По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

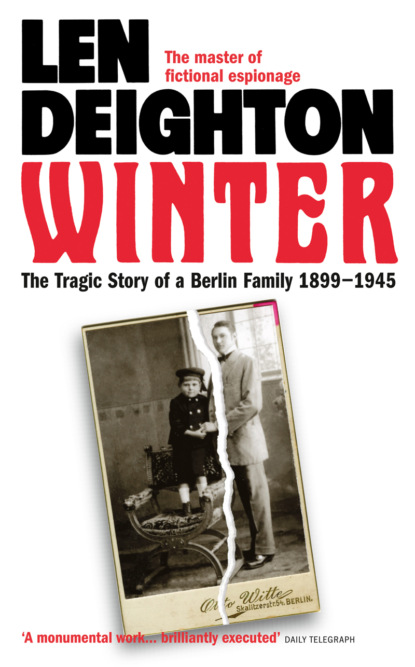

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Do you really, Harry? How wonderful you are. What is it, darling? Let me see what it is.’

‘It’s a plot of land,’ said Winter. ‘A small piece of hillside on the Obersalzberg.’

‘A plot of land? Where’s Obersalzberg?’

‘Bavaria, Germany, the very south. It’s the sort of place where a man could build himself a comfortable shooting lodge. A place a man could go when he wants to get away from the world.’

‘A plot of land on the Obersalzberg. Harry! You still surprise me, after all this time we’ve been married.’ Through the haze of the ether that was still making her mind reel, she wondered if that represented some deep-felt desire of her husband. Did he yearn to go somewhere and get away from the world? He already had that beastly girl Martha to go to. What else did he want?

‘What’s wrong?’ said Winter.

‘Nothing, darling. But it’s a strange present to give a newborn baby, isn’t it?’

‘It’s good land: a fine place with a view of the mountains. A place for a man to think his own thoughts and be his own master.’ He looked at the baby. It was happier now and managed a smile.

1906

‘The sort of thing they’re told at school’

‘You have two delightful little boys, Veronica,’ said her father. He watched through the window of the morning room as the solemn ten-year-old Peter pushed his radiantly joyful little blond brother across the lawn on a toy horse. The children were in the private gardens of a big house in London’s Belgravia. It was a glorious summer’s day, and London was at its shining best. An old gardener scythed the bright-green grass to make scallop patterns across the lawn. The scent of newly cut grass hung heavily in the still air and made little Pauli’s eyes red and weepy. Cyrus sniffed contentedly. Their English friends urged them to come to London in ‘the season’, but the Rensselaers preferred to cross the Atlantic at this time of year, when the seas were calmer. ‘No matter what I’m inclined to say about that rascally husband of yours, at least he’s given you two fine boys.’

‘Now, now, Papa,’ said Veronica mildly, ‘let’s not go through all that again.’ She was wearing a long ‘tea gown’ of blue chiffon with net over darker-blue satin. Such afternoon gowns gave her a few hours’ escape from the tight corsets that fashion forced her into for most of the day. It was a lovely, loose, flouncy creation that made her feel young and beautiful and able even to take on her parents. She pulled the trailing hem of it close and admired it.

‘She’s given Harry two fine boys,’ Mrs Rensselaer scoffed. ‘Isn’t it just like a man to put it the wrong way around? Who endured that dreadful hospital in Vienna, when there was a bedroom and our own doctor waiting for her in New York City?’ They were getting at her again, but she was used to it by now. She noticed how much stronger her mother’s high-pitched Yankee twang sounded compared with her father’s softly accented low voice. She noticed all the accents much more now that her life was spent amongst Germans. She wondered if her spoken English had now acquired some sort of German edge to it. Her parents had never mentioned it, and she knew better than to ask them.

‘I couldn’t have come home to have the baby, Mother. You know I couldn’t.’ She suppressed a sigh. For six years they’d nursed this resentment, and still it persisted.

Her father watched the children cross the road hand in hand with their nanny and heard the front door as they came in time to have a wash before tea. He said, ‘I travel across the Atlantic regularly, Veronica, and your mother usually accompanies me. It’s ridiculous for you to go on pretending that you can’t come home for a visit when we come here to London every year without fail.’ He thrust his hands into his pockets. ‘By golly, when I first came to Europe, I sailed on a four-masted barque, now your mother and I sleep in state rooms with running water, and eat dinners that wouldn’t disgrace the Ritz.’

Cyrus G. Rensselaer was a distinguished-looking man in his mid-fifties. He had a shock of black hair combed straight back, pale-blue eyes, and a large moustache. He made no concessions to the warm weather: he wore a black barathea morning suit with a fancy brocaded waistcoat, and a loose tie with a silver pin through the knot. Yet there was a certain unconventional look to him – his hair was longer than was fashionable – so that sometimes, on the steamship coming over, fellow passengers thought he might be a famous musician or a successful painter. This always pleased Cyrus Rensselaer because he often said that he would have become a painter had his father not thrashed him every time he wanted to stop studying engineering.

‘I know, Father. You’ve told me all that in your letters. But Harry is a German; the boys are German. I think of Germany as my home now.’ The difficulty was that her parents spoke no foreign languages, and their one visit to Berlin for the wedding in 1892 seemed to have deterred both of them from ever going to the continent of Europe again.

‘You were able to go to Vienna and have the baby, darling,’ explained her mother. ‘Papa feels that coming back to New York wouldn’t have been all that much more of a strain.’

‘The baby was early, Mother. We were in Vienna and the doctor said I shouldn’t travel.’ She looked at her parents; they were unconvinced. ‘Harry was furious about it. He’d made all the arrangements in Berlin. Poor little Paul – Harry used to call him “the little Austrian dumpling” until I made him stop saying it.’

