По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

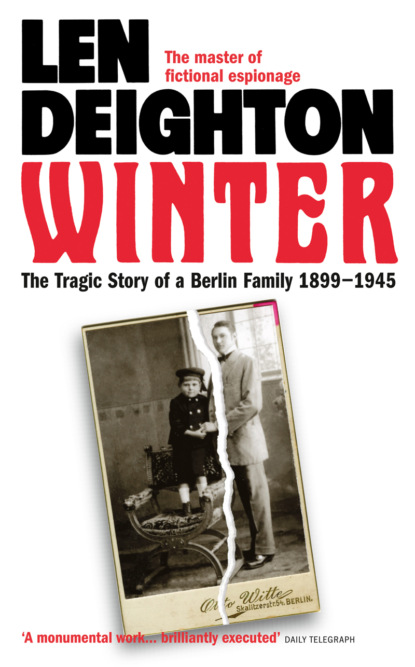

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Prepare for action! Open bomb doors!’ He noted the exact time: 2304 hours. At first he was going to advise dropping bombs on the Houses of Parliament, but the briefing clearly said railway stations. There were two right below: Waterloo and Charing Cross. Peter signalled and the captain ordered the first lot of bombs released. There was a series of flashes as they hit, and though Peter could imagine the terror and destruction they had brought, he had no deep feeling of remorse or regret. The British had had every chance to stay out of the war, but they had decided to interfere, and now they must face the consequences.

Crash! The second lot of bombs were striking somewhere south of the river. It was mostly just workers’ housing on that side of the water. The captain should have awaited Peter’s signal, but everyone got excited. There were more explosions, though without any corresponding lights on the ground. He suddenly realized that it was the sound of the British anti-aircraft guns. They were very close, and for the first time on such a war flight Peter felt a little afraid.

At least there were no searchlights here in the very heart of town. The British had concentrated their searchlights to the northeast and along the approaches. They could be seen there now, steadily moving in search of the zeppelins that were behind them. Wait: they were clustering together. They’d caught someone. Two more anti-aircraft shells exploded very close. In the gondola Peter heard the captain order the firing of a red Very pistol light. It was a trick – pretending to be a British fighter plane ordering the guns silent – but the ‘colour of the night’ was changed sometimes hour by hour, and the gunners were not often tricked. The light went arcing out into the darkness, a red firework sinking slowly.

‘Drop water ballast forward!’ murmured the captain, and immediately the orders were given. Peter hung on tight, knowing that the airship would tilt upwards to an alarming angle as she began to rise. There was the whoosh of water rushing through the traps. There she went! The gunfire explosions dropped away below them like the repeated sparking of a cigarette lighter that would not ignite. They continued to rise. Here in the upper air it was dark and cold.

By now a dozen searchlights had fastened on the airship behind them to the north. ‘The Dragon!’ said a whispered voice in the gondola. How could it be the Dragon? She’d been ahead of them. Of course, she was always very slow. Those old engines of hers were the subject of endless grim jokes. They’d been promised new engines again and again, but all the new engines were needed for new airships.

The telephone rang and was answered by Hildmann. ‘Number-two gun position report enemy aircraft,’ he said.

‘Switch off engines!’

The silence came as a sudden shock after so many hours with the throbbing sound of the engines. Everyone throughout the airship remained as quiet as possible and listened.

It was Peter, staring down to the townscape below who spotted him, a large biplane climbing in a wide circle trying to get into position for an attack. The fighters liked to rake the airships from stern to nose, using the new explosive and incendiary bullets. ‘Fighter!’ He pointed.

The captain bit his lip and turned his head to see the instruments. The airship was still at the slightly nose-up angle that provided extra dynamic lift.

Suddenly all was grey: the sky, the ground and all the windows. The zeppelin had passed up into a patch of cloud. Now, with all speed, the airship was ‘weighed off’. The upward movement ended and the airship stopped, engines off and completely silent, shrouded in the grey wet cloud. The mist around them brightened as the searchlight beams raked the cloud’s underside and made the water vapour glow.

They could hear the aeroplane now. It had followed them into the cloud and passed near on the starboard side, its engine faltering as the dampness of the cloud affected the carburettor. It circled once, as if the fighter pilot knew where they were hiding, and then, after another, wider circle, the sound of the plane’s engine grew fainter.

