По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

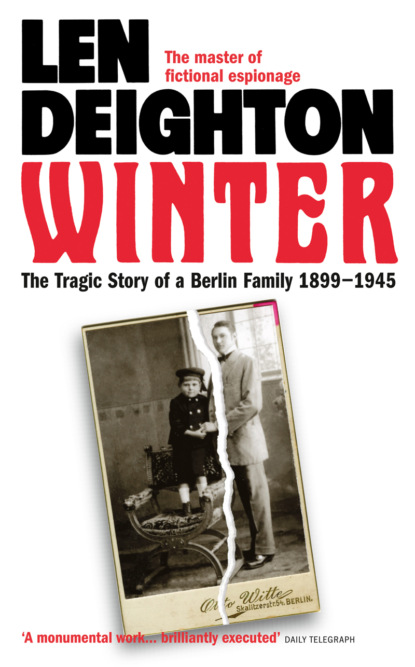

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I chose Munich because that city uniquely links Vienna with Berlin. The inhabitants of these three great German cities view each other with dispassionate superiority. While the mighty Austria-Hungary Empire dominated Europe, Vienna ruled. It was Bismarck, and the Prussian armies that in 1870 marched into Paris, that displaced Vienna and established Berlin’s ascendancy. At the turn of the century, Berlin’s music hall comics got guaranteed laughs from jokes that depicted Bavarians and the Viennese as hopeless country bumpkins. But Hitler changed all that. Hitler was an Austrian and his Nazi Party was born in Munich and when Hitler named that town as the Hauptstadt der Bewegung – ‘capital of the movement’ – all jokes about its citizens were hushed.

I visited all three cities frequently while working on this book but Munich was the place where it all began. My sons attended a local boarding school at Schondorf, and put their Austrian accents on the shelf. With the aid of my wife, I interrogated anyone old enough to provide me with memories of the old days. I was listening to the recollections of a fellow customer in a stationery shop when I spotted a small grey ‘typewriter’ that turned out to be Hewlett Packard’s radical new product. It was the world’s first laptop: a unique, strange and awkward beast by today’s standards – and started writing.

Len Deighton, 2010

Prologue

Nuremberg 1945

Winter entered the prison cell unprepared for the change that the short period of imprisonment had brought to his friend. The prisoner was fifty-two years old and looked at least sixty. His hair had been thinning for years, but suddenly he’d become a bald-headed old man. He was sitting on the iron frame bed, sallow and shrunken. His elbows were resting on his knees and one hand was propped under his unshaven chin. The prison authorities had taken from him his belt, his braces, and his necktie, and the expensive custom-made suit from Berlin’s most famous tailor was now stained and baggy. And yet the dark-underlined eyes were the same, and the pointed cleft chin made him immediately recognizable as a celebrity of the Third Reich, one of Hitler’s most reliable associates.

‘You sent for me, Herr Reichsminister?’

The prisoner looked up. ‘The Reich is kaputt, Germany is kaputt, and I’m not a minister: I’m just a number.’ Winter could think of no way to respond to the bitter old man. He’d become used to seeing him sitting behind the magnificent hand-carved desk in the tapestry-hung room in the ministry, surrounded by aides, secretaries, and assistants. ‘Yes, I sent for you, Winter. Sit down.’

He sat down. So it was all to be formal.

‘I sent for you, Herr Doktor Winter, and I’ll tell you why. They told me you were in prison in London awaiting interrogation. They said that any of us on trial here could choose any German national we wanted for our defence counsel, and that if the one we chose was being held in prison they’d release him to do it. It seemed to me that a man in prison might know what it’s like for me in here.’

Winter wondered if he should offer the ex-Reichsminister a cigarette, but when – still undecided – he produced his precious cigarettes, the military policeman in the corridor shouted through the open door, ‘No smoking, buddy!’

The ex-Reichsminister gave no sign of having heard the prison guard’s voice. He carried on with his explanation. ‘Two, you speak American …speak it fluently. Three, you’re a damned good lawyer, as I know from working with you for many years. Four, and this is the most important, you are an Obersturmbannführer in the SS…’ He saw Winter’s face change and said, ‘Is there something wrong, Winter?’

Winter leaned forward; it was a gesture of confidentiality and commitment. ‘At this very moment, just a few hundred yards from here, there are a hundred or more American lawyers drafting the prosecution’s case for declaring the SS an illegal organization. Such a verdict would mean prison, and perhaps death sentences, for everyone who was ever a member.’

‘Very well,’ said the prisoner testily. He’d always hated what he called ‘unimportant pettifogging details’. ‘But you’re not going to suddenly claim you weren’t a member of the SS, are you?’

For the first time since the message had come that the minister wanted him as junior defence counsel, Winter felt alarmed. He looked round the cell to see if there were microphones. There were bound to be. He remembered this building from the time when he’d been working with the Nuremberg Gestapo. Half the material used in the trial of the disgruntled brownshirts had come from shorthand clerks who had listened to the prisoners over hidden microphones. ‘I can’t answer that,’ said Winter softly.

