По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

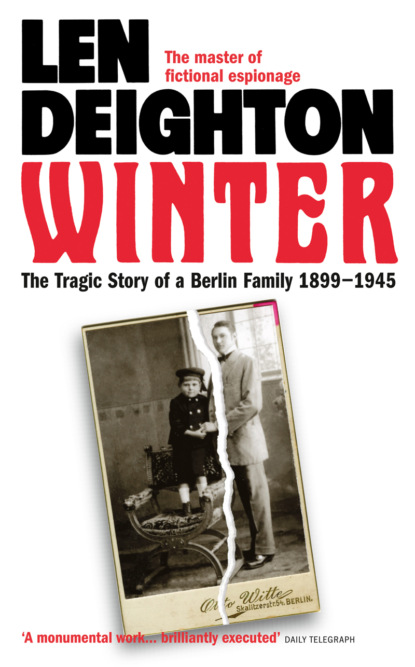

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Achtung! Stand clear of propellers!’ the duty officer in charge of the ground crew shouted. The engineers let in the clutches and engaged the gears. One by one the big Maybach engines took the weight of the four-bladed wooden props and the engines modulated to a lower note. A cloud of dust was kicked up from the floor of the shed.

Peter swung aboard and almost collided with men loading the bombs: four thousand pounds of high explosive and incendiaries. As he stepped aboard, the airship swayed and one of the handling party unhooked a sack of ballast from the side of the airship. Its weight approximated that of Peter so that the airship continued in its state of equilibrium within the shed.

He climbed into the control gondola, a tiny glass-sided room two yards wide and three yards long. The others were already in position, and there was little space to spare. Above the roar of the engines came the constant jingle of the engine room telegraph and the buzz of the telephones. The noise lessened as the engineers throttled back until the engines were just ticking over. Then they were switched off and it became unnaturally quiet.

The captain – a thirty-three-year-old Kapitänleutnant – nodded in response to Peter’s salute, but the rudder man and the man at the elevator did not look up. Hildmann, the observation officer – a veteran with goatee beard – immediately said, ‘Winter, go and take another look at the windsock. This damned wind is changing all the time…. No, it’s all right. Carl is doing it.’ And then, to the captain, he said, ‘All clear for leaving the shed.’ The observation officer then climbed down from the gondola in order to supervise the tricky task of walking the airship out of the shed.

There was the sound of whistles, and the command ‘Airship march!’ as the ground handling party tugged at the ropes and heaved at the handles on the fore and aft gondolas to run the airship out through the narrow shed door. Peter leaned out of the gondola and watched anxiously. The previous month, in just such a situation, the airship had brushed the doorway and suffered enough damage to be kept grounded. For that mistake their leave had been cancelled, and leave these days was precious to everyone. When the stern came out of the shed there was a murmur of relief.

‘Slip astern!’ The rearmost ropes were cast off, and she began to swing round so rapidly that the men of the handling party had to run to keep up with her. Then, with all the ground crew tugging at her, the airship stopped. Hildmann climbed back aboard and, with a quick look round, the captain gave the order to restart engines. In response to the ringing of the telegraphs, one after another the warmed engines roared into life. ‘Up!’ The handling party let go of the leading gondola and she reared up at an angle.

‘Stern engines full speed ahead!’

Now the handling party holding the handles along the rear gondola could not have held on to it without being pulled aloft. Suddenly the ship was airborne and every man aboard felt the deck swing free underfoot, and the airship wallowed in the warm afternoon air. It would be many hours before they’d feel solid ground underfoot.

The engineer officer saluted the captain before climbing the ladder from the control room up to the keel. His fur-lined boots disappeared through the dark rectangle in the ceiling. He was off to his position at the rear-engine gondola. He would spend the rest of the flight with his engines. The other men moved to take advantage of the extra space.

Now that the airship was well clear of the roofs of the sheds, the motors were revved up to full speed. There was no real hurry to reach the rendezvous spot in the cold air of the North Sea, but when so many zeppelins were flying together, it always became something of a race.