‘Restart engines!’ The clutches were engaged till the props were just turning, treading the air so that the airship scarcely moved. They waited five minutes or more before dropping more water ballast and recommencing their upward movement. Suddenly they were out of the cloud and the stars were overhead. They were very high now and could see a long way. Over northern London clusters of searchlights were still moving slowly across the sky, searching for the airships heading back that way.

Peter provided a course to steer, and slowly – the engines weakened on this thinner air – they headed for home. Everyone was watching the horizon, where the English defences were concentrated. Every few minutes there was a flicker of gunfire, like fireflies on a summer’s evening. That was the gauntlet that they must also run.

‘Look there!’

One by one the searchlights swung over to one point in the sky, forming a pyramid with a silvery shape at its tip. Then the silvery shape went red. At first the red glow was scarcely brighter than the searchlight beams below it. Then it went to a much lighter red, as a cigar tip brightens at a sudden intake of breath.

‘My God!’ Even the captain was moved to cry out aloud. Everyone stared. Flight discipline, rank, was for a moment forgotten. All stared at the terrible sight. None of them had seen such a thing before, except in their nightmares. The stricken airship flared white like a torch, so bright that it blinded them, and they were unable properly to see the dull-red sun into which it changed before dropping earthwards. Then the fiery tangle vanished into a cloud, and the cloud turned pink and boiled like a great furnace.

It was in the silence that followed that the telephone rang. The observation officer – Hildmann – answered tersely. He looked round the control gondola and stared at Peter. If there was a job, then Peter was the one likely to be spared from duties here in the car. The course home was set, and the charts were already folded away, the pencils in their leather case in the rack over the plotting table.

So it was Peter who was sent to speak with the sailmaker. The gas bags were holed; the captain must know how badly. Was it the small punctures that the scout’s machine guns made, or the far more serious jagged tears from shell fragments? Were the leaks low down, or were they in the upper sections of the bags, where a leak meant the loss of all the gas it held? Peter looked around to find an extra scarf and the sheepskin gloves that he’d removed to use the pencils. It would be cold back there inside the envelope, even colder than it was here in the drafty control gondola. He’d found only one glove by the time Hildmann shouted to him again. No matter: he’d keep his hand in his pocket.

He went up the ladder again. It was dark and dangerous picking his way along the keel between the lines of gas bags. It was like walking down the aisle of some echoing cathedral, except that huge silky balloons floated inside and filled the whole nave, from floor to vaulting.

Some of the giant bags were hanging soft and empty. It was here that the sailmaker was already at work, patching the leaks. He called down from the darkness: ‘Herr Leutnant.’ The sailmaker was clinging to the girders high above him. Peter climbed with difficulty. The lack of oxygen made him feel dizzy.

It was while Peter was inspecting the damaged gas bags that the anti-aircraft battery scored its hit. There was a loud bang that echoed in the framework. The airship careened, remained for a moment on its side, so that everything tilted and the half-emptied bags enveloped the two men. Peter fought the silky fabric aside as the airship rolled slowly back and then steadied again. ‘What the devil was that?’ said the sailmaker. Peter didn’t reply, but he knew they were hit and hit badly. It was a miracle that there was no fire. ‘Stay here,’ said Peter. ‘I’ll find out what’s happened.’

When he got back to the control gondola, it was in ruins. The rear portion of the car was gone completely, and a large section of the thin metal floor was missing, so that, still standing on the short communication ladder to the keel, Peter could see the landscape thousands of feet below them. The helmsman and rudder man were nowhere to be seen: the explosion had blown them out into the thin air.

There was broken window celluloid everywhere, and the aluminium girders were bent into curious shapes, like the tendrils of some exotic vine. The body of the captain – hatless to reveal an almost bald head – was sprawled on the floor in the corner, his head slumped on his chest. The observation officer had survived, of course: Hildmann was a tough old bird, the sort of man who always survived. He had somehow scrambled across the two remaining girders and got to the front of the car. He was manning the elevator wheel. When he saw Peter coming down through the hatch, he pointed to the wheel that controlled the rudders and then went back to his task.

‘How bad?’ Hildmann asked him after Peter had swung himself across the gaping hole to take his place at the wheel and steer for home.

