По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

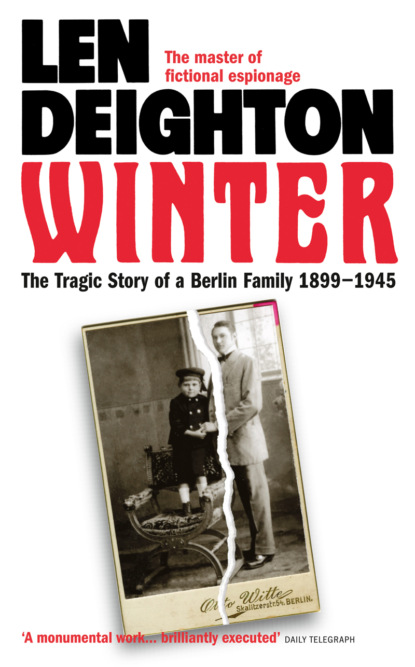

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Of course not, but if I’d known earlier, I could have had things better prepared. Those little rooms you have…’

‘The rooms are fine, sis, and I’m sorry we just descended on you. I didn’t realize how sick your mother-in-law is. It must make a lot of work for you.’

‘It’s good to see you, Glenn. Really good.’

‘Boy is stuck on you; you know that, don’t you?’ he blurted out. She had the feeling that he’d been trying to find a way of saying it ever since they’d first begun to talk.

‘Yes, I know he is.’

‘You get to know what a man’s like when you drink with him. And I’ve knocked around a bit, sis. I’ve met a lot of people since I last saw you. He’s a regular guy.’

She said nothing for a long time. He was her brother, and she felt she should respond. ‘He wants me to go away with him.’

‘Boy does?’ He was discomposed. He thought she’d just be flattered, and laugh. He wished he’d not mentioned it.

‘I don’t know what to do, Glenn. The children would never understand. Peter would feel I’d betrayed them, and Pauli just dotes on his father.’

‘Buck up, sis. It’s nothing to cry about.’

Glenn could not advise her; she’d known that before confiding in him. Glenn was her younger brother: their relationship precluded any chance that he could talk to her about such things and keep a sense of proportion. ‘Please don’t say anything to anyone, Glenn. I’m still trying to make up my mind. Boy wants me to bring the children, too.’

Glenn Rensselaer shook his head in amazement. ‘You’re a dark horse.’

‘I love him, Glenn. I don’t know how it happened in such a short time. I thought it was something that only happened in books and plays. But I love Harry, too.’ She turned her head away as the tears welled up in her eyes.

‘Divorced women are not received in our sort of society.’ He had to warn her. Glenn was a good man. He’d only wanted to make her happy, and now he found himself involved in her moral dilemma, the sort of thing he couldn’t handle.

‘I couldn’t go without the children, Glenn….’

‘It’s a big step.’ That bastard Harry, despite his philandering, would probably deny her a divorce: he detested the Englishman, Glenn could see that. So his sister would be living in sin in a society where such sinners were punished here on earth. The idea of that happening to his sister pained him. And yet Harry was a swine….

‘I couldn’t take Harry’s sons from him and give them to another man. That would be a sin, wouldn’t it?’ She wiped her tears away.

‘We only have one life. I’m not a priest.’

‘Hush! They’re coming in,’ said Veronica, catching sight of Piper and the two children coming up the path. As the doorman swung open the doors, the sound of a ship’s band playing on the sea front came to their ears. They were playing Sousa; such bold Yankee music sounded strange in these German surroundings.

Harald Winter’s final meeting with the representatives of the Imperial German Navy’s purchasing board had not left him in the best of moods. The meeting had ended with a gesture that Winter regarded as provocative. One of the civilians produced photographs of the army’s latest airship, the Parseval III, flying over Leipzig. Manufactured by Zeppelin’s brilliant rival, August von Parseval, it was a most efficient flying machine. It was big: its envelope contained five thousand cubic metres of gas. It had two hundred-horsepower engines and carried eight passengers. And yet the whole contraption could be deflated and taken away by horse-drawn wagon. This miracle was achieved by having no rigid metal framework. But the prospect of airships without a rigid metal framework had little or no attraction for Harald Winter. He left the meeting in a rage.

He snapped at the hotel staff and at his personal servants. When he was unlocking his decanters for a drink before dressing for dinner, he even found fault with the children.

‘They are getting out of control,’ he said.

‘How can you say that, Harry? Everyone remarks on how well behaved they are.’

‘They’re allowed to roam all through the hotel. And Pauli even pesters me when I’m working.’

‘And you snap at him. I wish you’d be more patient with little Pauli. He adores you so much, and yet you always reject him. Why?’

