По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

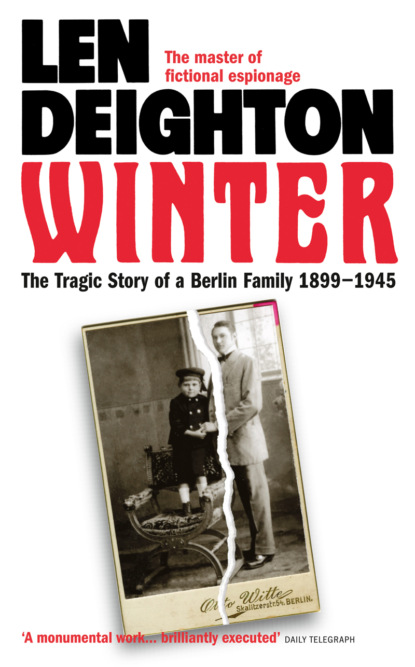

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘And what is your subject?’ said Winter, realizing that this inquiry, or something like it, was expected of him.

‘Airflow. Mach did the most important early work in Prague before I was born. He pioneered techniques of photographing bullets in flight. It was Mach who discovered that a bullet exceeding the speed of sound creates two shock waves: a headwave of compressed gas at the front and a tailwave created by a vacuum at the back. My work has merit, but it’s only a continuation of what poor old Professor Mach has abandoned.’

‘Poor old Professor Mach?’

‘He’s too sick. He’ll have to resign from the university; his right side is paralysed. It’s terrible to see him trying to carry on.’

‘And what will you do when he resigns?’ He sipped some of the bitter black coffee flavoured with fig in the Viennese style. Then he tasted the brandy: it was rough but he needed it.

Petzval stared at Winter pityingly. ‘You don’t understand any of it, do you?’

‘I’m not sure I do,’ admitted Winter. He dabbed brandy from his lips with the silk handkerchief he kept in his top pocket, and looked round. There was a noisy group playing cards in the corner, and two or three strange-looking fellows bent over their work. Perhaps they were poets or novelists, but perhaps they were Kupka’s men keeping an eye on things.

‘Don’t you realize the difference between a high-velocity artillery piece and a low-muzzle-velocity gun?’

Winter almost laughed. He’d met evangelists in his time, but this man was the very limit. He talked about the airflow over missiles as other men spoke of the second coming of our Lord. ‘I don’t think I do,’ admitted Winter good-naturedly.

‘Well, Krupp know the difference,’ said Petzval. ‘They have offered me a job at nearly three times the salary that Mach gets from his professorship.’

‘Have they?’ said Winter. He was impressed, and his voice revealed it.

Petzval smiled. ‘Now you’re beginning to see what it’s all about, are you? Krupp are determined to build the finest guns in the world. And they’ll do it.’

Winter nodded soberly and remembered how the Austrian army had been defeated not so long ago by Prussians using better guns. It was natural that the Austrians would want to know what the German armament companies were doing. ‘Count Kupka is interested in your job at Krupp? Is that it?’

‘He wants me to report everything that’s happening in their research department. By taking over the debt he can put pressure on me. That’s why I want the bank to fulfil its obligations.’ Petzval kept his voice to a whisper, but his eyes and his flailing hands demonstrated his passion.

‘It’s not so easy as that.’

‘You have the land on the Obersalzberg. It’s valuable.’

‘Even so, it might be better to do things the way Count Kupka wants them done.’

‘You, a German, tell me that?’

Warning bells rang in Winter’s head. Was Petzval an agent provocateur, sent to test Winter’s attitude towards Austria? It seemed possible. Wouldn’t such military espionage against Krupp be arranged by Colonel Redl, the chief of Austria’s army intelligence? Or was Count Kupka just trying to steal a march on his military rival? ‘It might be best for everyone,’ said Winter.

‘Not best for me,’ said Petzval. ‘I’m not suited to spying. I leave that sort of dirty work to the people who like it. Can you imagine what it would be like to spend every minute of the day and night worrying that you’d be discovered?’

‘You could make sure you’re not discovered,’ said Winter.

‘How could I?’ said Petzval, dismissing the idea immediately. ‘They’d want me to photograph the prototypes and steal blueprints and sketch breech mechanisms and so on.’ He’d obviously thought about it a lot, or was this all part of Count Kupka’s schooling?

‘It would be for your country,’ said Winter, now convinced that it was an attempt to subvert him.

‘Have you ever been in an armaments factory?’ said Petzval. ‘Or, more to the point, have you ever gone out through the gate? At some of those places they search every third worker. Now and again they search everyone. Police raid the homes of employees. I’d be working in the research laboratory and I am a Jew. What chance would I have of remaining undetected?’

Winter glanced round the café. Despite their lowered voices, this fellow’s emotional speeches would soon be attracting attention to them. ‘I’m sorry, Herr Petzval,’ Winter said, ‘but I can’t help you further.’

‘You’ll pass it to him?’ Was it fear or contempt that Winter saw in those dark, deep-set eyes?