‘The gas bags? Two of them are bad, and some of the holes are high. But the sailmaker is a good man, and his assistant is at work, too.’

The observation officer grunted. ‘We can let it go lower, much lower.’ His voice was strained as he gasped for breath. Hildmann was no longer young. At this height the lack of oxygen caused dizziness and headaches and every little exertion seemed exhausting. Peter’s clamber down into the car had made his ears ring, and his pulse was beating at almost twice its normal rate. In the engine cars, and up on the gun positions, men would be suffering nausea and vomiting. It was worth going high to avoid the defences, but today they hadn’t avoided them. ‘A lucky shot,’ said Hildmann, as if reading Peter’s mind.

‘There will be more guns along the coast,’ warned Peter.

‘We must risk that. The gas will be escaping fast at this height; soon we’ll lose altitude whether we want to or not. And the engines will give us more power lower down.’

Peter didn’t answer. Hildmann was deluding himself. The pressure inside the bags would make little difference. Whatever they decided, the airship was continuing to sink, due to the lost hydrogen from the punctured gas cells. Peter was having great difficulty at the helm of the great ship. He had never touched the wheel before; the seamen given this job were carefully chosen and specially trained. Holding the brute, as it wilfully tried to fly its own course through the open sky, was a far harder task than he ever would have believed. He had new respect for the men he’d watched doing it so calmly and effortlessly. And as the thought came to him, he realized that now he would never be able to tell them so: both men had long since hit the ground at terminal velocity, which meant enough force to indent themselves deep into the earth.

‘Is he patching the holes?’ said Hildmann.

‘The sailmaker and his assistant,’ affirmed Peter. ‘They can’t work miracles, though.’

In other circumstances Hildmann might have considered Peter’s reply insubordinate, but now he seemed not to notice the apparent disrespect.

‘We’re sinking still,’ said Hildmann, at last facing the reality of their danger. ‘They’d better work fast.’ The airship dropped lower and lower until the altimeter – an unreliable device worked by barometric pressure – warned them they were as low as they dared go in darkness. Then it became a battle to stay in the air. In other parts of the airship, crewmen, on their own initiative, began to throw overboard everything that could be spared. Desperately men dumped the reserve fuel, ammunition boxes, then ammunition; finally, as they crossed the coast near Yarmouth, the guns went, too.

‘Can you work the radio?’ asked Hildmann.

‘I can try, Herr Oberleutnant.’ The radio looked to be in bad shape, the glass dials shattered and a fresh bright-silver gash across its metal case. There was little or no chance that it would still be working. The clock over it had stopped, a mute record of the exact moment the shell burst struck.

‘We’ll probably come down in the sea. We need to know the position of the nearest ship.’

And find it, thought Peter. He had only the haziest idea of their present position, and finding such a dot in the North Sea would need a navigational skill far beyond his own crude vectors and sums. But for a moment he was spared such tests; there was no question of his leaving the helm until a relief could be summoned, and the telephone link was severed.

‘Better not look down,’ said Hildmann in a voice that was almost avuncular.

Had the old man just discovered that, thought Peter. The void beyond the gap in the car’s floor was the most terrifying sight he’d ever seen. After that first shock he’d kept his eyes away from the jagged hole.

‘Jawohl, Herr Oberleutnant!’

‘You’re a good, reliable officer, Winter.’

‘Thank you, Herr Oberleutnant,’ said Peter but he wished the observation officer hadn’t said it. It was too much like an epitaph. He had the feeling that Hildmann had said it only because their chances of survival were so slim. It would be just like him to be writing their final report in his head before going to meet his Maker.

‘Request the Oberleutnant’s permission to change course five degrees southwards.’

‘Why?’ asked Hildmann.

‘The compass must be wrong. Dawn is coming up.’

The observation officer stared at where the horizon would be if the night had not been so very dark. Then he saw what Peter had been looking at for five minutes: a dull-red cotton thread on the silky blackness of the night. Hildmann looked at his watch to see whether the sun was on schedule. ‘Yes, change course,’ he said, having decided that it was.

The dawn came quickly, changing the sky to orange and then a sulphurous yellow before lighting the grey sea beneath them. Crosslit, the choppy water was not a reassuring sight.

‘Is that the coast ahead?’

‘Yes, Herr Oberleutnant.’