Her father pulled a gold hunter from his waistcoat pocket and looked at it. ‘Didn’t your Harry say he’d be back for tea?’

‘He’s lunching at the club.’

‘He likes clubs,’ said her father.

‘It’s some mining deal…’ explained Veronica. ‘Someone has discovered a cure for malaria. They think it’s something to do with mosquitoes. Harry says that if it works it will really open up the darkest part of Central Africa.’

‘It’s not a woman, is it?’ whispered her mother.

‘No, it’s not a woman, Mother.’

‘How can you be so sure?’ her mother asked.

‘I’m sure, Mother. Harry’s not so smart about women as he is about money.’

Mr Rensselaer did not like hearing Harald Winter praised, and he certainly didn’t like to hear him praised about his investing and banking skills, at which he considered himself pre-eminent. ‘I’m surprised your Harry isn’t investing in flying machines,’ he said sardonically.

Veronica looked up at him sharply. ‘You underestimate Harry, Papa. You think he’ll invest money into any crazy scheme put up to him. But Harry is clever with money; he would never put it into the hands of people like that.’

‘I’m darned if I ever know what to make of your Harry,’ said her father. ‘He spends money on such toys as this Daimler Mercedes and then takes you down to a cabin on the Obersalzberg and makes you manage with only a couple of local servants. I didn’t pay for your education so that you could wash dishes and sweep the house.’

‘It’s not a cabin, Papa, more like a hunting lodge. The land passed to Harry because of a bad debt. He gave it to Pauli as a christening present. Now he’s built the house there. I love going there. It’s the only time I have Harry all to myself. And we take two maids from the Berlin house, as well as the cook, Harry’s valet and the chauffeur.’

‘It sounds like a lot of work for you, darling,’ said her mother. ‘And walking for five miles! We could hardly believe it when we read your letter. We couldn’t picture you walking so far. Don’t you get lonely?’

Veronica smiled. ‘I have Harry and the children; how could I ever be lonely? And, anyway, we have plenty of neighbours.’

‘What sort of neighbours? Peasants? Woodcutters?’

‘No, Papa. Some fine families have houses there. It’s become very fashionable; musicians and writers …some of them live there all year round.’

‘It sounds like an odd kind of christening present. Harry should have sold it and put the money into some investments for your Pauli.’

‘I want Pauli to have it, Papa. Last year the woodcarver in the village carved a big sign – “Haus Pauli” – that will be fixed over the gate. It’s the most beautiful place in the whole world: meadows, pine trees, and mountains. Behind us there is the Hohe Göll and the Kehlstein mountain. From the window of the breakfast room we can see for miles, right across Berchtesgaden or into Austria.’

‘It’s southernmost Bavaria. I looked on the atlas. That’s too far for us to travel,’ said Rensselaer in a voice that precluded any further discussion.

The Scots nanny brought the boys in promptly at four. Their hands and faces were polished bright pink, and a brown circle of iodine had been painted on Paul’s newly grazed arm. It was always blond Pauli who fell: he was the unlucky one. Or was he careless or clumsy, either way he was always cheery and smiling. Peter was quite different; he was dark, sober, and composed, a thoughtful little boy who’d never been babyish like his young brother. They kissed their mother and Granny and Grandpa dutifully and then, in response to the bellpull, the maids brought high tea, with the best china teacups and silver pots. And there was Cook’s homemade strawberry jam, which went onto the freshly cooked scones together with a spoonful of pale-yellow Cornish cream.

Tea was poured, plates distributed, cakes cut, and sugar spooned out. Throughout the hubbub of the afternoon tea, Rensselaer remained standing by the window; his teacup and saucer and a plate with scones and cream were on the table untouched. He had started his engineering career out west, working in places where a man soon learned how to handle hard liquor, his two fists, and sometimes a gun. The way in which he’d gained admittance to New York’s toughest business circles, and then to its snobby society families, was as much due to Rensselaer’s clumsy honesty, disarming directness, and awkward charm as to his luck and mining skills. But he’d never acquired the social grace that his wife expected of him, and this sort of fancy English tea was a ceremony he didn’t enjoy.

‘Are you keeping up the Latin?’ Rensselaer asked Peter. He was a thin, wiry child, dressed, like his little brother, in cotton knicker-bocker trousers with a sailor-suit top. He had the same dark hair that his grandfather had, and the same pale-blue eyes. There was no other noticeable resemblance, but it was enough to make them recognizably kin.

‘Yes, sir.’ Peter was a graceful little boy, slim and upright, standing face to face with his grandpa and answering in clear and excellent English.

‘Good boy. You must keep up the Latin and the mathematics. Your mother always got top grades in mathematics when she was at school in Springtown. Did she tell you that?’

‘No, sir. She didn’t tell me that.’ There was an awkward relationship between Veronica’s parents and her sons. The Rensselaers were unbending, not understanding that children were no longer treated in the formal and distant way that they had treated their daughter.

‘And what are you going to be when you grow up, young Peter?’ Rensselaer asked him. How he wished the children hadn’t had these very short Prussian haircuts. He was used to children having longer hair. These ‘bullet heads’ were unbecoming for his grandchildren, and he resented Veronica’s allowing it.

‘I’m going to fly in the airship with Count Zeppelin,’ said Peter.

His little brother looked at him with respect bordering on awe, but Mr Rensselaer laughed. ‘Airship! That’s rich!’ he said and laughed again.

Pauli laughed, too, but Peter went red. To help cover his embarrassment, Mary Rensselaer said, ‘Would you like to come and see us in America, Peter? We’d love to have you visit with us.’

‘Next year I go to my new school,’ said Peter.

‘You’re boarding them, Veronica?’ she asked her daughter.