По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

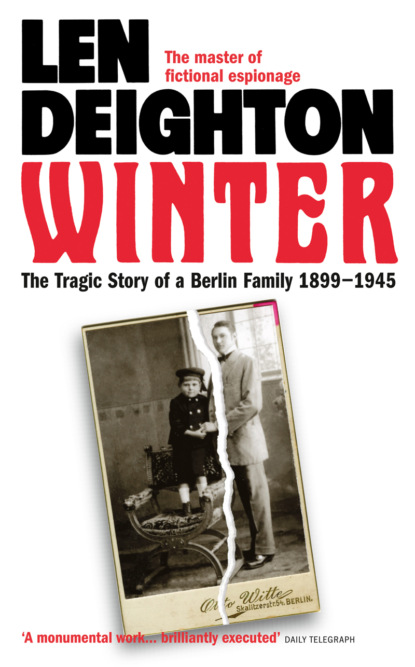

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The elderly American and his son were sitting in the library of the Travellers Club in London, drinking whiskey. They had the whole room to themselves. The club was quiet, as it always was at this time of the evening. Those members who had dined in were taking coffee downstairs, and the few theatregoers who dropped in for a nightcap had not arrived. Nowadays the risk of zeppelin raids persuaded most people to go home early. London – despite the presence of hordes of noisy, free-spending young officers – was not the town it had been before the war.

‘It sounds damned dangerous,’ said Cyrus G. Rensselaer. He was sixty-five years old but he looked younger. His hair was a little thinner and grey at the side, but the pale-blue eyes were clear and his waistline was trim. He felt as fit as ever. It was only looking at his thirty-six-year-old son that made him feel his age.

Glenn Rensselaer looked tired. ‘Sometimes it is dangerous,’ he agreed. ‘Most of them are only kids straight from school.’ For a year he’d been working as a civilian flying instructor for the Royal Flying Corps and lately he had been training pilots for night flying. It was a new skill and the casualty rate was alarming. ‘But the zeps come at night, so that’s when the British have to fly.’

‘Haven’t they got anti-aircraft guns?’

‘Not enough of them, and the Huns seem to know where the guns are. But the zeps are slow and planes can chase them. They are damned big and sometimes you can spot them better from up there.’ He looked at his father and saw that behind the sprightliness the old man was tired. ‘When did you get back from Switzerland, Dad?’

‘Yesterday afternoon. The train from Paris was packed with British officers, wounded mostly. Poor devils. Not many of them will fight again. I went to bed right away and slept the clock around.’

‘You’re in a hotel?’

‘The Savoy. It wasn’t worth opening the house for just a few nights. To tell you the truth, I’m thinking of selling it. If the war hadn’t brought property prices so low, I would have let it go last year, when you said you didn’t want to use it.’

‘The war must end soon, Dad. You’ll need a place in London.’ He wasn’t sure whether his father would still be young enough for the rigours of transatlantic crossing by the time these remorseless Europeans had fought themselves to a standstill, but he felt it was his duty always to encourage his hopes and plans. Cy Rensselaer’s wife, Mary, had died unexpectedly the previous year, and he didn’t want his father to go into what people called a decline.

But Glenn needn’t have worried about that. ‘Well, as a matter of fact I was going to have a word with you about family matters, son.’

‘Sure, Dad. What is it?’

‘Would you think I’m crazy if I told you I’m going to get hitched again?’

‘Hitched?’ For a moment he didn’t understand. ‘Hitched’ was not the sort of word that his father used. That he used it now was a measure of Cy Rensselaer’s embarrassment. ‘Married, you mean?’

‘Yes. Remarried. Is it too soon? I know you loved Mom.’

‘Whatever is best for you, Dad. You know that.’

‘Do you remember Dot Turner? Bob Turner’s widow.’

‘Turner Loans, Savings and Realty?’