There were twenty-three in the crew. They knew one another very well by now. Apart from two of the engine mechanics and the sailmaker – whose job it was to repair leaks in the gas bags or outer envelope – they’d all trained and served together for some ten months. They’d flown out of Leipzig learning their airmanship on the old passenger zeppelins, including the famous Viktoria-Luise. They were happy days. But that was a long time ago. Now the war seemed to be a grim contest of endurance.

Oberleutnant Hildmann, the observation officer – who was also second in command – was a martinet who’d served many years with the Baltic Fleet. It was he who had assigned Peter to navigation. Actually this was the steersman’s job, but Peter’s effortless mental arithmetic gave him a great advantage when it came to working out endless triangles of velocity. It was a skill worth having when Headquarters radioed so many different wind speeds, and in the black night they tried to estimate their position over the darkened enemy landscape.

Peter had been given a sheltered corner of the chilly, windswept control gondola in which to spread his navigation charts. Now he scribbled the airship’s course and her estimated speed on a piece of paper, and tried to catch glimpses of the North German coast. Upon the map he would then draw a triangle, and from this get an idea of what winds the night would bring.

There was cumulus cloud to the north and a scattering of cirrus. The forecast said that there would be scattered clouds over eastern England by evening. That was good news: cloud provided a place to hide.

When they reached Norderney – a small island in the North Sea used as a navigation pinpoint – Peter spotted several other zeppelins. The sun shone brightly on their silver fabric. One of them, well to the rear, was easily recognized as the Dragon: her engines were worn out with so many war flights over these waters, so that her mechanics had to nurse the noisy machinery all the way. Nearer was the L23, with another naval airship moving through the mist beyond. It was a big raid today. Rumours said that there were a dozen naval airships engaged, and three or four army airships, too. Perhaps this would be the raid that would convince the British to seek peace terms. The newspapers all said that the British were reeling under the air raids on London, and the foolhardy British offensive along the river Somme in July had been a bloodletting for them.

For Peter, London was just a dim memory. It seemed a long time ago since he had last visited his grandparents in the big house there. He remembered his grandfather and the big English fruitcakes that were served at four o’clock each day. He remembered the busy streets in the City, where Grandfather had an office, and the quiet gardens and the street musicians to whom Grandfather always gave money. Especially vividly he recalled the piper, a Highlander in kilt and full Scots costume. He seemed too haughty to ask for money, but he stooped to pick up the coins thrown from the nursery window. The piper always came by about teatime, and the little German band came soon after. The bandleader was a big fellow with a red face and furious arm movements. He was astonished when Pauli responded to their music with rough and rude Berlin slang.

Peter’s memories of London had no meaning for him now. His boyhood desire to become an explorer was almost forgotten. The war had changed him. He’d lost too many comrades to relish these bombing missions. He was proud of his active, dangerous role, but when victory came he’d be content to spend the rest of his life in Berlin.

The whistle on the speaking tube sounded. Peter took the whistle from the tube, which he then put to his ear: ‘Hello?’ It was the lookout reporting the sighting of a ship: a German destroyer heading for Bremen. Peter noted it in the log and went back to his charts. They were at the rendezvous. Now commenced the worst part of the mission. Here at the rendezvous there would be hours of waiting, the engines ticking over just enough to hold position in the air. A skeleton crew on duty and anything up to a dozen men in hammocks slung along the gangways. No one would sleep; no one ever slept. You just stretched out and wondered what the night would bring. You remembered the stories about the airships that had broken up in mid-air or burst into flames. You wondered if the British had improved upon their anti-aircraft gunfire or perfected the incendiary bullets that the fighter planes fired.

The whitecapped sea would soon darken. But the days were long up here in the sky. Although the sun sank lower and lower, the waiting airships remained bathed in its light, glowing with that golden luminosity that is so like flame.

‘Winter. Leave whatever you’re doing and go to the number-two gun position: the telephone is not working.’

