По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

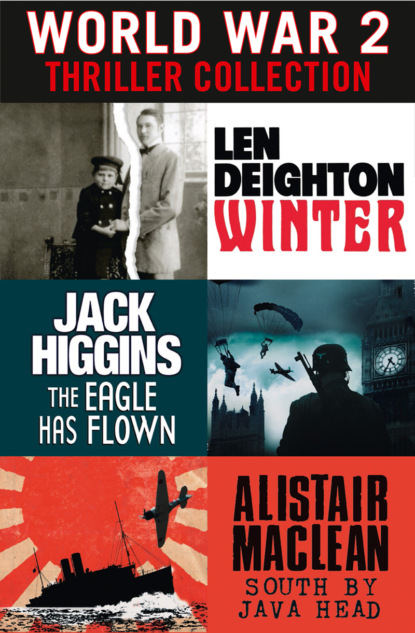

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Once, during the heavy fighting in the centre of the city, the two men met briefly with Leutnant Alex Horner. It was during the violent fighting of January 11, 1919, when Freikorps units battled their way into the Police Headquarters on Alexanderplatz, where Spartacist resistance was fierce. It was something of a massacre. The defenders’ morale was weakening as they realized that Liebknecht’s communists were not going to win power by force. Pauli and Esser were amongst the first inside the Police Headquarters courtyard. Esser lobbed a stick grenade through a downstairs window, and both men scrambled into the smoke-filled wreckage; the others followed without hesitation. Now the defenders fell back, room by room, floor by floor, but the merciless Freikorpskämpfer slaughtered everyone they found.

Alex Horner protested at the slaughter. He took his formal objections to Captain Graf. But the Freikorps men were in no mood to listen to technicalities from the regular army. They left no one alive.

The regular army, too, had men who gave no quarter. A few days later an informer reported the presence of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Leibknecht in a middle-class apartment in Wilmersdorf. The captive pair were taken to the Eden Hotel, near the Memorial Church, which the Horse Guards were using as their head quarters. After a brutal interrogation they were murdered, and with their deaths ‘Spartacus week’ ended.

During this respite the Freikorps reformed and refitted, and Lieutenant Pauli Winter lost his sergeant major. Fritz Esser had, in his brief service with his company, shown only moderate aptitude for infantry tactics, and unless Pauli was at his side he didn’t have the combat experience or the reckless bravery that most of the others showed. But there had been time to recognize the administrative skills he’d learned during his naval service. Fritz Esser was promoted to be an assistant to the battalion adjutant. Then, just two weeks later, after the adjutant was hospitalized, Esser was made battalion adjutant.

Whatever extravagant claims are made for the democratic style of the Freikorps units, there was strong opposition to making Esser an officer. So he became adjutant with that strange compromise rank that the German army invented for such social dilemmas. He was made a Feldwebel-Leutnant, so that he could do an officer’s job with officer’s badges and shoulder straps and officer’s pay without being the social equal of his peers. It was an arrangement that made all concerned very satisfied.

The man that Fritz Esser now worked alongside was Captain Georg Graf, and he was not an easy man to get along with. Despite first appearances, the little Munich-born career officer with big ears, red nose, and unconcealed homosexual preferences wasn’t a figure of fun to anyone who’d fought alongside him, anywhere from Verdun to Alexanderplatz. He was mercurial, violent and unforgiving.

Fritz Esser and Captain Graf – both men difficult and argumentative by nature – worked amicably together. Pauli Winter teased Esser that Graf had fallen in love with him, because that idea made the unmistakably heterosexual Esser nervous. Esser stoically replied that he admired Graf for his physical bravery under fire and appreciated the very real concern he showed for the men under his command. But, whatever the exact nature of the relationship, the mutual regard Esser and Graf showed for each other was genuine and lasting. And that was just as well, for Feldwebel-Leutnant Esser became Graf’s de facto second in command. When Graf was not available, Esser was always consulted. ‘What would Captain Graf probably want…?’ The question was always phrased in such a way that Esser gave an opinion rather than an order, but his underlying authority was undisputed, and Graf supported his adjutant’s decisions, whatever his true feelings may have been.

Feldwebel-Leutnant Esser’s assignment to Headquarters did not mean there was any change in the relationship between him and Pauli Winter. They were very close. Esser was grateful to Pauli for bringing him into the battalion, and though Esser could never replace his brother, Peter, in the role of mentor and protector, or Alex Horner as conscience and example, Fritz Esser was the most priceless of companions. Fritz could be outrageously funny, and he had a sharp eye for the sort of cant and humbug that the new socialist government plentifully supplied every day. Fritz was not a committed socialist; nor was he a communist or a Marxist. And whatever was the political creed that bound the Freikorps men together, Fritz Esser had no heartfelt devotion to that, either. Fritz Esser was an anarchist by both conviction and nature, and Pauli found his anarchistic attitude towards life not only amusing but illuminating and instructive, too.