‘She’s got three boys. A nice woman. I met her at a dinner party last Christmas and we get along just fine. Do I sound like an old fool, Glenn?’

‘No, Dad, of course not.’

‘I get lonely sometimes. I miss your mother. She did everything for me …It’s just the companionship.’

‘I know, Dad. I know.’

‘She wouldn’t take the place of your mother. No one could do that….’

‘It’s a great idea, Dad,’ said Glenn, still trying to get used to the prospect of having a new mother.

‘She’s too old to have a family or anything. It’s just companionship. She’s got all the money she needs, and her boys wouldn’t take the Rensselaer name. It wouldn’t make a jot of difference to you or Veronica.’

‘Sure, Dad, sure.’ He looked at his father and smiled. The old man leaned out and touched his son’s arm. He was happier now he’d got it off his chest.

‘And if you want the house here in London, I’ll turn it over to you.’

‘I live on the airfield. It’s comfortable enough out there. The Royal Flying Corps have even given me a servant – “batmen”, they call them. And I enjoy being with the youngsters. They are full of life and they talk nothing but flying. But tell me about Switzerland.’

‘I wanted to take the train and go right through to Berlin, and see dear Veronica,’ said the old man, ‘but the ambassador was so strongly against it.’

‘You must be careful, Dad. A lot of people would misunderstand a trip to meet a German partner.’

‘What do you mean, Glenn?’

‘Harald Winter is your partner, and he’s making aeroplanes and airships for the Germans. The British are in the middle of a desperate war. Your trip to meet Winter could be construed as a betrayal by your British friends.’

‘I wish to God I’d never loaned the money to him.’

‘But it’s been a good investment for you?’

His father’s voice was hoarse and hesitant. ‘He’s doing okay. He got into aviation at the very beginning, and he’s been very shrewd. He builds only under licence from other manufacturers so he doesn’t have all the worries about designing new ships and selling new ideas to the military.’

‘And Winter had no difficulties about meeting you in Switzerland? The British say that Germany is virtually under martial law.’

‘The Zeppelin company is in Friedrichshafen on the Bodensee. From there he had only a short trip on the ferryboat to Romanshorn. And Winter has become an important factor to the wartime economy; he’s a big shot now.’

‘I can imagine how he struts around.’

‘You never liked him, did you?’ said the old man. ‘I was always against him, too, but this time…’ He shrugged. ‘He looks really. worn out. I might have passed him on the street without recognizing him. And he’s really concerned about Veronica. I never realized how much she meant to him.’

‘Is he still running around with other women?’

‘How can I know that?’ said his father.

‘I wish she’d come home.’

‘We all wish she’d come home, Glenn. But it’s her life. We can’t live her life for her. And now that she’s ill, I have to say that Harald has done everything for her. She’s seen specialists in Berlin and Vienna, and she has a nurse night and day.’

‘I’ve never understood exactly what’s wrong with her.’

‘No one seems to know. The war came as a shock to her and now that Peter is serving with the Airship Division, she’s obviously worried about him. But it’s more complicated than that. Harald says she seems to have lost the will to live. It happens to some women, of course. Their children grow up and they find themselves beyond the age of childbearing. Somehow they feel useless.’

‘Especially if their husband spends all his spare time with his mistresses.’

‘We can’t be sure about that, Glenn.’

‘Men like him don’t change.’

‘We all change, Glenn. Some more than others, but we all change. Women have to feel needed, but maybe men have to feel needed, too. Maybe that’s why we all have this compulsion to go on working even when we have enough money to live in style.’

‘Poor Veronica.’

‘It’s pointless for her to worry about Peter. But that boy has a mind of his own. I remember how he went for me because I let slip a few home truths about Kaiser Bill. Even though he was just a child, he let fly at me. I was mad at him at the time, but when I thought about it I had to admire the little demon. It takes guts to challenge your grandfather in such circumstances. He’s a plucky kid. No surprise to me that he upped and joined the navy airships.’