The observation officer was not a bad fellow, but he, too, succumbed to the nervousness of these waiting periods. Peter knew that there was nothing wrong with the telephone. The gunners were down inside the hull, out of the cold airstream, trying to keep warm. Once you got cold there was no way to get warm again: there was no such thing as a warm place on a naval airship. And who could blame the gun crew? There was no chance of enemy aircraft out here, so far from the English coast.

‘Ja, Herr Oberleutnant. Right away,’ Peter saluted him. Saluting was not insisted on in such circumstances, but Hildmann, like most regular officers of the old navy, didn’t like the ‘sloppy informality’ of the Airship Division.

Peter climbed the short ladder that connected the control gondola to the keel. To get to the upper gun position took Peter right through the airship’s hull. As he walked along the narrow gangway, he looked down through the gaps in the flapping outer cover and could see the ocean, almost three thousand feet below. The water was grey and spumy, speckled with the last low rays of sunlight coming through the broken cloud. Peter didn’t look down except when he had to. The ocean was a threatening sight. He had never enjoyed sailing since that day when he’d nearly drowned, and the prospect of serving on a surface vessel filled him with horror.

Some light was reflected from below, but the inside of the airship was dark. Above him the huge gas cells moved constantly. All around him there were noises: it was like being in the bowels of some huge monster. Besides the rustling of the gas cells there was the creaking of the aluminium framework along which he walked and the musical cries of thousands of steel bracing wires.

It was a fearsomely long vertical ladder that took him up between the gas cells to the very top of the envelope. Finally he emerged into the daylight on the top of the zeppelin. Suddenly it was very sunny, but the air was bitterly cold and he had to hold tight to the safety rail. What a curious place it was up here on the upper side of the hull. The silver fabric sloped away to each side, and the great length of the airship was emphasized. What an amazing achievement it was for man to build a flying machine as big as a cathedral.

Peter stood there staring for a moment or two. To the port-side he could see two other zeppelins. They were higher, by several hundred feet. Ahead was a flicker of light reflected off another airship’s fabric. That would be the old Dragon fighting to gain height. She’d caught up with the armada. It was good to see her so close; Peter had friends aboard her. They were not alone here in the upper air.

It was late afternoon. Still the airships glowed with sunlight. Soon, as the sun sank lower, the airships would darken one by one, darken like lights being extinguished. Then, when even the highest one went dark, they would move off towards England. Peter shivered; it was cold up here, very cold.

‘Hennig!’ called Peter loudly. He knew where the fellow would be hiding: all the gunners took shelter, but Hennig was the laziest.

‘What’s wrong, Herr Leutnant?’ He emerged blinking into the light and behind him came the loader, a diminutive youth named Stein, who followed the gunner everywhere. Stein was a Bolshevik agitator, though so far he’d been too sly to be caught spreading sedition amongst the seamen. Still, his cunning hadn’t saved him from several nasty beatings from fellow sailors who opposed his political views. Hennig was not thought to be a Bolshevik, but the two men were individualistic to the point of eccentricity, and neither would be welcomed into other gun teams. So they had formed an alliance, a pact of mutual assistance. Erich Hennig pushed his assistant gently aside. It was a gesture that said that if there was any blame to be taken he would take it. ‘What’s wrong, Leutnant?’ he said again. Hennig was a slim, pale youth of about Peter’s age. His dark eyes were heavy-lidded, his lips thin and bloodless.

‘You should be at the gun, Hennig.’

‘Ja, Herr Leutnant.’ Hennig smiled. It was a provocative and superior smile, the smile a man gave to show himself and others that he was not subject to authority. It was a smile for Peter Winter alone: the two men knew each other well. Winter had known Hennig since long before both men volunteered for the navy. Erich Hennig lived in Wedding; his father was a skilled cooper who worked in the docks mending damaged barrels. The apartment in which he grew up, with half a dozen brothers and sisters, was cramped and gloomy. At school Hennig proved below average at lessons, but he earned money by playing the piano in Bierwirtschaften – stand-up bars – and seedy clubs. It was a club owner who brought Erich Hennig’s talent to the attention of the amazing Frau Wisliceny. And through her efforts Hennig spent three years studying composition and theory at the conservatoire. By the time war broke out, Erich Hennig was being spoken of as a talent to watch. In April 1914 he’d given a series of recitals – mostly Chopin and Brahms – at a small concert hall near the Eden Hotel. There was even a paragraph about it in the newspaper: ‘promising,’ said the music critic.