‘Don’t give me that yes-sir, no-sir, I-don’t-know-sir. I don’t want some woolly-minded, fainthearted, Jew-loving liberal trying to get my case thrown out of court on some obscure technicality. I sent for you because you got me into all this. I remembered your hard work for the party. I remembered the good times we had long before we dreamed of coming to power. I remembered the way your father lent me money back when no one else would even let me into their office. Pull yourself together, Winter. Either put your guts into the effort for my defence or get out of here!’

Winter admired his old friend’s courage. Appearances could be deceptive: he wasn’t the broken-spirited shell that Winter had thought; he was still the same ruthless old bastard that he had worked for. He remembered that first political meeting in the Potsdamer Platz in the 1920s and the speech he’d given: ‘Beneath the ashes fires still rage.’ It had been a recurring theme in his speeches right up until 1945.

‘We’ll fight them,’ said Winter. ‘We’ll grab those judges by the ankles and shake them until their loose change falls to the floor.’

‘That’s right,’ he said. It was another one of his pet expressions. ‘That’s right.’ He almost smiled.

‘Time’s up, buddy!’

Winter looked at his watch. There was another two minutes to go. The Americans were like that. They talked about justice and freedom, democracy and liberty, but they never gave an inch. There was no point in arguing: they were the victors. The whole damned Nuremberg trial was just a show trial, just an opportunity for the Americans and the British and the French and the Russians to make an elaborate pretence of legal rectitude before executing the vanquished. But it was better that the ex-Reichsminister didn’t fully realize the inevitable verdict and sentence. Better to fight them all the way and go down fighting. At least that would keep his spirits alive. With this resolved, Winter felt better, too. It would be a chance to relive the old days, if only in memories.

When Winter got to the door, the old man called out to him, ‘One last thing, Winter.’ Winter turned to face him. ‘I hear stories about some aggressive American colonel on the prosecution staff, a tall, thin one with a beautifully tailored uniform and manicured fingernails …A man who speaks perfect German with a Berlin accent. He seems to hate all Germans and makes no allowances for anything; he treats everyone to a tongue-lashing every time he sends for them. Now they tell me he’s been sent from Washington just to frame the prosecution’s case against me…’ He paused and stared. He was working himself up into the sort of rage that had sent fear into every corner of his ministry and far beyond. ‘Not for Göring, Speer, Hess, or any of the others, just for me. What do you know about that shit-face Schweinehund?’

‘Yes, I know him. It’s my brother.’

One of the Americans lawyers, Bill Callaghan – a white-haired Bostonian who specialized in maritime law – said, after reading through Winter’s file, that the story of the brothers read like fiction. But that was only because Callaghan was unacquainted with any fiction except the evidence that his shipowning clients provided for him to argue in court.

Fiction had unity and style, fiction had a beginning and a proper end, fiction showed evidence of planning and research and usually attempted to impose an orderly pattern upon the chaos of reality.

But the lives of the Winter brothers were not orderly and had no discernible pattern. Their lives had been a response to parental expectations, historical circumstances, and fleeting opportunities. Ambitions remained unfulfilled and prejudices had been disproved. Diversions, digressions, and disappointments had punctuated their lives. In fact, their lives had been fashioned in the same way as had the lives of so many of those born at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Callaghan, in that swift and effortless way that trial lawyers can so often command, gave an instant verdict on the lives of the Winter brothers. ‘One of them is a success story,’ said Callaghan, ‘and the other is a goddamned horror story.’ Actually, neither was a story at all. Like most people, they had lived through a series of episodes, most of which were frustrating and unsatisfactory.

1899

‘A whole new century’

Everyone saw the imperious man standing under the lamppost in Vienna’s Ringstrasse, and yet no one looked directly at him. He was very slim, about thirty years old, pale-faced, with quick, angry eyes and a neatly trimmed black moustache. His eyes were shadowed by the brim of his shiny silk top hat, and the gaslight picked out the diamond pin in his cravat. He wore a long black chesterfield overcoat with a fur collar. It was an especially fine-looking coat, the sort of overcoat that came from the exclusive tailors of Berlin. ‘I can’t wait a moment longer,’ he said. And his German was spoken with the accent of Berlin. No one – except perhaps some of the immigrants from the Sudetenland who now made up such a large proportion of the city’s population – could have mistaken Harald Winter for a native of Vienna.

The crowd that had gathered around the amazing horseless carriage – a Benz Viktoria – now studied the chauffeur who, having inspected its engine, stood up and wiped his hands. ‘It’s the fuel,’ said the chauffeur, ‘dirt in the pipe.’

‘I’ll walk to the club,’ said the man. ‘Stay here with the car. I’ll send someone to help you.’ Without waiting for a reply, the man pushed his way past a couple of onlookers who were in his way and marched off along the boulevard, jabbing at the pavement with his cane and scowling with anger.

