По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

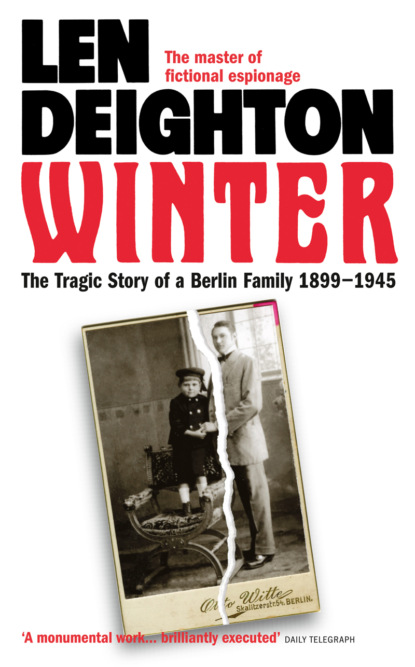

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I found it under the bed, Mama.’ He showed her the wristwatch proudly. It was a fine Swiss model with a leather strap and roman numerals like the church clock.

‘Oh my God!’ said his mother.

‘It belongs to Mr Piper, Mama. I noticed him wearing it.’ He looked at his mother. He’d never seen her so horror-struck.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I borrowed it from him. Mine stopped last night at dinner.’

‘Shall I give it to him?’ said Pauli.

‘No, give it to me, Pauli. I’ll tell the chambermaid to put it in his room.’

‘I know which is his room, Mama.’

‘Give it to me, Pauli. He might be angry if he hears I’ve dropped it on the floor.’

‘I won’t tell him, Mama.’

‘That’s best, Pauli.’ His mother clutched the watch very tight and closed her eyes, the way children do when making a wish.

Three days after Papa arrived, everyone went to Kiel and stayed in a hotel. It was a momentous trip. Mama wore her new ankle-length motoring coat and gauntlet gloves. Papa drove the car. Its technology was no longer new, but he loved the big yellow Itala and clung to it, even though some people thought he should drive a German car. It was the first time he’d taken the wheel for such a long journey, but he knew that Glenn Rensselaer was able to make running repairs and the chauffeur was ordered to stay near the telephone at Omi’s house just in case something went very badly wrong. Glenn sat beside Harald Winter, the Englishman and Mama at the back, the two children in the folding seats. There were no servants with them. The servants had gone by train. As Harald Winter said, ‘It will be an adventure.’

It was not just an excursion. Harald Winter didn’t make excursions: he had an appointment in the Imperial Dockyard. The next day, while a sea mist cloaked the waterfront and muffled the sounds of the dockyards, he met with a young Korvettenkapitän and two civilian officials of the purchasing board of the Imperial German Navy. Harald Winter had not been forthcoming about the subject of his discussion. It concerned the prospect of a naval airship programme, and that was categorized as secret. The department was already named; it was to be the Imperial Naval Airship Division – but so far it consisted of little beyond a name on the door of one small room on the wrong side of the office block. Last year the appearance of the German army’s airship Z II at the ILA show in Frankfurt am Main had made the future seem rosy. But this year everything had gone wrong. The destruction of that same airship – one of the army’s two zeppelins – in a storm near Weilburg an der Lahn in April was followed by the loss of Count Zeppelin’s newly built Deutschland in June. To make matters worse, a competitor of Zeppelin had built a semi-rigid airship that not only beat Zeppelin’s endurance record by over an hour but arrived at the autumn army manoeuvres complete with its own mobile canvas shed. Now all the admirals and bureaucrats who’d delayed the decisions about purchasing zeppelins were congratulating themselves upon their farsightedness.

But while Harald Winter was sitting across the table from the earnest young naval officer and two blank-faced officials, his wife, children and guests were on the waterfront admiring the assembled might of the new Germany navy.

‘Look at them,’ said Glenn Rensselaer, indicating a dozen great grey phantoms just visible through the mist. ‘German shipyards have never been so busy. The one anchored on the right is a dreadnought.’ He used his field glasses but failed to read any name on the warship.