Peter had met Hennig frequently at Frau Wisliceny’s house. Once they’d even played duets, but no friendship ever developed between them. Hennig was fiercely competitive. He saw the privileged Peter Winter as a spoiled dilettante who lacked the passionate love for music that Hennig knew. He’d actually heard Peter Winter discussing with the Wisliceny daughters whether he should pursue a career in music, study higher mathematics, or just prepare himself for a job alongside his father. This enraged Hennig. For Hennig it was a betrayal of talent. How could any talented musician – and even Erich Hennig admitted to himself, if not to others, that Peter Winter was no less talented than himself – speak of any other career?

‘When the telephone rings, you make sure you answer it,’ said Peter.

‘I do, Herr Leutnant.’ He continued leaning against the gun.

‘You should be standing to attention, Hennig.’

‘I’m manning the gun, Herr Leutnant.’

The wretch always had an answer ready. And Peter well knew that any complaint about Hennig would not be welcome. Hennig played piano in the officers’ mess. He could be an engaging young man when he tried, and he had a lot of supporters amongst the senior ranks. When the beer and wine were flowing and the old songs were sung until the small hours of the morning, Hennig became a sort of unofficial member of the officers’ club. It would be a foolish young officer who punished him for what might sound like no reason but jealousy. For Peter would never be able to play the sort of music that got a party going. In this respect he admired Hennig’s talent and envied those years that Hennig had spent strumming untuned pianos for drunken clubgoers. Hennig always found under his fingertips the right melodies for the right moments. And he remembered them. He knew the tune the Kapitänleutnant had danced to the night he met his wife. He knew those bits of Strauss that the observation officer could hum. He knew when the captain might be induced to sing his inimitable tuneless version of ‘I’m Going to Maxim’s’ and changed key to help him; and he knew the hymn tunes for which there were words that could be sung only after the captain departed.

Peter Winter’s musical talent was the talent of the mathematician, and, as was the case with most mathematicians, Bach was his first musical choice. Peter’s love for Bach was a reflection of his upbringing, his social class, and the time and place in which he lived. There was a measured orderliness and formality to Bach’s music: a promise of permanence that most Europeans took for granted. Playing Bach, Peter displayed a skill and devotion that Hennig could never equal. But Hennig never played Bach. And Peter never played the piano in the officers’ mess, where Bach was not revered.

Peter went to the telephone, swung the handle round until the control gondola answered. ‘Upper gun position. Testing,’ said Peter.

‘Your voice is loud and clear, Herr Leutnant,’ said the petty-officer signalman.

Peter replaced the earpiece. ‘Carry on, Hennig,’ he said.

‘I will, Herr Leutnant,’ said Hennig. And as Peter started on the long and treacherous vertical ladder, he heard the loader titter. He decided it was better not to hear it.

As he picked his way back down the ladder to the keel, he thought about his exchange with Hennig. He knew he’d come out of it badly. He always came out of such exchanges badly. He didn’t have the right temperament to deal with the Hennigs of this world. He had tried, God knows he’d tried. Early in their first training flights, on one of the old Hansa passenger zeppelins, he’d talked to Hennig and suggested he apply for officer training. Hennig had taken it as some subtle sort of insult and had rejected the idea with contempt.

But in the forefront of Peter’s mind was the fact that Hennig had lately become more than friendly with Lisl Wisliceny, whom Peter considered his girl. Particularly hurtful was the latest letter from Lisl. Until now she’d been pressing Peter to become engaged to her. Peter, reluctant to face the sort of scene that his father would make in such circumstances, had found excuses. But in her latest letter Lisl had written that she now agreed with Peter, that they were both too young to think of marriage, and that she should see more people while Peter was away. And by ‘people’ she meant Erich Hennig. That much Peter was certain about. Only after Peter had taken Lisl to the opera did young Hennig suddenly begin to show his interest in this, the youngest of the Wisliceny daughters. And Hennig got far more opportunities to go to Berlin than Peter got. For the other ranks there were two weekend passes a month if they were not listed on the combat-ready sheet or assigned to guard duties. But officers were in short supply at the airship base. And, as any young officer knows, that meant that the junior commissioned ranks worked hard enough to prevent the shortage of officers, bringing extra work to those with three or more gold rings on their sleeve.

