По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

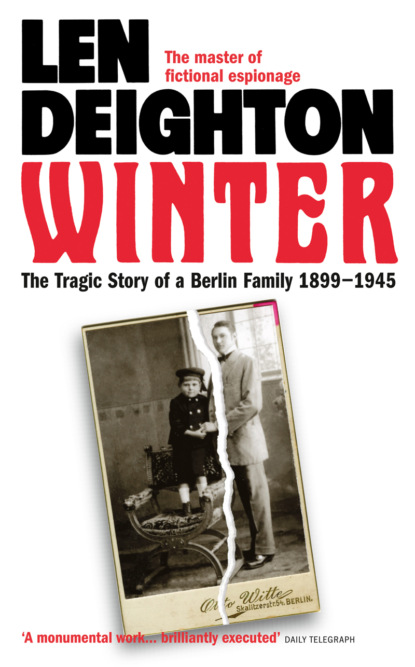

Winter: A Berlin Family, 1899–1945

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I hope not,’ said Hauser, who had no fears about riding off to war: only gentlemen like Herr Winter went off to war on chargers; Hauser’s class marched.

‘Battles, yes,’ said Winter. ‘The Kaiser will have to teach the Chinese a lesson, the English send men into the Sudan or to fight the Boers – but these are just police actions, Hauser. For us Europeans, war is a thing of the past.’

Hauser turned his master’s head a little more and started to trim the sideburns. He cut them a fraction shorter each time. Side whiskers were fast going out of fashion and, like most domestic servants, Hauser was an unrepentant snob about fashions. He always left Winter’s moustache to the end. Trimming the blunt-ended moustache was the most difficult part. He kept another razor solely for that job. ‘So the Austrians won’t fight the Serbs?’ said Hauser as if Winter’s decision would be final.

‘The Balkans are not Europe,’ said Winter, turning to face the wardrobe so that Hauser could trim the other sideburn. ‘Those fellows down in that part of the world are quite mad. They’ll never stop fighting each other. But I’m talking about real Europeans, who have finally learned how to live together, and settle differences by negotiation: Germans, Austrians, Englishmen … even the French have at last reconciled themselves to the fact that Alsace and Lorraine are German. That’s why I say you’ll never ride off to war, Hauser.’

‘No, Herr Winter, I’m sure I won’t.’

There was a light tap at the door. Hauser lifted his razor away in case his master should make a sudden move. ‘Come in,’ said Winter.

It was one of the chambermaids; little more than fourteen years old, she had a Carinthian accent so strong that Winter had her repeat her message three times before he was sure he had it right. It was the senior manager from the Vienna branch of the bank. What could have got into the man, that he should come disturbing Winter at nine-thirty in the morning at his residence? And yet he was usually a sensible and restrained old man. ‘Very urgent,’ said the little chambermaid. Her face was bright red with excitement at such unusual goings-on. She’d seen the master being shaved; that would be something to brag about to the parlourmaid. ‘Very, very urgent.’

‘That’s quite enough, girl,’ said Hauser. ‘Your master understands.’

‘Show him up,’ said Winter.

Hauser coughed. Show him up to see Winter when he was not even shaved? And this was the tricky part: shaving round the master’s moustache. Hauser didn’t want to be doing that with an audience, and there was the chance that Winter would start talking; then anything could happen. Suppose his hand slipped and he made a cut? Then what would happen to his good job?

‘I’m deeply sorry to disturb you, Herr Winter,’ said the senior manager as he was shown into the room. This time the butler was with the visitor, instead of that scatterbrained little chambermaid. Hauser noticed that the butler’s fingers were marked with silver polish. That job should have been completed last night. These damned Austrians, thought Hauser, are all slackers. He wondered if Winter would notice.

‘It’s this business with Petzval,’ said the senior manager. He had big old-fashioned muttonchop whiskers in the style of the Emperor.

Winter nodded and tried not to show any particular concern.

‘I wouldn’t have disturbed you, but the messenger from Count Kupka said you should be told immediately…. I felt I should come myself.’

‘Yes, but what is it?’ said Winter testily.

‘He died by his own hand,’ said the senior manager. ‘The messenger emphasized that there is no question of foul play. He made that point most strongly.’

‘Suicide. Well, I’m damned,’ said Winter. ‘Did he leave a note?’ He held his breath.

‘A note, Herr Direktor?’ said the old man anxiously, wondering if Winter was referring to a promissory note or some other such valuable or negotiable certificate. And then, understanding what Winter meant, he said brightly, ‘Oh, a suicide note. No, Herr Direktor, nothing of that sort.’

Winter tried not to show his relief. ‘You did right,’ he said. He felt sick, and his face was flushed. He knew only too well what could happen when things like this went wrong.

‘Thank you, Herr Direktor. Of course I went immediately to the records to make sure the bank’s funds were not in jeopardy.’