‘Three dreadnoughts last year, and four built the year before that,’ said Piper. Today the Englishman was looking like a typical holidaymaker, in his striped blazer and straw hat. ‘That makes the German navy exactly equal to the strength of the Royal Navy.’ He took the glasses Glenn Rensselaer handed him but didn’t use them to look at the ships.

‘No,’ said Glenn. ‘You British have eight dreadnoughts and at least three more on the slipways.’ He wore a cream pin-striped flannel suit with his straw boater at an angle on his head. The incoming sea-mist had made it too cold for such summer attire on this promenade. He had a long yellow scarf and now he wound it twice round his neck. Veronica noticed and wished she’d chosen something warmer. The cotton dress with its broderic anglaise trimmings was made specially for this holiday, but the dressmaker had not calculated on the spell of cold weather.

The Englishman nodded. ‘Perhaps you’re right.’

‘And what exactly is a dreadnought?’ said Veronica.

‘Oh, Mama!’ said young Peter, looking back from where he was climbing on the railing to get a better view. ‘Everyone knows what a dreadnought is.’ Little Pauli climbed up beside his brother.

‘It’s a new type of battleship,’ said the ever-attentive Piper.

‘They all look the same to me,’ said Veronica.

‘Maybe they do,’ said Rensselaer, ‘but when the British built HMS Dreadnought in 1906 it made every other capital ship obsolete. Steam-turbine engines, bigger guns and all to a common calibre: faster and more deadly than anything previously built. Now the strength of any navy is measured by the number of dreadnoughts they have. It took that Kaiser of yours a couple of years to get started, but now he’ll bust a gut rather than let the Royal Navy outgun him.’

‘Get down, Peter,’ Veronica called to her son. ‘You’ll make your trousers dirty and we haven’t brought any more with us.’ The Englishman smiled at her. ‘It’s so difficult without the servants,’ said Veronica.

Glenn Rensselaer took back his field glasses again and studied the big dreadnought. ‘Do you think they brought her through the canal, or is she too big?’ Now that the Nord-Ostaee-Kanal directly connected Germany’s North Sea Fleet with the Baltic Fleet, it had vastly increased Germany’s naval potential. Still using the field glasses, Glenn Rensselaer eventually answered his own question: ‘Too big, I think. That’s probably why they are working so hard to make it wider and deeper.’ Even without the glasses one could see the sailors moving about the deck in their white summer uniforms. From the size of the sailors it was easy to judge the dimensions of the huge battleship. ‘She’s big,’ said Glenn Rensselaer, ‘very big.’

Veronica, hampered by the fashionable hobble skirt, had walked on and now Piper followed her. The crisp cotton dress with its high tight lace collar and the lovely new hat with silk bow and artificial flowers made her look wonderful, and she knew it. The others were out of earshot by the time he caught up with her. It was the first chance for Veronica to speak privately with the Englishman since her husband had arrived, but she said only, ‘I wish my brother wouldn’t speak so disrespectfully of His Majesty. It has such a bad effect on the children.’

‘I know, Mrs Winter, but your brother means no harm, I’m sure of that.’ He smiled at her and she smiled back.

She felt very happy. It really didn’t matter what was said. She loved the Englishman and he loved her. There was no need to say it. There was no need to say anything at all, really.

They’d hoped that the mist would lift, but it was one of those days when the Kiel Bight remains shrouded in fog until nightfall. When they got back to the hotel, Harry had still not returned from his meeting. Alan Piper ordered tea. Glenn chaffed him about this curious English ritual, but they all sat together in the glass-sided lounge, exchanging small talk, until the Englishman took the restless boys outside to the promenade for another look at the warships.

Left without them in the lounge, Veronica turned to her brother and said, ‘There won’t be a war, will there, Glenn?’

He looked at her and took his time before replying. ‘Dad is convinced that there will be. The folks would like you to come back home; I guess they tell you that in their letters.’

‘Yes, they do.’ She poured more tea for herself. She didn’t want it, but she was nervous.

