По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

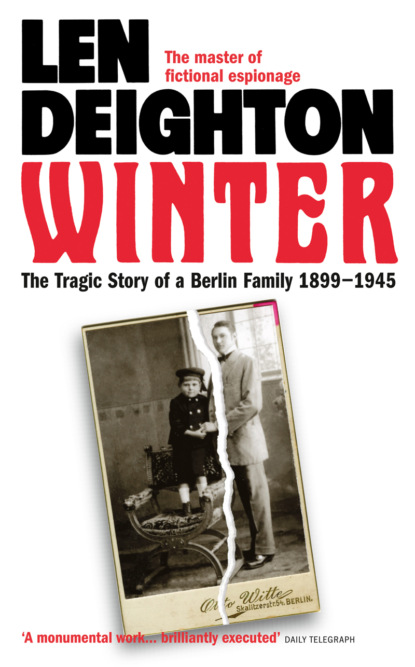

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘They took her up to “pressure height” too fast, and hydrogen was valved from the gas cells.’

‘I read all that, Harry. But damnit, why did the hydrogen ignite?’

‘The navy fitted big windscreens to the gondolas to provide a bit of protection from the air stream. The leaking gas went along the underside of the envelope – combining with enough air to make a very explosive mixture. From the keel those damned windscreens took it down to the gondola and the red-hot parts of the engines.’

Fischer stroked his lips nervously. ‘The navy say that von Zeppelin approved their modifications,’ persisted Fischer. If Harald Winter wanted him to invest in his aluminium company, Fischer might let him have some small token payment for the sake of their friendship, but it would be no more than the company could afford to write off. And even for that Fischer was determined to drive a hard bargain.

‘No,’ said Winter. ‘He simply sent his congratulations on the way the finished airship looked.’

‘Having a stand-up row with Grossadmiral von Tirpitz at the funeral didn’t improve matters for him.’

‘Count Zeppelin’s an old man,’ said Winter.

‘We’re all getting older, Harry, even you. What were you last birthday, forty-four?’

‘Yes,’ said Harry.

‘And I’m sixty-two. We’ve known each other a long time, Harry. I should be getting ready for retirement, not learning how to run this damned company of mine.’

Pleased with the opening thus provided, Winter said, ‘It makes sense: an investment with me would make good sense, Foxy.’

‘Aluminium? My instinct is to diversify out of metals.’

‘Exactly what I’m offering. The five million Reichsmarks you invest will be for an aero-engine company and an air-frame assembly plant.’

‘You said it was for aluminium.’

‘No, no, no. That’s just the collateral I’m offering to you. The extra money is for airplane manufacture.’

‘Haven’t you got enough troubles in aviation, Harry? Two naval rigids crashed. Who’s going to buy your aluminium now?’

‘The navy are committed to the airship programme. They have built airship bases along the northern coast and are building more. The money is allotted and the personnel are being trained. They can’t stop now. They’ll buy more and more. And so will the army.’

‘I suppose you are right. And now it’s to be airplanes too?’

‘Airplanes will be needed to protect the airships and to attack enemy airships too.’

‘So the war is certain, is it Harry? Not just newspaper talk?’ To some extent this was provocation, but it was also a question. Harry Winter mixed with the military people; he’d know what the current thinking was. ‘Is war a part of the company’s prospectus?’

‘You sell the navy a battle cruiser and they use it for twenty-five years. Sell the army artillery pieces and they last ten or fifteen years.’ He sipped his drink. ‘But aircraft are fragile.’

‘And are expendable in war in a way that battleships are not expendable?’

‘War or no war, airships and airplanes get damaged easily. Men have to be trained to fly, so there are many crashes. Everyone knows that, including the men who fly them. A constant supply of new machines is going to be required by the military.’

‘You’re a cold-blooded devil, Harry.’

‘I don’t make the decisions, Foxy, I simply react to events.’

‘I can’t give you an exact answer, Harry. My son Richard will have to agree. But we’ll participate.’

Harald Winter relaxed. He’d got what he wanted. He knew Foxy would try to whittle the five million down to one million or less. But what Foxy didn’t realize was that Harry only wanted his name. He had several investors who’d readily put their money in when they heard that Fischer was convinced. ‘Is Richard a director now?’

‘I’m not going to keep my son out of the business the way my father excluded me right up to the day he died. He’s thirty-three years old. Richard is a junior partner and gets a chance to decide on everything important. What about your two boys?’

‘Little Paul seems happy enough at Lichterfelde. He’s a genial chap, always laughing. The army will be good for him; he has no head for business.’

‘And Peter?’

‘He’ll go to university next year and then he’ll get a position with me. I’m arranging for him to be excused his military service and simply be replacement reserve. There are plenty of men for the army: the population has grown by leaps and bounds. And my factories are now vital to the army and navy. If he works hard I’ll make Peter a junior partner.’

‘Lucky boy. Is that what he wants to do?’

‘You know what young people are like, Foxy. He has this mad idea of becoming a musician. He doesn’t understand what a musician’s life is like.’

‘Is he talented?’

‘They tell me so, but talent is no guarantee that a man will earn a living. On the contrary, the more talent a man has the less likely he is to do well.’

‘Surely not?’

‘The scientists in my factory, the engineers who design the engines and the structures: what talents they have, and yet they will never get more than a simple living wage. Most of them could make far more money in the sales department, but they are too interested in their work to change. Talent is an impediment to them. Look at all the penniless artists desperate to sell their work, and the musicians who beg in the street.’

‘And so you’ve forbidden Peter to study music?’ asked Fischer provocatively.

Winter knew that Fischer was baiting him in his usual amiable way but he responded vibrantly. ‘If he wants to study music, that’s entirely up to him. But he can’t expect to enjoy himself playing music while others work to supply him with money.’

‘You’d cut him off without a penny?’ said Fischer with a smile. ‘That’s hard on the boy, Harry.’

‘If he wants to inherit the business, he must work. I have no patience with people like Frau Wisliceny, who gives the boy these crazy notions.’

‘Frau Wisliceny – Professor Wisliceny’s wife? But her “salon” is the most famous in Berlin. The world’s finest musicians take tea there.’

‘Yes, Frau Professor Doktor Wisliceny, I should have said…. And so do all sorts of other riffraff: psychologists, painters, novelists, poets and even socialists.’

Fischer decided not to reveal the fact that he had tea there regularly, too, and spent happy hours talking to the ‘riffraff’. ‘But if Frau Wisliceny thinks your son Peter has talent …What does he play?’

‘Piano. I won’t have one in the house, so he goes there to practise. My wife encourages him, I’m afraid. At first they thought that they’d force me to buy one for him but I wouldn’t yield. Professor Wisliceny must be a strange fellow to put up with it. How did he make his money?’

Fischer smiled. ‘Ah, that rather goes against your theory. The professor is a very clever chemist…synthetic dyestuffs.’

‘He made money from that?’

‘These aniline dyes save all the time, trouble and expense of getting dyes from plants, minerals, or animals. He makes a lot of money selling his expertise. You should bear him in mind, Harry, when you are making Peter toe the line.’

Winter was not amused. ‘I’m not talking about scientists. I don’t want a musician in the family.’

‘Too bohemian?’