По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

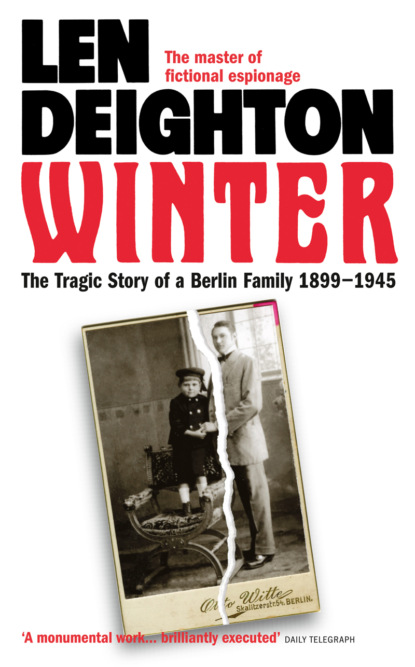

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Indeed not, Mrs Winter. I’m on leave. This visit to Germany, as delightful as it is already proving to be, was quite unplanned. When I returned to London to start this year’s leave of absence, I was very disappointed to learn that I would not be returning to Africa. The two Boer Republics we fought, and the Cape and Natal, become what is to be called the Union of South Africa. I would like to have been there to see it.’

‘South Africa’s loss is our gain,’ said Glenn.

‘I will drink to that,’ said Veronica.

The Englishman picked up his glass, looked at her and saw those wonderful smoky-grey eyes, and, after a fleeting moment, smiled.

Veronica looked down as she drank her wine, and yet she could feel the Englishman’s eyes upon her and despite herself, she shivered.

‘My life has not been nearly so colourful as your brother’s, Mrs Winter. I believe him to be one of the most extraordinary men I’ve ever met.’

‘Really?’ She was pleased to look at her brother and smile. ‘What have you been up to, Glenn?’

Piper answered for him. ‘He’s been everywhere and done everything. He’s even panned for gold on the Klondike.’

‘And a lot of good it did me: I finally sold out my claims for three hundred dollars and some supplies.’

‘He’s worked for Henry Ford and turned down a job with the U.S. Army team that surveyed the Panama Canal. He’s broken horses, repaired automobiles, and even flown an aeroplane.’

‘An airplane?’ said Veronica; even she could still be surprised by Glenn’s doings.

‘Just the once,’ said Glenn. He bent forward and forked some more cold pork, without waiting for the table maid to offer it, trying to cover his embarrassment at Piper’s laudatory remarks. Having swallowed it, he took a sip of wine and wiped his lips. ‘There was a guy on the ship coming over, a rancher. I’d worked for him a couple of times. He spent half the voyage filling Boy’s head with tales about me. You know how Texans like to spin a yarn to a Limey.’

‘And why exactly are you in Germany, Glenn?’ she asked her brother.

‘Dad told me that your husband knows Count Zeppelin. I was hoping he’d arrange an introduction for me.’

‘Count Zeppelin? Is he so famous that they’ve heard of him back home?’

‘They’ve sure heard of his airships,’ said Glenn. ‘Last September there was some kind of air show in Berlin….’

‘Yes,’ said Veronica. ‘Berliner Flugwoche at Johannisthal. There was a prize of one hundred and fifty thousand marks. Harald took the boys. They were there when an airplane flew from Tempelhof to Johannisthal: ten kilometres!’

‘Orville Wright was in Berlin at that time. And down in Frankfurt they had an airship meet: the Internationale Luftschiffahrt Ausstellung.’ He pronounced the German words with difficulty. ‘And suddenly a lot of people are taking a new interest in airships: especially big rigid airships. I want to see one of them, fly in one and find out what they’re like to handle.’

‘But surely you heard – the latest one, Deutschland, only lasted a couple of weeks. It’s a complete wreck. There were amazing pictures in the newspapers.’

‘Oh, sure LZ7: I know about that. But he still has the LZ6 flying, and a trip in that will suit me fine.’

Veronica turned to the Englishman. ‘And you, Mr Piper, do you share this obsession with flying machines that seems to be sweeping the world?’

‘Up to a point, Mrs Winter.’

‘He’s just being polite,’ said her brother. ‘I talked him into coming with me to see the zeps, because he can speak the lingo. I can’t speak German, and I don’t suppose Count von Zeppelin is going to be able to speak English.’

‘You’d better learn not to call him Count von Zeppelin: von Zeppelin or Count Zeppelin, but not both together.’

‘Is that so?’ said Glenn thoughtfully. ‘I know these Europeans get darn mad if you get their titles wrong. There was an Italian countess I once met in Mexico City. She wanted me to…’ He stopped, having suddenly decided not to go into detail.

Veronica laughed. She realized that the account of Glenn’s colourful experiences with horses, motorcars and canals had been carefully edited in order not to offend her.

‘And so you speak German, Mr Piper?’ she asked as the servants cleared the plates.

‘For my work I had to learn some Cape Dutch, Mrs Winter. It seemed foolish not to persevere with my German.’

