По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

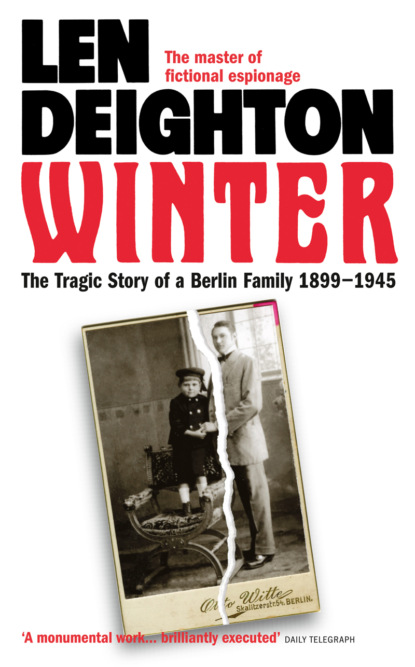

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘The wretch insisted that Veronica could not travel back to Berlin. My son will be born here. I don’t want an Austrian son. You are a German, Foxy; you understand.’

‘So it’s to be a son. You’ve already decided that, have you?’

Winter smiled. ‘Shall we crack a bottle of Burgundy?’

‘You used to like Vienna, Harald. When you first bought the house here you were telling us all how much better it was than Berlin.’

‘That was a long time ago. I was a different man then.’

‘You’d discovered your wonderful wife in Berlin and Veronica here in Vienna. That’s what you mean, isn’t it.’

‘Don’t go too far, Foxy.’

The older man ignored the caution. He was close enough to Winter to risk such comments, and go even further. ‘Surely you’ve taken into account the possibility that it was Veronica’s idea to have the baby here.’

‘Veronica?’

‘Consider the facts, Harald. Veronica met you here when she was a student at the university. This is where she first learned about love and life and all the things she’d dreamed about when she was a little girl in America. She adores Vienna. No matter that you see it as a second-rate capital for a fifth-rate empire; for Veronica it’s still the home of Strauss waltzes and parties where she meets dukes, duchesses, and princes of royal blood. No matter what you say, Harald, Kaiser Wilhelm’s Berlin cannot match Vienna in the party season. Would you really be surprised to find that she had contrived to have the second child here?’

‘I hope you haven’t…’

‘No, I haven’t spoken with her, of course I haven’t. I’m simply telling you to ease the reins on Bubi Schneider until you’re quite sure it’s all his fault.’

Winter stepped away and leaned over the gilt balcony. Resting his hand upon a cherub, he signalled to a club servant on the floor below. ‘Send a bottle of the best Burgundy up to us. And three glasses.’

They went to a long, mirrored room, the chandeliers blazing from a thousand reflections. A fire was burning at the far end of the room. The open fireplace was a daring innovation for Vienna, a city warmed by stoves, but the committee had copied the room from a gentlemen’s club in London.

Over the fireplace there was a huge painting of the monarch who combined the roles of emperor of Austria and king of Hungary and insisted upon being addressed as ‘His Apostolic Majesty, our most gracious Emperor and Lord, Franz Joseph I.’ The room was otherwise empty. Winter chose a table near the fire and sat down. Fischer stood with his hands in his pockets and stared out the window. Winter followed his gaze. Across the dark street a wooden stand had been erected for a political meeting held that morning. Now no one was there except two uniformed policemen, who stood amongst the torn slogans and broken chairs as if such impedimenta did not exist for them.

‘I’ve never understood women,’ said Winter finally.

‘You’ve always understood women only too well,’ said Fischer, still looking out the window. ‘It’s Americans you don’t understand. It’s because Veronica is an American that your marriage is sometimes difficult.’

‘You told me at the time, Foxy. I should have listened.’

‘No European man in his right senses marries an American girl. You’ve been lucky with Veronica: she doesn’t fuss too much about your other women or try to stop you drinking or going to those parties at Madame Reiner’s mansion. For an American woman she’s very understanding.’ There was a note of humour in Fischer’s voice, and now he turned his head to see how Winter was taking it. Noticing this, Winter permitted himself the ghost of a smile.

A waiter entered and took his time showing Winter the label and then pouring two glasses of wine with fastidious care.

Fischer sipped his wine, still looking down at the street. The plain speaking had divided the two men, so that now they were isolated in their thoughts. ‘The wine steward found you something good, Harald,’ said Fischer appreciatively, pursing his lips and then tasting a little more.

‘I have my own bin,’ said Winter. ‘I no longer drink from the club’s cellar.’

‘How sensible.’

Winter made no reply. He drank the wine in silence. That was the difference between them. Fischer, the rich man’s son, took everything for granted and left everything to chance. Harald Winter, self-made tycoon, trusted no one and left nothing to chance.

‘I was here this morning,’ said Fischer. He motioned down towards the street where the political demonstration had been held. ‘Karl Lueger spoke. After he’d stepped down there was fighting. The police couldn’t handle it; they brought in the cavalry to clear the street.’

‘Lueger is a rogue,’ said Winter quietly and without anger.

‘He’s the mayor.’

‘The Emperor should never have ratified the appointment.’