Vienna was cold on that final evening of the 1800s; the temperature sank steadily through the day, until by evening it went below freezing point. Harald Winter felt cold but he also felt a fool. He was mortified when one of his automobiles broke down. He enjoyed being the centre of attention when he was being driven past his friends and enemies in their carriages, or simply being pointed out as the owner of one of the first of the new, expensive mechanical vehicles. But when the thing gave trouble like this, he felt humiliated.

In Berlin it was different. In Berlin they knew about these things. In Berlin there was always someone available to attend to its fits and starts, its farts and coughs, its wheezes and relapses. He should never have brought the machine to Vienna. The Austrians knew nothing about such modern machinery. The only horseless carriage he’d seen here was electric-powered – and he hated electric vehicles. He should never have let his wife persuade him to come here for Christmas: he hated Vienna’s rainy winters, hated the political strife that so often ended in riots, hated the food, and hated these lazy, good-for-nothing Viennese with their shrill accent, to say nothing of the wretched, ragged foreigners who were everywhere jabbering away in their incomprehensible languages. None of them could be bothered to learn a word of proper German.

He was chilled by the time he turned through big gates and into an entranceway. Like so many of the buildings in this preposterous town, the club looked like a palace, a heavy Baroque building writhing with nymphs and naiads, its portals supported by a quartet of herculean pillars. The doorman signalled to the door porters so that he was admitted immediately to the brightly lit lobby. It was normally crowded at this time of evening, but tonight it was strangely quiet.

‘Good evening, Herr Baron.’

Winter grunted. That was another thing he hated about Vienna: everyone had to have a title, and if, like Winter, a man had no title, the servants would invent one for him. While one servant took his cane and his silk hat, another slipped his overcoat from his shoulders.

Without hat and overcoat, it was revealed that Harald Winter had not yet changed for dinner. He wore a dark frock coat with light-grey trousers, a high stiff collar and a slim bow-tie. His pale face was wide with a pointed chin, so that he looked rather satanic, an effect emphasized by his shiny black hair and centre parting.

‘Winter! What a coincidence! I’m just off to see your wife now.’ The speaker was Professor Doktor Franz Schneider, fifty years old, the best, or at least the richest and most successful, gynaecologist in Vienna. He was a small, white-faced man, plump in the way that babies are plump, his skin flawless and his eyes bright blue. Nervously he touched his white goatee beard before straightening his pince-nez. ‘You heard, of course…. Your wife: the first signs started an hour ago. I’m going to the hospital now. You’ll come with me? My carriage is here, waiting.’ He spoke hurriedly, his voice pitched higher than normal. He was always a little nervous with Harald Winter; there was no sign now of the much-feared professor who met his students’ questions with dry and savage wit.

Winter’s eyes went briefly to the door from which Professor Schneider had come. The bar. Professor Schneider flushed. Damn this arrogant swine Winter, he thought. He could make a man feel guilty without even saying a word. What business of Winter’s was it that he’d had a mere half-bottle of champagne with his cold pheasant supper? It was Winter’s wife whose pangs of labour had come on New Year’s Eve, and so spoiled his chance of getting to the ball at anything like a decent time.

‘I have a meeting,’ said Winter.

‘A meeting?’ said Professor Schneider. Was it some sort of joke? On New Year’s Eve, what man would be attending a meeting in a club emptied of almost everyone but servants? And how could a man concentrate his mind on business when his wife was about to give birth? He met Winter’s eyes: there was no warmth there, no curiosity, no passion. Winter was said to be one of the shrewdest businessmen in Germany, but what use were his wealth and reputation when his soul was dead? ‘Then I shall go along. I will send a message. Will you be here?’

Winter nodded almost imperceptibly. Only when Professor Schneider had departed did Winter go up the wide staircase to the mezzanine floor. Another member was there. Winter brightened. At last, a face he knew and liked.

‘Foxy! I heard you were in this dreadful town.’

Erwin Fischer’s red hair had long since gone grey – a great helmet of burnished steel – but his nickname remained. He was a short, slight, jovial man with dark eyes and sanguine complexion. His great-grandparents had been Jews from the Baltic city of Riga. His grandfather had changed the family name, and his father had converted to Roman Catholicism long before Erwin was born. Fischer was heir to a steel fortune, but at seventy-five his father was fit and well and – now forty-eight years old – Fuchs Fischer had expectations that remained no more than expectations. Erwin was a widower. He wasn’t kept short of money, but he was easily bored, and money did not always assuage his boredom. His life had lately become a long, tedious round of social duties, big parties, and introductions to ‘suitable marriage partners’ who never proved quite suitable enough.

‘You give Bubi Schneider a bad time, Harald. Is it wise? He has a lot of friends in this town.’

‘He’s a snivelling little parasite. I can’t think why my wife consulted such a man.’

‘He delivers the children of the most powerful men in the city. The wives confide in him, the children are taught to think of him as one of the family. Such a man wields influence.’

Winter smiled. ‘Am I to beware of him?’ he said icily.

‘No, of course not. But he could cause you inconvenience. Is it worth it, when a smile and a handshake are all he really wants from you?’