По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

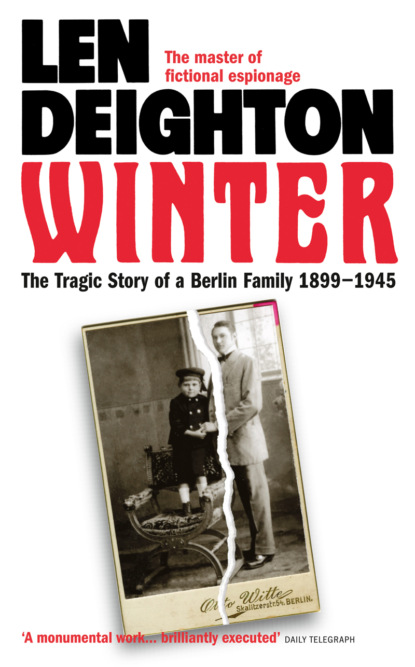

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Peter! Peter!’ There was nothing but milky-looking waves and mist, and the boat raced on before the gusting wind. Pauli jumped to his feet to pull the sail down, and before he could move aside the tiller was torn from his hands strongly enough to whack him across the leg, so that he cried out with the pain of it. He couldn’t reef in the sail, he knew he couldn’t: it was something his brother always attended to. ‘Peter! Please, God, help Peter.’

Some distance away from the boat, Peter came to the surface, spluttering and desperately flailing his arms so that he got no support from the water. Still encumbered in his yellow oilskin jacket, he slid down again into the hateful green, chilly realm from which he’d just fought his way. He closed his mouth only just in time to avoid a second lungful of sea water, and let the water close over him, twisting his arms in a futile attempt to claw his way back to the surface. The green water darkened and went black.

When Peter saw daylight again, the waves were still high enough to smash across his head. Like leaden pillows, they beat him senseless and scattered a million grey spumy feathers across the heaving sea. He could see no farther than the next wave and hear nothing but the roar of the wind and the crash of water. It seemed like hours since he’d been washed overboard, and – although it was no more than three minutes – he was physically unable to save himself. His small body had already lost heat, till his feet were numb and his fingers stiffening. Besides the temperature drop, his body was bruised and battered by the waves, and his stomach was retching and revolting at the intake of cold salty water.

There was no sign of the Valhalla, but even had it been close there would have been little chance of Peter’s catching sight of it through the grey-green waves and the white, rainy mist that swirled above them.

No one ever discovered why little Pauli jumped off the stern of the Valhalla and into the raging water that frightened him so much. Many years later explanations were offered: his wife said it was a desperate wish to destroy himself; a prison psychologist interpreted it as some sort of baptismal desire; and Peter – who heard Pauli talk about it in his sleep – said it was straightforward heroism and in keeping with Pauli’s desire to be a soldier. Pauli himself said it was fear that drove him from the safety of the boat into the water; he felt safer with his brother in the sea than alone on the boat. But that was typical of Pauli, who tried to make a joke out of everything.

Little Pauli was a strong swimmer and unlike his brother, he was able to divest himself of the oilskin and prepare himself for both the coldness and the strength of the currents into which he plunged. But, like his brother, he was soon disoriented, and couldn’t see past the big waves that washed over him constantly. He swam – or, rather, flailed the heaving ocean top – hoping he was heading back towards the coast. Above him the clouds raced overhead at a speed that made him dizzy.

The squall kept moving. It passed over them as quickly as it had come, moving out towards Bornholm and Sweden’s southern coast. The racing clouds parted enough to let sunlight flicker across the waves, and then Pauli caught sight of the yellow bundle that was Peter.

Had Peter been completely conscious, it’s unlikely that the smaller child would have been able to support his brother. All drowning animals panic; they fight and thrash and often kill anything that comes to save them. But Peter was long past that stage. He’d given up trying to survive, and now the cold water had produced in him that drowsiness that is the merciful prelude to exposure and death.

Peter’s yellow oilskin had kept him afloat. Air was trapped in the back of it, and this had pulled him to the surface when all his will to float had gone. They floated together, Pauli’s arm hooked round his brother’s neck, the pose of an attacker rather than a saviour, and the other arm trying to move them along. The coast was a long way away. Pauli glimpsed it now and again between the waves. There was no chance of swimming that far, even without a comatose brother to support.

They were floating there for a long time before anything came into sight. It was a boy at the oars of a brightly painted rowboat, trying to get to the Valhalla, who saw first a yellow floppy hat in the water, and then the children, too. The oarsman was little more than a child himself, but he pulled the two children out of the water and into his boat with the easy skill that had come from doing the same thing with his big black mongrel dog, which now sat in the front of the boat, watching the rescue.