‘He reads the kind of intellectual stuff you like, Veronica. I offered him my brand-new copy of Lord Jim when he was sitting alongside me on the promenade deck. And darn me if he didn’t wave it away. He said he doesn’t read Conrad because he doesn’t stretch the mind. I felt like punching him in the ear. That’s how we first got talking.’

Piper – even after his three months’ stay in America – had still not got used to this direct style of speaking. ‘I didn’t exactly say that, Glenn…’

‘He’s reading Das Stunden-Buch in German!’ added Glenn Rensselaer. ‘It took me half an hour to learn how to pronounce the title.’ Veronica noticed the mutual regard of the two men; somehow friendships between women didn’t flourish so easily and quickly.

‘I’m afraid that Rilke is too much for me,’ Piper admitted. ‘All that symbolic imagery requires a better knowledge of Germany and Germans.’

‘Oh, but it’s a wonderful book,’ said Veronica. ‘Don’t give up.’

‘I’ve tried so hard. The chapter I’m reading now: I’ve reread it, dictionary in hand, at least four times.’

‘Perhaps if we read a few pages together…’ Veronica stopped and hurriedly poured cream over the sliced peach. She hadn’t meant to say that…. She made her racing mind stop. She’d never looked at, not even thought of, another man in all the years she’d been married. When she first discovered that Harry had installed that very young girl Martha in an apartment in Vienna, she’d gone to pray in the Votivkirche, and so steal a glimpse at the street where his mistress was living. Yet, even in that hour of anguish, she had never thought of betraying him. But then she’d never met a man who might be able to tempt her to betrayal. Now, suddenly, she realized that.

‘That would be most civil of you, Mrs Winter,’ said the Englishman. ‘Sometimes it’s just a matter of understanding the heart of the author. Just a few pages properly understood might open a new world to me.’

‘I’m not a scholar,’ said Veronica. ‘I’m a thirty-five-year-old Hausfrau.’ It was her clumsy attempt to change direction.

‘I can’t let that go unchallenged,’ said Piper. ‘I cannot think of anyone in the world more likely to change my life.’

On the day that Father arrived, it rained without stopping. Not just the cold, thin drizzle through which the boys would walk, bathe in the ocean, or, in the happier days of the Valhalla, sail. It fell in great vertical sheets of water from slow-moving grey clouds that came from the North Sea to rain upon the bight.

While everyone prepared for Harald Winter’s arrival, the boys wandered through the house, getting in everyone’s way and feeling low. On previous days, Uncle Glenn or his English friend Mr Piper had kept them entertained with stories, tricks and card games. Pauli particularly liked Mr Piper’s magic and even learned to do some of the conjuring tricks himself. But today the two house-guests had gone to look at the wonderful old city of Lübeck and were not expected back until evening. By that time Father would have arrived.

Peter finally found something to do. Cook let him help prepare the vegetables. She needed the extra hand because the scullery maid was sick and the kitchen maid had been ordered away to ready the rooms on the second floor that Harald Winter and his wife used when both were there together.

After a brusque rejection by his grandmother, who wanted to sleep, Paul went in search of his mother. He found her in the turret room at the top of the house. It was a tiny circular room with a wonderful view of the countryside. This was where she liked to sleep when Father wasn’t with them. She was looking through her clothes in the wardrobe, taking her dresses out one by one and examining them before putting them on the bed for her maid to take to the other bedroom.

Paul stared at his mother. She did not look well. Her face was white but her eyes were reddened as if she’d been crying. ‘What is it?’ she said. She sounded angry.

‘Nothing,’ said little Pauli. ‘Can I help you, Mama?’

‘Not really, darling,’ she replied. Then, seeing Pauli’s disappointment, she said, ‘You can take my jewellery case downstairs. It will save Hanna a journey.’

Pauli always coveted his mother’s jewellery case. It was made of beautiful blue leather and lined with soft blue velvet. Inside, it was fitted with little drawers and soft pockets and velvet fingers upon which Mama’s rings were fitted. Pauli couldn’t resist playing with all the fittings of the box. It was such fun to pull out each drawer and see the sparkling diamond brooches or strings of pearls lying within. He looked at Mama, but she was completely occupied with her dresses – choosing one for Papa’s return, Pauli decided. He continued to play with the jewel box. Suppose it was a pirate ship and each drawer concealed a cannon, and as some unsuspecting boat came along … Oh dear: the contents of a drawer fell onto the carpet. How clumsy he was. He felt sure he would be scolded, but today it seemed as if nothing could divert her attention from her dresses.

Pauli picked up the tiny gold earrings, the large gold earrings, the pearl earrings, the diamond earrings that Mama wore only with her long dresses and pendant earrings. Two of each. He counted them again and then saw a silver earring on the carpet. Then there must be another …rolled under the bed, no doubt. He went flat on the floor to find it. Yes, there it was. And … there was something else there too. He pulled it out. A wristwatch. A large gold wristwatch with a seconds hand.

‘What are you doing, Pauli?’

‘I found a watch, Mama.’

‘What do you mean, Pauli?’