When Freikorps Graf moved out of Berlin, first to Halle and then to Munich, Esser’s role as quartermaster, mother superior, slave-master and general factotum earned the respect of the entire battalion. En route there was always a hot evening meal ready, a dry place to sleep, and some sort of breakfast, too. Every soldier in the battalion had well-repaired boots and fifty rounds of ammunition in a bandolier in case there was trouble with the local populations, who sometimes preferred their communist committees to the freebooting warriors. And if sometimes they had to march too far, then that was because not even the amazing Fritz could keep all the ancient trucks in good enough repair to transport a battalion of men. Besides, soldiers marched – everyone knew that. Freikorpstruppen liked to march and shoot and sleep rough; that was why they were in the Freikorps. People who didn’t like such hardships and the comradeship that went with them remained civilians, and all good Freikorpskämpfer despised civilians of every political creed.

1922

‘Berlin is so far away and I miss you so much’

The Austrian countryside was bleak and cold, and by five o’clock in the afternoon the darkening sky was streaked with the red light of the setting sun. Martha Somló and Harald Winter had skated round and round long after all the other skaters – villagers mostly; the Viennese did not come this far to find ice – had gone.

She loved the hiss of the blades cutting into the ice, and the way her face tingled in the cold wind. She loved the harmony with which they moved together, and she enjoyed Harry’s arm firmly around her waist as they raced across the ice at reckless speed.

The dinner they were served in the private rooms upstairs at the White Horse was simple country food, but there was nothing better than a veal stew on a cold winter evening. They had their warm apple strudel, and tiny glasses of powerful Schwarzbeer schnapps from the nearby farm, while sitting in front of a roaring log fire. The logs were trimmings from the orchard, the smoke smelled of the fruit, and the sap still inside the wood made the fire crack and bang and throw sparks.

‘Must you go back tomorrow?’ she asked. They had been in bed. Now she was sitting on the floor by his feet, naked except for an ornate gypsy-style shawl that she’d wrapped herself into. He’d made her scrub off all the powder, cream, and lipstick. He cared nothing about the new fashions: in Harald Winter’s world only whores and chorus girls painted their faces.

‘I shouldn’t have stayed so long,’ said Harald Winter.

‘Why are you selling the bank?’ Every time she passed the bank in Ringstrasse she felt proud of knowing Harry.

‘Only my share of the bank.’ He stared into the fire as if hoping to see a bright future there.

‘Why?’

‘It will make no difference to us, little one. I will still come to Vienna.’ He touched her hair gently, and she closed her eyes as he stroked her head.

‘But not so often.’

‘I am not rich any more,’ said Winter. He was rich, of course, very rich by the standards that most people employ to measure wealth. But he could not provide Martha with the luxuries – the carriage and servants – that she’d once enjoyed, and he felt humiliated by his economies.

‘It doesn’t matter,’ she said. She turned to look at him by the light of the flames. He looked tired and ill, but she knew now that Harald Winter’s business setbacks affected him in the way that other men are affected by infirmities or disease. ‘I’ll always be here waiting.’

‘I’m setting up a trust fund for you in Switzerland,’ he said. ‘It will be enough to live comfortably whatever happens.’

‘You are a wonderful man, Harry. What would I do without you?’

‘Many people say things will get even worse. Some of the banks might crash. It’s better to sell.’

‘Berlin is so far away, Harry, and I miss you so much.’ He leaned forward and bent over to kiss her. If only it could be like this forever, he thought. But, just as quickly, the thought was gone. Harald Winter would find life like this unendurable after a week or so, and he was sensible enough to know that.

1924

‘Who are those dreadful men?’

The birthday party that Harald and Veronica Winter put on for their younger son, Pauli’s twenty-fourth birthday was the first real birthday party he’d had since he was a child. Although unsaid, it was his parent’s celebration of Pauli Winter’s first term at university, his return to civilian life. The lovely old house was ablaze with lights and noisy with the excited chatter of more than fifty guests and a ten-piece dance band. In a grim sort of joke that was typically berlinerisch, the invitations were overprinted upon billion-mark banknotes. Back before the war, an unskilled worker in one of Harald Winter’s factories earned twenty-five marks a week, but the staggering inflation of the previous year had seen the value of Germany’s paper money plunge to a point where one U.S. dollar bought over two and a half billion marks. Foreigners came across the border from Holland and Czechoslovakia and bought land and mansions with handfuls of hard currency. Then finally the madness ended. The Reichsbank issued its new Rentenmarks, one of which was worth one billion in the old currency. As if in celebration, Aschingers, the famous restaurant near the Friedrichstrasse railway station, offered one main dish, a glass of beer, a dessert, and as many rolls as you cared to eat for just one new mark. Inflation had stopped.

As the smoke cleared, it was apparent that the middle classes had suffered most: in the final few terrible weeks most people’s life savings totalled not enough to buy a postage stamp. But some Germans had not suffered. Harald Winter had almost doubled his fortune. Like many industrialists, he was allowed to borrow from the Reichsbank, which, in the manner of most government departments, reacted very slowly to the events of the day. Thus, even when the Reichsbank was charging its top rate of interest, Harald Winter could continue borrowing and repaying at rates far, far below that of inflation. And by 1924 the five-million-Reichsmark debt due to his father-in-law was nothing like enough to buy a meal in Aschingers. It could be renegotiated to almost anything Harald Winter decided.