Damn Hennig! Well, Peter would show him. Little did Hennig realize it, but his insolence, and his pursuit of Peter’s girl, would be just what was needed to make Peter into the international-class pianist that Frau Wisliceny said he could become. From now on he would practise three hours a day. It would mean getting up at four in the morning, but that would not be difficult for him. There was a piano in the storage shed. Though it was old and out of tune, that would be no great difficulty. Peter could tune a piano, and there was a carpenter on the Dragon who would help him get it into proper working order, a decent old petty officer named Becker. He’d worked as an apprentice in a piano factory and knew everything about them.

For the next half-hour Peter was kept busy with his charts. Having missed his lunch, he became hungry enough to dip into his ration bag. The food supplied for these trips was not very appetizing. There were hardboiled eggs and cold potatoes, some very hard pieces of sausage and a thick slice of black rye bread. There was also a bar of chocolate, but for the time being he saved the chocolate. If they went high, where even the black bread turned to slabs of ice that had to be shattered with a hammer, the chocolate was the only substance that didn’t freeze solid. He took a hardboiled egg and nibbled at it. If he could get down to the rear-engine car, there might be a chance of some hot pea soup or coffee. The engineering officer let the mechanics warm it on the engine exhaust pipes. In some of the zeppelins there was constant hot coffee from an electric hot plate in the control gondola, but on this airship the captain wouldn’t allow such devices to be used because of the fire risk.

When his calculations were complete, Peter turned to watch the men in the control gondola. At the front was a seaman at the helm. He steered while another crewman beside him, at the same sort of wheel, adjusted the elevators to keep the airship level. This was said to be the most difficult job in the control room, although Peter had never tried his hand at it. A good elevator man was able to anticipate each lurch and wallow and turn the wheel to meet each gust of wind. The control gondola was like a little greenhouse into which machinery had been packed. The largest box, a sort of cupboard, was the radio, for keeping in touch with base and with the other airships. There was the master compass with an arc to measure the angle to the horizon, a variometer for measuring descent or climb, an electric thermometer to measure the temperature of the gas in the envelope, and there were the vitally important ballast controls. At the front, where the captain stood alongside the helmsman, was the bomb-release switchboard and a battery of lamps for signalling and for landing.

Tonight’s plan was simple: the main body of airships would attack London, approaching from over the Norfolk coast while two army airships were sent north to fool the defences by making a feint attack along the river Humber. The plan itself was good enough, although its lack of originality meant that the British would not be fooled.

And the attack started too early. Even the captain, a man whose formal naval training prevented him from criticizing the High Command or his senior colleagues, said it was a bit early when the first of the airships moved forward from the place at which they’d hovered for three hours. The whole idea of waiting was so that the sky would be totally dark when the airships crossed the English coastline. But it wasn’t dark. Even the English countryside, some six thousand feet below them, was not quite darkened. Peter had no trouble following the map. He could see the rivers, and many of the villages were brightly lit. And that meant that the British could see them. The alarms would go off, London would be made dim, and civilians would go to the bomb shelters. Worse, the pilots would stand by their planes and the gunners would load the guns; their reception would be a hot one.

All the time he watched the horizon; there was always some sort of glow from London, no matter how stringently the inhabitants doused their lights. Then he spotted it, and as they came nearer to London Peter could see the looping shape of the river Thames. There was no way that could be hidden. Suddenly the guns started. Flickers of light at first as the gunners tried to get the range, but then the flashes came closer. Staring down, Peter spotted the Houses of Parliament on the riverbank. And then the shape of London – well known to him more because of his study of target maps than because of any memories that the sight evoked – was recognizable.