The youth who’d rescued them was a typical village child: hair cut close to the scalp to avoid lice and nits; teeth uneven, broken and missing; strong arms and heavy shoulders, his skin darkened by the outdoors. Only his height and broad chest distinguished him from the other village youths, that and the ability to read well. To what extent it was his height, and to what extent his literacy, that gave him his air of superiority was debated. But there was a strength within him that was apparent to all, a drive that the priest – in a moment of weakness – had once described as ‘demoniacal’.

The seventeen-year-old Fritz Esser looked at the two half-drowned children huddled together in the bottom of his boat and – despite the pitiful retching of Peter and the shivers that convulsed Pauli’s whole body – decided they were not close to death. He rowed out to where the poor old Valhalla had settled low into the water, its torn sail trailing overboard and its rudder carried away. ‘It will not last long,’ he said, ‘it’s holed.’ Pauli managed to peer over the edge of the rowboat to see what was left of their lovely Valhalla, but Peter was past caring. Esser, aided by the black mongrel, which ran up and down the boat and barked, tried to get the Valhalla in tow, but his line was not long enough, and finally he decided to get the two survivors back to dry land.

He put them in an old boat shed on the beach. It was a dark, smelly place; the only daylight came through the chinks in its ill-fitting boards. Inside there was space enough for three rowboats, but it was evident that only one boat was ever stored here, for most of the interior was littered with rubbish. There were furry pieces of animal hide stretched on racks to dry. There was flotsam, too: a life preserver lettered ‘Germania – Kiel’, torn pieces of sails and old sacks, broken oars and broken crates and barrels of various sizes arranged like seats around a small pot-bellied iron stove.

Esser wrapped sacking round the boys and poked inside the stove until the sparks began to fly, then tossed some small pieces of driftwood into it and slammed it shut with a loud clang. The necessity of closing the stove became apparent as smoke from the damp wood issued out of the broken chimney. It was only after the fire was going that the boy spoke to them. ‘You’re the Berlin kids, aren’t you? You’re from the big house where old Schuster does the garden. Old Frau Winter. Are you her grandchildren?’ He didn’t wait to hear their reply; he seldom asked real questions, they found out soon enough. ‘You come here with your mother, and the flunkeys, and your father comes sometimes, always in some big new automobile.’

Peter and Pauli were huddled together under some sacking that smelled of salt and decaying fish. As the stove flickered into life, and the air warmed, the hut became more and more foul. But the children didn’t notice the odour of old fish or the stink of the tanned hides. They clung together, cold, wet and exhausted; Pauli was looking at the flames in the tiny grate, but Peter’s eyes were tightly closed as he listened to Fritz Esser’s hard and roughly accented voice.

‘I hate the rich,’ Esser said. ‘But soon we’ll break the bonds of slavery.’

‘How will you do that?’ asked Pauli, who, typically, was recovering quickly from his ordeal. It sounded interesting, like something from his 101 Magic Tricks a Bright Boy Can Do.

Esser wracked his brains to remember what the speaker from the German Social Democratic Party had actually said. ‘Capitalism will perish just as the dinosaurs perished, collapsing under the weight of its own contradictions. Then the working masses will usher in the golden age of socialism.’

Half drowned he might be, but Pauli could perceive the majesty of that pronouncement. ‘Is that how the dinosaurs perished?’ he asked.

‘You can scoff,’ said Esser. ‘We’re used to the sneers of the ruling classes. But when blood is flowing in the gutters, the laughing will stop.’

Pauli had not intended to scoff but decided against saying so while the role of scoffer commanded such a measure of Esser’s respect.

‘We have a million members,’ Esser continued. He spat at the stove and the spittle exploded in steam. ‘We’re the largest political party in the world. Soon they’ll start to arm the workers and we’ll fight to get a proper Marxist government.’

‘Where did you find out all this?’ Pauli asked. It sounded frightening but the strange boy was not unfriendly: just superior. His chin was dimpled and his brown eyes deep and intense.

‘I go to meetings with my father. He’s been a member of the SPD for nearly ten years. Last year Karl Liebknecht came here to give a speech. Liebknecht understands that blood must flow. My father says Liebknecht is a dangerous man, but my uncle says Liebknecht will lead the workers to victory.’

‘Did your father tell you about the dinosaurs and the blood in the streets and all that?’ asked Pauli.