‘And what is the position?’ asked Winter, wiping the last traces of soap from his face while looking in the mirror. He was relieved to notice that he looked as cool and calm as he always contrived when with his employees.

‘It is my understanding, Herr Winter, that, while the death of the debtor irrevocably puts the surety wholly into the possession of the nominated beneficiary, the bank’s obligation ends on the death of the other party.’

‘And how much of the loan has been paid to Petzval so far?’

‘He had a twenty-crown gold piece on signature, Herr Direktor. As is the usual custom at the bank.’

‘So this small tract of land on the Obersalzberg has cost us no more than twenty crowns?’

‘The money was to be paid in ten instalments….’

‘Never mind that,’ said Winter. ‘There was no message from Count Kupka?’

‘He said I was to give you his congratulations, Herr Winter. I imagine that…’

‘The baby,’ supplied Winter, although he knew that Count Kupka did not send congratulations about the birth of babies. Count Kupka obviously knew everything that happened in Vienna. Sometimes perhaps he knew before it happened.

‘My darling!’ said Winter. ‘Forgive me for not being here earlier.’ He kissed her and glanced round the room. He hated hospitals, with their pungent smells of ether and disinfectant. Insisting that his wife go into a hospital instead of having the baby at home was another grudge he had against Professor Schneider. ‘It’s been the most difficult of days for me,’ said Winter.

‘Harry! You poor darling!’ his wife cooed mockingly. She looked lovely when she laughed. Even in hospital, with her long fair hair on her shoulders instead of arranged high upon her head the way her personal maid did it, she was the most beautiful woman he’d ever seen. Her determined jaw and high cheekbones and her tall elegance seemed so American to him that he never got used to the idea that this energetic creature was his wife.

Winter flushed. ‘I’m sorry, darling. I didn’t mean that. Obviously you’ve had a terrible time, too.’

She smiled at his discomfort. It was not easy to disconcert him. ‘I have not had a terrible time, Harry. I’ve had a son.’

Winter glanced at the baby in the cot. ‘I wanted to be here sooner, but there was a complication at the bank this morning. The senior manager came to talk to me while I was shaving. At home, while I was shaving! One of our clients died…. It was suicide.’

‘Oh, how terrible, Harry. Is it someone I know?’

‘A Jew named Petzval. To tell you the truth, I think the fellow was up to no good. The secret police have been interested in him for some time. He might have been a member of one of these terrorist groups.’

‘How do you come to have dealings with such people, darling?’ She lolled her head back and was glazy-eyed. It was, of course, the after effects of the anaesthetic. The nurse had said she was still weak.

‘It was one of the junior managers who dealt with him. Some of them have no judgement at all.’

‘Suicide. Poor tormented soul,’ said Veronica.

Winter watched her cross herself and then glance at the carved crucifix above her bed. He hoped that she was not about to become a Roman Catholic or some sort of religious fanatic. Winter had quite enough to contend with already without a wife going to Mass at the crack of dawn each day. He dismissed the idea. Veronica was not the type; if Veronica became a convert, she was more likely to be a convert to Freud and his absurd psychology. She’d already been to some of Freud’s lectures and refused to laugh at Winter’s jokes about the man’s ideas. ‘It’s a good thing you’re not running the bank, my dearest Veronica. You’d be giving the cash away to any bare-arsed beggar who arrived with a hard-luck story.’ He moved a basket of flowers from a chair – the room was filled with flowers – and noticed from the card that the employees of the Berlin bank had sent them. He sat down.

‘I want to call him Paul,’ said his wife. ‘Do you hate the name Paul?’

‘No, it’s a fine name. But I thought you’d want to name him after your father.’

‘Peter and Paul, darling. Don’t you see how lovely it will be to have two sons named Peter and Paul?’

‘Have you been saving up this idea ever since our son Peter Harald was born, more than three years ago?’

She smiled and stretched her long legs down in the bedclothes. She’d chosen two names her American parents would find equally acceptable. She wondered if Harry realized that. He probably did; Harry Winter was very sharp when it came to people and their motives.

‘All that time?’ said Winter. He laughed. ‘What a mad Yankee wife I have.’

‘You are pleased, Harry? Say you’re pleased.’

‘Of course I am.’

‘Then go and look at him, Harry. Pick him up and bring him to me.’

Winter looked over his shoulder hoping that the nun would return, but there was no sign of her. She was obviously giving them a chance for privacy. Awkwardly he picked up his newly born son. ‘Hello, Paul,’ he said. ‘I have a present for you, child of the new century.’ He was a pudgy little fellow with a screwed-up face that seemed to scowl. But the baby’s eyes were Veronica’s: smoky-grey eyes that never did reveal her innermost thoughts. Winter put the baby back into the cot.