‘He blocked it over and over again. Finally he had to do as the voters wanted.’

‘Voters? Riffraff. Look at the slogans down there – “Save the small businessman”; “Bring the family back into church”; “Down with Jewish big business” – the Christian Socials just pander to the worst prejudice, fears, and bitter jealousy. “Handsome Karl” is all things to all men. For those who want socialism he’s a socialist; for churchgoers he’s a man of piety; for anyone who wants to hang the Jews, or hound Hungarians back across the border, his party is the one to vote for. What a rascal.’

‘You’re a man of the world; you must realize that hating foreigners is a part of the Austrian psyche. How many votes would you get for telling those people down there that the Jew is brainier than they are, or that these immigrant Czechs and Hungarians are more hard working?’

‘I don’t like it, Foxy. Lueger is becoming as popular as the Emperor. Sometimes I have the feeling that Lueger could become the Emperor. Suppose all this hatred, all this Judenhass, was organized on a national scale. Suppose someone came along who had Lueger’s cunning with the crowd, the Emperor’s sway with the army, and a touch of Bismarck’s instinct for Geopolitik. What then, Foxy? What would you say to that?’

‘I’d say you need a holiday, Harald.’ He tried to make a joke of it, but Winter did not join in his forced laugh. ‘Who is the third glass for, Harald? Am I allowed to know that?’ He knew it wasn’t a woman: no women were ever permitted on the club premises.

‘The mysterious Count Kupka sent a messenger to my home today.’

‘Kupka? Is he a personal friend?’ There was a strained note in Fischer’s normally very relaxed voice.

‘Personal friend? Not at all. I have met him, of course, at parties and even at Madame Reiner’s mansion, but I know nothing about him except that he is said to have the ear of the Emperor and to be some sort of consultant to the Foreign Ministry.’

‘You have a lot to learn about this city, Harald. Count Kupka is the head of the Emperor’s secret police. He is responsible to the Foreign Ministry, and the minister answers only to His Majesty. Kupka’s signature on a piece of paper is all that’s needed to make a man disappear forever.’

‘You make him sound interesting, Foxy. He always seemed such a desiccated and boring little man.’

Fischer looked at his friend. Harald Winter was clearly undaunted by Kupka. It was Winter’s bravery that Fischer had always found attractive. He admired Winter’s audacious, if not to say reckless, business ventures, and his brazen love affairs, and his indifference to the prospect of making enemies like Professor Schneider. Sometimes Fischer was tempted to think that Harald Winter’s courage was the only attractive aspect of this ruthless, selfish man. ‘We’ve known each other a long time, Harald. If you’re in trouble, perhaps I can help.’

‘Trouble? With Kupka? I can’t think how I could be.’

‘It’s New Year’s Eve, Harald. At midnight a whole new century begins: the twentieth century. Everyone we know will be celebrating. There is a State Ball where half the crowned heads of Europe will be seen. Why would Count Kupka have to see you tonight of all nights?’

‘It is something that perhaps you should stay and ask him yourself, Foxy. He is already twenty minutes late.’

Fischer finished his glass of wine in one gulp. ‘I won’t stay. The man gives me the shudders.’ He put the glass on the table alongside the polished one that was waiting for Count Kupka. ‘But let me remind you that tonight the streets will be empty except for some drunken revellers. For someone who was going to bundle a man into a carriage, or throw someone into the Danube, tonight would provide a fine opportunity.’

Winter smiled broadly. ‘How disappointed you will be tomorrow, Foxy, when it is revealed that Count Kupka wanted no more than a chance to ride in my horseless carriage.’

In fact, Kupka didn’t want a ride in Winter’s horseless carriage; or if he did, he made no mention of this desire. Nor was Count Kupka the desiccated and boring little man that Winter remembered. Kupka was a broad-shouldered man with large, awkward hands that did not seem to go with his pale, lined face and delicate eyebrows, that had been plucked so that they didn’t meet across the top of his thin, pointed nose. Kupka’s head was large: like a balloon upon which a child had scrawled his simple, expressionless features. And, like paint upon a balloon, his hair – shiny with Macassar oil – was brushed flat against his head.

Kupka was still wearing his overcoat when he strode into the lounge. His silk hat was tilted slightly to the back of his head. He put his cane down and removed his gloves, holding his cigar between his teeth. Winter didn’t move. Kupka tossed the gloves down. Winter continued to sip his Burgundy, watching Kupka with the amused and indulgent interest that he would give to an entertainer coming onto the stage of a variety theatre. Winter could recall only two other men who smoked large cigars while walking about in hat and overcoat, and both of those were menials in his country house. It amused him that Kupka should behave in such a way.

‘I am greatly indebted to you, Winter. It is most kind of you to consent to seeing me at such short notice.’ Kupka flicked ash from his cigar. ‘Especially tonight of all nights.’

‘I knew it would be something that couldn’t wait,’ said Winter with an edge in his voice that he did nothing to modify.

‘Yes, yes, yes,’ said Kupka in a voice that suggested that his mind had already passed on to the next thought. ‘Was that Erwin Fischer I passed on the stairs?’

‘He was taking a glass of Burgundy with me. Perhaps you’d do the same, Count Kupka?’