По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

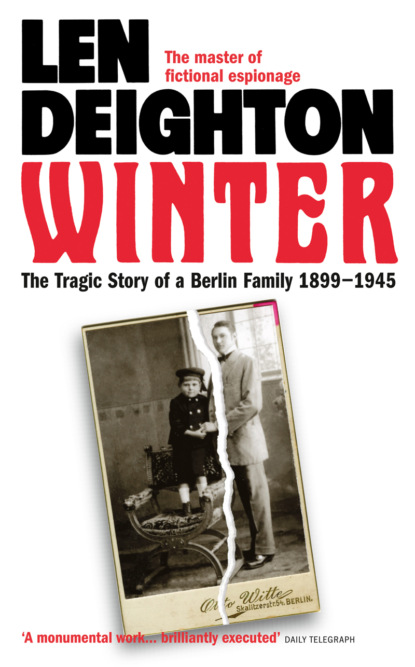

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Won’t need the radio now.’

‘No, Herr Oberleutnant.’

‘Just as well. I don’t think it’s working.’

‘I don’t think it is, Herr Oberleutnant.’

‘Do you think we’ll be able to get it down in the right place?’

‘I think we can, Herr Oberleutnant.’ Hildmann would have been outraged by any other response, but he smiled grimly and nodded. Peter wondered how old he was; rumours said he was a grandfather.

‘We lost the Dragon.’

‘Yes, Herr Oberleutnant.’ Trees appeared behind the desolate sandy coastline. They were very low. He stared down into the darkness.

‘Good men on the Dragon.’

‘Yes, Herr Oberleutnant.’

‘Oh my God!’

Everything happened so suddenly that there was no time to avert the crash. The elevator cables had been in shreds for hours. Hildmann didn’t realize that the movements of his wheel depended upon a single steel thread until the final thread snapped and the elevators slammed over to put the airship into a violent nose-down attitude. It all happened in only a few seconds.

First there was the sudden snapping of the control cables: bangs like explosions came as the released steel cables thrashed about, ripping through the gas bags and tearing into the soft aluminium. The lurch started Hildmann’s wheel spinning and sent Hildmann staggering across the car so that he stumbled and was thrown half out of the hole in the floor. Then came the big crash of the airship striking the tree tops.

Branches came into the car from every side, and a snowstorm of leaves and wood and sawdust filled the control room, until the weakened gondola was torn into pieces by the black trees. There was a scream as Hildmann disappeared into the darkness below, and then the airship met a tree that would not yield, and, with a crash and the shriek of tortured metal, the vast framework collapsed upon him and Peter lost consciousness.

‘My poor Harry’

In Vienna that same September morning it was bright and clear. The low-pressure region that had provided the zeppelins with cloud cover over England had broken. Southern Germany and Austria had blue skies and cold winds.

Martha Somló – or Frau Winter, as she had engraved on her visiting cards – was awake. She’d been an early riser ever since she was a child, when she’d got up at five every morning to prepare the work in her father’s back-room tailor shop.

Harald Winter was sound asleep. He snorted and turned over. ‘Wake up! Harry.’ She had a tray with coffee and warm fresh bread.

He grunted.

‘Wake up! You were snoring.’

He rubbed his face to bring himself awake. ‘Snoring?’

‘Yes. Loud enough to wake the street.’ She smiled sweetly and forgivingly.

He looked at her suspiciously. Veronica had never mentioned his snoring, nor had any of the other women he enjoyed on a more-or-less regular basis. ‘It’s an ugly habit, snoring,’ he said.

He opened his eyes to see her better. She was wearing the magnificent silk dressing gown he’d bought for her on one of his trips to Switzerland. It was black and gold, with huge Chinese tigers leaping across it. He’d thought at the time how like Martha the snarling tigers looked. ‘It doesn’t matter, darling. You can’t help it,’ she said.

The truth was that Harald Winter did not snore, but teasing him was one of the few retaliations she got for being neglected.

She set the tray down on the bed and slid back under the bedclothes. This was her very favourite time: just her and Harry at breakfast. He gave her a quick hug and kiss before taking a kaiser roll and waiting for her to pour his coffee and add exactly the amount of cream and sugar he liked. From the street below came the sound of horses’ hoofs and wheels upon the cobbles and the jingle of harness. It was a large contingent of field artillery moving off to the war. The noise continued for a long time, but neither Harry nor Martha went to the window to look. Soldiers had become too common a sight in the streets of Vienna for breakfast to be interrupted.

Prompted by the sounds of the horse artillery, Martha said, ‘The war’s going badly for us, isn’t it, Harry?’ She removed the tray to the side table and came back to bed.

‘It goes up and down: wars are always like that.’

‘And you don’t care, as long as you sell your airships and planes, and make lots of money.’

‘My God, but you are a little firebrand, aren’t you?’

He grabbed her wrist and clutched it tight. It hurt, but she wouldn’t give him the satisfaction of complaining. In fact, his physical strength attracted her even when it was directed against her. In the same way, her strong-willed antagonism fascinated him. She was the only woman who openly defied him.

‘I heard there were wooden airships now,’ she said spitefully, ‘and smaller, collapsible ones better than Count Zeppelin makes.’

He smiled. ‘I have persuaded the navy that airships made of wood and glue are not suitable for use over the sea in bad weather.’

‘You think only of money!’ she said.

He released her arm and said softly, ‘How can you say that, you little bitch, when I have two sons fighting for us?’

‘I’m sorry, Harry. I didn’t mean it.’

He gently pulled the silk negligee from her shoulders so that he could look at her pale body. ‘You are exquisite, darling Martha. All is forgiven in your embrace.’ It was the frivolous, supercilious manner he adopted for their bouts of lovemaking. It was a way of avoiding any serious discussion.

But as he reached for her there was a knock at the bedroom door. Martha twisted away from his hand and, pulling her dressing gown tight, went to the door.

It was her maidservant. He couldn’t hear what was said. Despite reassurances from his physician, he was convinced that he was growing deaf.

‘What is it?’ he said as she returned to the bed. ‘Come back to bed, my little tiger.’ But she remained where she was, a petite, pale figure, her face forlorn, with jet-black hair tumbling over her eyes till she pushed it back with her small, perfect hands.

‘The zeppelins over England last night…five didn’t return. Your son Peter…’ She couldn’t go on. Tears filled her eyes.

‘My Peter…What?’ He got out of bed, and went to her and held her. She was sobbing. ‘My poor Harry,’ she said.

It was almost noon next day when Peter started to regain his senses. Even before he tried to open his eyes, he smelled the ether in his nostrils. The hospital room was filled with yellow light: the sun coming through a lowered blind. When he moved his feet – an exploratory movement to discover if he was all in one piece – he felt the stiffly starched sheets against his toes. It was only then that he realized he was not alone in the hospital room. Two men in white coats were standing near the window, looking down at a clipboard.

‘…the only one to escape from the forward gondola,’ said one voice.

‘And completely unharmed, you say?’

‘Just scratches, bruises, and the finger.’

‘Did he lose the finger?’

‘No, he had the luck of the devil. I just removed the tip of it.’

‘And it was the left hand, too; well, I can’t imagine that that will make a scrap of difference to any young chap.’

‘Unless he was a pianist…’