paul asked his friend between mouthfuls of ice cream. Alex’s time at the military prep school and the skills he’d already shown made him an authority on all things military, and Paul always deferred to him.

‘Not right away,’ said Alex, finishing the last of his chocolate ice cream and starting on the raspberry one. ‘But they’ll need officers once the war starts. Perhaps they’ll graduate us quickly.’

‘No one could be commissioned before they were seventeen at least, could they, Alex?’

‘I’m not sure,’ said Alex. ‘But if we fight the Russians they’ll need everyone they can get. The Russians have a very big army. My father will have to go: he has a reserve commission in the cavalry. He wants me to go into the cavalry, but I’m going to fly in the army airships.’

‘My father has a factory that builds airship parts,’ said Paul. He wiped a dribble of ice cream from his chin. ‘My brother likes airships, but I wouldn’t much like to fly. I prefer horses.’ In fact, Pauli found the prospect of flying in an airship quite terrifying, but that wasn’t something he’d confide to anyone: not even Alex.

After finishing their ice cream they walked up Unter den Linden, just to see what was happening. From the Victoria Café they went past the cathedral, over the ‘museum island’, and then returned to the enormous block of the Royal Palace. The sentries had been doubled outside the palace, and a crowd was staring up at the empty stone balcony, hoping the Kaiser would appear, but the Kaiser was at sea with his Fleet. Some of the crowd began to sing ‘Deutschland über alles’, until a dozen policemen appeared and after a lot of shouted orders and pushing, moved them along.

When the boys eventually got back to the Winter house it was four o’clock. Hauser opened the door. Hauser was growing a beard; progress was slow and each weekend Paul noted its development. ‘The master is in the study with Herr Fischer,’ said Hauser, ‘and your mama has a headache and is sleeping. Your father said you are to see Nanny right away.’

Paul took his friend up to the top floor. It was a big house, as Alex, on his first visit here, noticed. It had the smell of newness. There had been many such fine new homes built in Ku-damm over the last twenty years or so. There was wood panelling, rich carpets and wonderful furniture. And although Alex’s own home in far off Königsberg had fine furniture and just as many servants, if not more, the Winter house was in such faultless condition that he was frightened of leaving a footprint on the perfectly brushed carpet or a fingermark on the polished handrails. But Alex was enough of a snob to know that these big houses near the Ku-damm were the mansions of the nouveaux riches. The established tycoons had villas in Grunewald, and the aristocracy their palaces on the Tiergarten.

Paul found his nanny in her room, packing her case. ‘I’m off, back to Scotland, young Paul,’ she said. She looked at him as if expecting a reaction but, not knowing what he was supposed to say, Pauli stared back at her without expression. ‘Be good to your mother, Pauli,’ she said. Her eyes were red. She leaned over and gave him a peck on his forehead. Then she reached for the cup of tea she always liked to drink at four o’clock in the afternoon. She put condensed milk in it. Afterwards, for all his life, Paul never smelled condensed milk without remembering her. ‘It will seem strange after nearly sixteen years with you all.’ She gulped some tea and said, ‘Your father thinks it’s best, and he knows.’ Her voice was rough. She was on the verge of tears, but Paul didn’t realize that. He watched her folding her aprons and packing them carefully into the big scarred suitcase. He’d never seen inside the case before: outside it was stained and scuffed and covered with torn hotel labels, but inside its leather was like new. Dutifully the boys stayed with her watching her pack, until Paul glanced at Alex and made a face. Then, unable, to think of anything more appropriate, he said, ‘Goodbye, Nanny,’ and with no more than a perfunctory kiss on her cheek he took Alex off to his ‘playroom’, which had been called the nursery when Nanny first arrived so long ago, before Paul was born.

While the two boys were setting out the train set, downstairs in his study Winter was drinking brandy with his guest, Erwin ‘Fuchs’ Fischer. The lunch had been a protracted one, as lunches tended to be when Winter wanted to discuss business, for Winter was not a man who rushed his hurdles.

‘The loss of both naval airships last year – how did the Count take that?’ asked Fischer. Asking how von Zeppelin had reacted to the crashes was just a roundabout way of asking how Winter had reacted.

Winter smiled. He was a dapper man and his hair, now parted on the left side of his head and allowed to grow longer, had greyed at his temples. But he was handsome – undeniably so – even if he was somewhat demonlike with his pointed chin and dark, quick eyes. And always he was optimistic. It seemed as if nothing could get him down. ‘Zeppelins have flown thousands and thousands of kilometres since 1900. Those sailors in L1 were the very first deaths in any Zeppelin airship. And that was due to a squall; there was no structural failure.’

‘You always were a good salesman, Harry.’ Fischer grinned. He had now inherited the big complex of metal companies that his father had built up in over thirty years of trading. Harry Winter was trying to persuade him that a big cash investment in his aluminium business would be to their mutual benefit, but Fischer wasn’t so sure. He didn’t know much about the light-alloys business and he was frightened of bringing ruin to his father’s work. The added responsibilities had aged him suddenly. The great helmet of hair had now thinned so that his pink scalp was visible, and his eyes were dark and deep-set.

Winter said, ‘A light cruiser – the Köln – radioed a storm warning, but…Well, we don’t know what happened after that.’

‘Except that L1 crashed into the sea and fourteen sailors died.’ Fischer scratched his nose. He didn’t want to do business with Harald Winter. He enjoyed his friendship, but he didn’t trust his judgement. Winter was too impulsive.

‘Airships are safe, Foxy. But freak weather conditions are something no one can provide against.’

Fischer sipped his brandy. The food and drink were always first class at Winter’s place, he had to admit that. And he lived in grand style. Fischer looked round at the magnificent inlaid desk, the leather-bound editions of Goethe, Schiller and Shakespeare that he actually read, and the exquisite Oriental carpets that he wasn’t afraid to walk upon. Winter was not known for giving big parties or having a box at the opera, but in his own quiet way he lived very, very well. ‘Then, just five weeks later, the navy lost the L2. It burned and fell from the sky. How does the Count explain that one, Harry?’