‘You read the agreement and signed it. There was nothing to say it couldn’t be passed on to a third party.’

‘A third party? The secret police?’

‘Raise money from another source,’ said Winter. It seemed such a lot of fuss about nothing.

‘I’m deeply in debt, Herr Winter. I beg you to take the land in full payment for the debt.’

‘I couldn’t agree to that. Your prospects…’

‘What prospects do I have if Kupka prevents me from leaving the country?’

‘If Kupka prevents you from leaving Austria…’ For a moment Winter was puzzled. Then he realized what the proposal really was. ‘Do you mean that you came here hoping that I would refuse to do as Kupka demands but not tell him so until you were across the border?’

‘You’re a German.’

‘So you keep reminding me,’ said Winter. He gulped the rest of his brandy. ‘But I have business interests here, and a house. How can you expect me to defy the authorities for a stranger?’

‘For a client,’ said Petzval. ‘I’m not a stranger; I’m a client of the bank.’

‘But you ask too much,’ said Winter. He got up, reached for his hat, and tossed some coins onto the table. It was more than enough to pay for his coffee and the brandy, as well as any coffees and brandies that Petzval might have consumed while waiting for him. ‘Auf Wiedersehen, Herr Petzval.’ As Winter walked down the café he heard some sort of commotion, but he didn’t turn until he heard Petzval shouting.

Petzval was standing and shaking his fist. Then he grabbed the coins and with all his might threw them at Winter. At least two of the coins hit the glass of the revolving doors. Winter flinched. There was a demon in this fellow Petzval. Two waiters grabbed him, but still he struggled to free himself, so that a third waiter had to clamp his arms round Petzval’s neck.

‘Damn you, Winter! And damn your money! I curse you, do you hear me?’

Winter was trembling as he pushed his way through the revolving doors and out into the darkness of Gumpendorfer Strasse. Of course the fellow was quite mad, but his curses were still ringing in Winter’s head as he climbed into his horseless carriage. He couldn’t help thinking it was a bad omen: especially with his second child about to be born at almost any moment.

Winter woke up and wondered where he was for a moment before remembering that he was in his Vienna residence. It seemed so different without his wife. Usually a good night’s sleep was all that Harald Winter needed to recuperate from the stresses and anxieties of his business. But next morning, sitting in his dressing room with a hot towel wrapped across his face, he had still not forgotten his encounter with the violent young man.

Winter removed the hot towel and tossed it onto the marble washstand. ‘Will there be a war, Hauser?’ Winter asked while his valet poured hot water from the big floral-patterned jug and made a lather in the shaving cup.

The valet lathered Winter’s chin. He was an intelligent young man from a village near Rostock. He treasured his job as Winter’s valet; he was the only member of Winter’s domestic household who unfailingly travelled with his master. ‘Between these Austrians and the Serbs, sir? Yes, people say it’s sure to come.’ The razors, combs and scissors were sterilized, polished bright, and laid out precisely on a starched white cloth. Everything was always arranged in this same pattern.

‘Soon, Hauser?’

The valet stopped the razor. He was too bright to imagine that his master was consulting him about the likelihood of war. Such predictions were better left to the generals and the politicians, the sort of men whom Winter rubbed shoulders with every day. Hauser was being asked what people said in the streets. The sort of people who lived in the huge tenement blocks near the factories; workers who lived ten to a room, with all of them paying a quarter of their wages to the landlords. Men who worked twelve-and even fourteen-hour days, with only Sunday afternoons for themselves. What were these men saying? What were they saying in Berlin, in Vienna, Budapest and London? Winter always wanted to know such things and Hauser made it his job to have answers. ‘These Austrians like no one, sir. They are jealous of us Germans, hate the Czechs and despise the Hungarians. But the Serbs are the ones they want to fight. Sooner or later everyone says they’ll finish them off. And Serbia is not much; even the Austrians should be able to beat them.’ He spoke of them all with condescension, as a German has always spoken of the Balkan people and the Austrians, who seemed little different.

Winter smiled to himself. Hauser had all the pride – arrogance was perhaps the better word – of the Prussian. That’s why he liked him. Hauser steadied his master’s chin with finger and thumb as he drew the sharpened razor through the lather and left pink, shiny skin. As Hauser wiped the long razor on a cloth draped over his arm, Winter said, ‘The terrorists and the anarchists with their guns and bombs …murdering innocent people here in the streets. They are all from Serbia. Trained and encouraged by the Serbs. Wouldn’t you be angry, Hauser?’

‘But I wouldn’t join the army and march off to war, Herr Winter.’ He lifted Winter’s chin so that he could bring the razor up the throat. ‘There are lots of people I don’t like, but I can see no point in marching off to fight a war about it.’

‘You’re a sensible fellow, Hauser.’

‘Yes, Herr Winter,’ said Hauser, twisting Winter’s head as he continued his task.

‘We are fortunate to live in an age when wars are a thing of the past, Hauser. No need for you to have fears of riding off to war.’