‘This year you didn’t get to see them in London.’ He sat back in the armchair and crossed his legs. Big bony skull, wide cheekbones, and easy smile – sometimes he looked so like Father, and so like little Paul. She’d not noticed before how much of a Rensselaer her son looked.

‘It would be so easy for them to come here.’ She didn’t want to talk about her parents. It would make her feel guilty, and she didn’t want to feel guilty.

‘Dad’s not too fond of the Germans; you know that. And since the sudden death of the King of England, the Kaiser is determined to prove himself the master of Europe. Dad says he’s dangerous, and I agree.’

‘It’s just not fair,’ said Veronica. ‘Everyone blames the Kaiser, but all he wants to do is make Germany as strong as the other powers. What’s so bad about that?’

‘It’s the way he goes about it: he struts and rants and always wears that damned army outfit with the spiked helmet. That military posturing doesn’t go down well in Paris and London and New York. They like statesmen to wear dark suits and carnations and make speeches about peace and prosperity.’

‘Harry says that European armies are only suited for colonial wars.’

‘Suited, maybe. But they are fast becoming equipped for something far more destructive. What about these airships that can float right over big towns and toss explosives down on the city hall? Look out the window and see the guns on that dreadnought: one of those ships could shell a coastal city and remain out of sight while doing it. And what about these huge conscript armies that Prussia has had for over a hundred years? You don’t need conscript armies for colonial scraps. Right? Back home I’ve been down through the South…I walked through the ruined streets of Richmond, Virginia, and it’s enough to make you weep. The same goes for cities in the Carolinas and Georgia. What is it – fifty years back? And they still haven’t rebuilt everything that the fighting destroyed. And the bitterness remains…. It’s terrible, and that’s the kind of war that these damned Europeans are going to have, unless I miss my guess.’

‘You frighten me with such talk, Glenn.’

‘I promised Dad that I would have a serious word with you. Don’t you ever miss your friends and your folks and your family? How can you be happy with all these foreigners all the time?’

‘I don’t want to say anything hurtful, Glenn, but these “foreigners” are my friends and my family now.’ Glenn would never understand how much Berlin meant to her. She loved the city: the opera, the ballet, the orchestras, the social life, and the intellectual climate. She loved the crazy, uncomplaining, shameless Berliners, with their irrepressible sense of humour. She loved the friends she’d made and her husband, and her incomparable sons. How could Glenn expect her to abandon everything that made life worth living and start all over again in a cultural wasteland like New York City?

‘Do you mind if I smoke my pipe? I can’t think properly without a taste of Virginia.’ From the pocket of his double-breasted flannel jacket he took a tobacco pouch, safety matches, and a curly meerschaum pipe.

‘I don’t mind, but maybe it’s not permitted here. There’s a smoking room at the back of the restaurant.’

‘Baloney! People smoke everywhere nowadays. People smoke on the street in New York, even women.’

‘That sounds horrible.’

He lit the pipe, which was already charged with tobacco. ‘It was the flies that got me started,’ he said between puffs at the pipe. ‘I was working on a ranch in Texas, and the smoke was the only way you could keep them out of your eyes and mouth. I saw guys go crazy.’

‘I’d love to see New York again,’ she admitted with what was almost reluctance. ‘Just for a visit.’

‘You’d never recognize New York City these days, sis. I know your husband is reckoned a big shot in that automobile of his. But I stood in Herald Square and saw it jammed so tight with automobiles that none of them could get going.’ He laughed and puffed his pipe. He’d affected a pipe when he first came to see her in Germany, the year after Peter was born; Glenn was seventeen then. He’d tried to look grown-up but he’d choked on the tobacco smoke, and she’d brought him fruit when he went to bed feeling sick. She felt a sudden pang of regret that she’d left her family so young. They’d grown up without her, and she’d grown up without them.

‘And Dad and Mama like it in New York?’ she asked.

‘They don’t spend much time downtown any more. But, sure, Dad likes it. While your Harry was betting on airships, Dad was betting on the automobile. He invested in steel, oil and rubber and is getting richer by the minute.’ He puffed on his pipe again. ‘You didn’t mind my bringing Boy with me?’