‘No. He’s soft,’ said Esser. He stoked the fire to make it flare. ‘My father still believes in historical evolution. He believes that soon we’ll have enough deputies in the Reichstag to challenge the Kaiser’s power. If Germany had a proper parliamentary democracy, we’d already be running the country.’

Pauli looked at his saviour with new respect. It would be just as well to remain friends with a boy who was so near to running the country. Peter had opened his eyes. He had not so far joined the conversation, but it was Peter who, having studied Fritz Esser, now identified him. ‘You’re the son of the pig man, aren’t you?’

‘Yes, what of it?’ said Fritz Esser defensively.

‘Nothing,’ said Peter. ‘I just recognized you, that’s all.’ Peter coughed and was almost sick. The salt water was still nauseating him, and his skin was green and clammy to the touch, as Pauli found when he hugged his brother protectively.

For Pauli and Peter – and for many other local children – the pig man was a figure of rumour and awful speculation. A small thickset figure with muscular limbs and scarred hands, he was not unlike some of the more fearful illustrations in their books of so-called fairy stories. The ‘pig man’ wore long sharp knives on his belt and went from village to village slaughtering pigs for owners too squeamish, or too inexperienced with a knife, to kill their pigs for themselves. He was to be seen sometimes down by the pond engaged on the lengthy and laborious task of washing the entrails and salting them for sausage making. So this was the son of the pig man. This was a boy who called the pig man ‘soft’.

In an unexpected spontaneous gesture of appreciation, Pauli said goodbye to Fritz Esser with a hug. Forever after, Pauli regarded Fritz Esser as the one who’d saved his life. But Peter’s goodbye was more restrained, his thanks less effusive. For Peter had already decided that little Pauli was his one and only saviour. These varying attitudes that the two boys had to the traumatic events of that terrible day were to affect their entire lives. And the life of Fritz Esser, too.

It was the pig man himself who took the boys home. Still wrapped in the fusty, stinking old sacks that gave so little protection from the remorseless Baltic wind, they rode on the back of his home-made cart drawn by his weary horse. It was more than seven kilometres along the coast road, which was in fact only a deeply rutted cart track. The smell of rancid fish and pork turned their stomachs and they were jolted over every rut, bump, and pothole all the way. When they got to Omi’s, the pig man and his son were given a bright new twenty-mark gold coin and sent away with muted thanks.

It was only after the Essers had gone that the two children were scolded. Who would pay for the boat? How did they come to fall overboard? Didn’t they see that a storm was coming up? How could they not come directly home after being rescued? All three women asked them more or less the same questions; only the manner of asking was different. First came the regimental coldness of Omi’s interrogation, then the operatic hysteria of Mama’s, and finally that of their Scots nanny, who, after their hot bath with carbolic soap, put them under the cold shower and towelled them until their skin was pink and sore.

The children took their chastisings meekly. They knew that such anger was just one of many curious ways in which grownups manifested their love. And they’d long ago learned how to wear a look of contrition while thinking of other things.

Now that they no longer had the Valhalla, the children spent their days on the beach. They walked back along the coast road to Fritz Esser’s boathouse. Very early each morning, Esser went out in his boat to fish. He caught little: he had neither tempting bait, good nets, nor the skills and patience of the successful fisherman.

The boys always arrived in time to welcome him back. But Fritz never showed any disappointment when his long hours of work had provided nothing in return. He was always able to manage the crooked smile that revealed a wide mouth crowded with teeth. Every day, of course, the children hoped to see him towing the Valhalla back to them. And each day their hopes diminished, until finally they went to Fritz just for something to do.

Despite the disparity in age, Fritz Esser enjoyed the company of the two children. He let them help him with painting and repairing the boats he was paid to look after. He showed them how to sew up torn sails and caulk the seams of boats that belonged to holidaymakers who’d left them too long out of the water. And all the time he lectured them with the political ideas that came from the booklets he read and the conversations he liked to listen to in the bar of the Golden Pheasant on the Travemünde road, and to the words of his hero Karl Liebknecht.

At the back of the Golden Pheasant there was a big room that was used for weddings and christenings and meetings of the SPD. That was where, last year, Fritz had listened enraptured to the fiery little Karl Liebknecht. In his pince-nez, neatly shaped black moustache, well-brushed black suit and high, stiff collar, this thirty-nine-year-old member of the Prussian Diet looked more like a clerk than a revolutionary, but from his very first words his speech revealed his passions. He denounced the international armaments industry, ‘the clique who mint gold from discord’. He denounced the Kaiser and Bendlerstrasse, where the generals ‘at this very moment are planning the next war’. He denounced the Russian Tsar and all the ‘parasites’ that made up Europe’s royal families. He denounced the capitalists who owned the factories and the police who were their lackeys. He denounced the rich for exploiting their riches and the poor for enduring their poverty.