‘Pauli must grow up. He’s like a little puppy that comes licking your hand all the time. He wants constant attention.’

‘He wants affection.’ Harald Winter had never shown much affection to her or to the boys. He’d always said that earning money should be sufficient evidence of a man’s love for his family.

‘Then let him go to Nanny. What do I pay her for?’

‘Harry, how can you be so blind? Little Pauli loves you more than anyone in the whole world. You are his life. You hurt him deeply when you send him away with angry words.’ She didn’t want to pursue the subject. She tried to decide whether she could endure her corset as tight as this for the entire evening. Some women were abandoning corsets altogether – it was the new fashion – but Veronica still kept to the old styles.

Harald Winter poured brandy for himself and added a generous amount of Apollinaris soda water. He drank some and then turned his attention to the faults of their guests.

‘They act like a couple of spies,’ he complained. ‘Do you think no one notices them out on the promenade using their field glasses and making sketches of the warships?’

‘Spies?’ said Veronica. ‘You’re speaking of our guests; and one of them is my kith and kin.’

Harald Winter realized that he’d gone too far. He retracted a little. ‘I didn’t mean your brother, I meant the Engländer.’

‘No one was making sketches, Harry, and the field glasses belonged to Glenn.’

‘Piper is obviously a spy,’ said Winter. He had never really liked the English, and this fellow Piper, with his absurdly exaggerated good manners and the attention he gave to Veronica, was a prime example of the effete English upper class.

‘You sound like a character in those silly books the children read. If the ships are secret, why are they anchored here for everyone to see? And if you are convinced that Mr Piper is a spy, why bring him here?’

‘It’s better that he be someplace where the authorities can keep an eye on him,’ said Winter.

‘You didn’t repeat these suspicions to the people at Fleet Headquarters?’

‘I felt it was my duty.’ He put his glass down with more force than was necessary.

‘Harry, how could you! Mr Piper is our guest. To report him as a spy is…’

‘Ungentlemanly?’ asked Harry sarcastically. Nervously he smoothed his already well-brushed hair. A German wife would know better than to argue about such things.

‘No gentleman would do it, Harry,’ she told him. ‘No English gentleman would do it, and neither would a member of the Prussian Officer Corps. The officers to whom you reported your suspicions of Mr Piper will not see it as something to your credit, Harry.’ It was the first time she’d confronted him with such direct imputations. Harry’s already pale face became white with anger.

‘Damnit, Veronica. The fellow is sent to South Africa without any army rank. He learns to speak Afrikaans and wanders around anywhere that trouble arises. Then the fighting ends and, when you’d think Piper’s expertise is most needed, the British give him a year’s leave and he decides to go and look at zeppelins. But before that he turns up in Kiel, studying the most modern units of the Kaiser’s battle fleet through powerful field glasses.’

‘Must you Germans always be so suspicious?’ she said bitterly. ‘It was you who suggested bringing him to Kiel. You knew the Fleet would be here for the summer exercises – you told me that yourself. Then you report him for spying. Have you taken leave of your senses, Harry? Or are you just trying to find some perverse way to show these naval people how patriotic you can be?’

Her accusation hit him and took effect. His voice was icy cold, like his eyes. ‘If that’s the way you feel about us Germans, perhaps you’d be happier among your own people.’

‘Perhaps I would, Harry. Perhaps I would.’ She rang the bell for her bath to be run. She would be pleased to get back to her mother-in-law’s house. She didn’t like hotels.

Those final summer days at Travemünde marked a change in the children’s lives. They became both closer together and further apart. They were closer because both children knew that Pauli’s desperate leap overboard had saved his brother’s life. Both carried that certain knowledge with them always, and although it was seldom, if ever, referred to even obliquely, it influenced both of their lives.

They became further apart, too, for that summer marked the time when their carefree childhood really ended and they both, in different ways, faced the prospect of becoming men. Pauli, genial and anxious to please, did not relish the prospect of going to cadet school and becoming a member of the Prussian Officer Corps, and yet he accepted it, as he accepted everything his parents proposed, as the best possible course for someone of his rather limited abilities.

Peter’s ambition to be an explorer was, like so many of Peter’s ambitions, a way of describing his desire for freedom and independence. Peter was strong and respected strength, and his narrow escape from drowning made him see that strength came not only from intellect or muscles: strength could come from being in the right place at the right time. Sometimes strength could come from loving someone enough to jump into the sea. Peter had always considered his little brother weak, but now he wasn’t so sure.

The last two days at the house near Travemünde were filled with promises and farewells: false promises but sincere farewells. Glenn and his English friend were the first to go. When would the boys come and see Glenn in New York? Soon, very soon.