But not everyone present at Pauli’s birthday party this evening had been as fortunate and as astute as Winter. Many of them had had at least a part of their money in government securities, and now they were talking about the law of December 8, 1923. The socialist government had decided that their own debts were to be advantageously revalued – for instance, the reparations due to France – but the millions of holders of now worthless government securities would not be compensated.

‘By God!’ said Frau Wisliceny, who’d come with her daughters and, to Peter Winter’s indignation, brought her son-in-law Erich Hennig. ‘I’m beginning to believe that ruffian Hitler is right about the rogues who govern us.’ Frau Wisliceny had not mellowed with age – a big, handsome, matronly woman in an elaborate but decidedly unfashionable Paris gown that she’d had since before the war. Frau Wisliceny eachewed the new fashions for the sake of which women sacrificed their long hair and exposed their legs. Her voice was firm and decisive, and she prided herself that she was as well informed as anyone in Berlin and happy to argue about art, music, or politics with any man present.

‘Surely you would not wish to be ruled by such a rascal?’ said Richard Fischer. Foxy Fischer’s son, now forty-three years old and running the family’s steel empire, had left his ageing father in order to flirt with Inge until Frau Wisliceny moved into the group. Not that Frau Wisliceny would oppose a marriage between the two of them or object to Richard’s flirting. Richard Fischer was the most eligible of bachelors, and her eldest daughter was getting to an age when to be unmarried was noticeable. But Inge had not given up hope of marrying Peter Winter, and as long as he remained single she had eyes for no one else.

‘You’d better lower your voice,’ Erich Hennig advised. ‘That little Captain Graf over there is one of Hitler’s most notorious strongarm men, and the big brute with him is his so-called adjutant.’

‘I’m not frightened to speak my mind,’ said Fischer. He, too, was a big fellow, and his full beard, the confident manner that his riches provided, made him a formidable adversary in any sort of conflict.

‘Hitler will go to prison anyway,’ said Frau Wisliceny, in an attempt to avoid any friction that might arise between her son-in-law and Fischer. ‘Even the Bavarians won’t let him get away with an armed putsch against their legally elected government.’

‘I’m not sure he will,’ said Peter Winter. He was tall and slim, with a pale complexion that had come from long hours studying his law books. In his well-fitting evening suit he was as handsome as any man in the room. He’d let his dark hair grow unfashionably long, so that it touched the top of his ears. Inge eyed him adoringly. Peter was not the sort of man every girl would want: some said he was an unbending snob, too old-fashioned for the fast-moving permissiveness of Berlin in the twenties. But Inge had decided that there could be no other man for her, and now that her sister Lisl was married…‘My class in law school went to Munich last week. We spent some time with the prosecution people, and they let us see the evidence.’

‘But there is nothing to prove,’ said Lisl. ‘Hitler’s guilty. It was an attempt to seize power by armed force. It’s simply a matter of sentencing him.’

Peter looked at her before replying. Marriage to the awful Hennig obviously agreed with her. She looked well and happy and was even more self-confident than he remembered. Most of her friends had predicted that she’d be crushed by the opinionated, dogmatic, domineering Hennig, but the opposite had happened: it was Lisl who made all the decisions, and when it came to political opinions Hennig deferred to his beautiful young wife.

Peter said, ‘You only need half an hour in Munich to realize that this is no criminal trial, it’s more like an election. What jury will send a war hero such as General Ludendorff to prison?’

Lisl replied, ‘We’re not talking about Ludendorff, who everyone knows is only half dotty. We’re talking about Hitler, a madman.’

‘I don’t know how carefully you follow Hitler’s speeches,’ Peter told her with the dispassionate moderation that he’d learned from his law professor. ‘But I read through some of his speeches. Hitler is being described as “the new Messiah” and he cultivates this. He condemns moral decay, corruption, and vice and is able to rally round him people with very differing views: that is his skill.’

‘I’ve heard all that tosh,’ said Fischer. ‘But if you listen to Hitler, you’d think that all the vice and corruption in the world are here in Berlin.’ He stroked his beard and looked to Inge for approval. She smiled at him but then turned back to look at Peter.

‘He does,’ agreed Peter mildly. ‘But that appeals to the Bavarians. Those damn southerners. They like to see Berlin as the base of centralism, the home of the Prussian military – which they fear and despise – and Protestant Berliners as the greatest obstacle to their aim of restoring a Bavarian kingdom, complete with Catholic monarchy. Hilter skilfully panders to all these feelings.’

Fischer said, ‘And those Bavarians see Berlin as a place controlled by Jewish capitalists. It suits their anti-Semitic nature.’

The band started playing a Lehár waltz. ‘It’s a crime not to be dancing,’ said Frau Wisliceny. ‘Inge, is this dance booked?’

‘No, Mama.’

Frau Wisliceny looked pointedly at Richard Fischer, who immediately asked Inge to dance.

Peter would have asked her sister Lisl to dance, if only as a way to annoy Hennig, but Hennig was too quick for him and whirled his wife away onto the dance floor with no more than a curt nod to them.