A big crowd filled the Golden Pheasant that Friday evening. Most of them had come because he was the son of the great Wilhelm Liebknecht (close friend of Karl Marx and a leader of the short-lived revolutionary republic of Baden), not because they wanted to hear this arrogant and unattractive man, whose only notable achievement so far was to have served an eighteen-month prison sentence for treason.

Karl Liebknecht had none of the qualities that a successful orator must have. His clothes made him look more like one of the cold-eyed bureaucrats they all feared and detested than like a man who would lead them to the golden land they were looking for. His educated Hochdeutsch and his manner – urban if not urbane – set him apart from this audience of fishermen and agricultural workers. Liebknecht’s message didn’t appeal to men who were looking for immediate improvement in their working conditions rather than an ultimate world revolution.

Only the very young have time enough for the sort of promises that Karl Liebknecht gave his audience that night. And only a few local youngsters like Fritz Esser were moved by this strange man.

Although the Winter boys had only a hazy idea of what it was all about, something of the excitement that Fritz Esser showed was communicated to them. And Fritz liked striding up and down declaiming the principles of Marxism to this enraptured audience of two. Pauli loved the sounds of Esser’s words, though the fiery rhetoric of hatred held no meaning for him. Peter sensed the underlying belligerence, but Fritz Esser’s flashes of easy humour and his simple charm won him over. And when Esser told them that as fellow conspirators they mustn’t repeat a word of what he said to the policeman, to their family, to any of their household, or even to anyone else in the village in case Fritz was sent to prison, the two boys were totally devoted to him. What a wonderful thing it was to share a secret with a boy who was almost a man. And what a secret it was!

During the final week of their summer vacation, ‘Uncle Glenn’ arrived. Veronica’s younger brother, Glenn Rensselaer, had a habit of turning up unexpectedly all over the world. The first Veronica heard about his visit to Europe was a telegram from the post office of a liner due to arrive at Hamburg next day: ‘Arriving Thursday with friend. Love, Glenn.’ There was a flurry of domestic preparations and for Veronica, speculation, too. Who was the friend and was this just Glenn’s jocular way of announcing that he had come to Europe on his honeymoon?

The speculation ended when Glenn arrived Friday noon, together with an Englishman named Alan Piper. They’d met on the ship coming over from New York: ‘The Kaiserin Auguste Victoria: twenty-five thousand tons. The biggest liner in the world and she’s German.’ It was typical of Glenn that he delighted in the achievements of the Old World almost as much as those of his own countrymen. Glenn had insisted that, since Piper had a month or two to spare before reporting back to the Colonial Office in London, he should accompany him on his tour of Germany, beginning at the house in Travemünde.

Alan ‘Boy’ Piper spent much of his time apologizing for all the extra work and trouble he was causing to the household. He apologized to Veronica so many times that Glenn finally said, ‘Don’t be so goddamned British. They have slaves to do all the work in this country. And Veronica loves a chance to speak a civilized language.’

He was right about his sister. Her mother-in-law had not been well for a few days and was allowed only bread and beef broth, having it served in her upstairs room. So Veronica played hostess to the unexpected house guests, and there was no need to speak anything but English.

Veronica adored her young brother but she was also enchanted by the shy Englishman. He was a little older than Veronica, an unconventionally handsome man with short brown – almost gingerish – hair, a lean bony face, and curiously youthful features that had long ago earned him his nickname ‘Boy’. He insisted that his life had been uneventful compared with her brother’s. From Merton College, Oxford, he’d gone to South Africa, and stayed there working as a colonial government official, although, as Glenn pointed out, he’d been there right through some of the bloodiest encounters of the Boer War.

‘He’s a soldier of fortune, like me,’ said Glenn Rensselaer.

‘Nothing as exciting as that, I’m afraid,’ said Piper modestly. ‘My father was a government official in Africa, and so far I have simply followed in his footsteps.’ He smiled. He had the face of a youngster – fresh and optimistic, and unwrinkled despite the African sun.

‘So what are you doing in Germany, Mr Piper?’ said Veronica. She took care to address him as ‘Mr Piper’, and yet there was a mocking note in her voice that some might have said was flirtatious. ‘Is it another excursion among the natives?’