По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

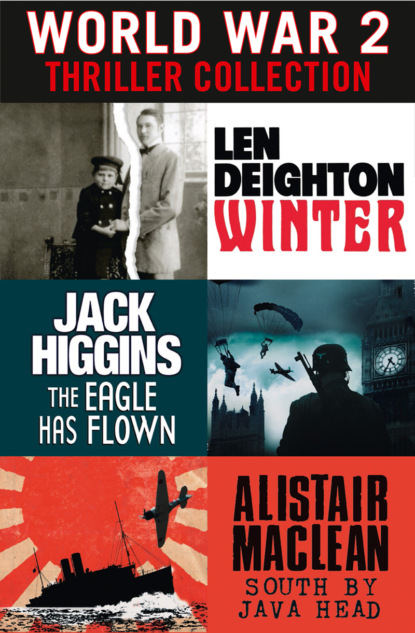

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

This evening the air here was blue with cigar smoke from the three men. The deferential attention the young man was receiving was flattering for him, but he was not surprised by it. For Leutnant Horner had recently been able to see for himself what was Germany’s most closely guarded secret: the newly established German military installations in Soviet Russia. Now the two men wanted a first-hand account of this astounding political development.

‘Did you visit all the factories?’ asked Fischer. He was seventy-two years old, totally bald and frail, but he would not give up cigars and brandy.

‘I really don’t know, but I went to some of the most important ones.’ Alex’s face had become hard and set into the inscrutable expression that the German army expected of its elite Prussian Officer Corps. His nose was wider, and the duelling scar that had been on his cheek so long had become more livid with age.

‘The Junkers airplane factories, near Moscow and Kharkov,’ supplied Harald Winter, to show he was already well informed. He looked especially sleek. He’d spent the earlier part of the evening dancing. Harry enjoyed dancing, and tonight he’d made sure of partnering most of the attractive young women here. At fifty-four he was still a better dancer than any of the younger men, and he was only too pleased to demonstrate it.

Alex Horner nodded. ‘There were twenty-three of us. We travelled separately. I didn’t, for instance, visit the poison-gas factory – it’s in a remote part of Samara Oblast – or any of the plants where artillery shells are manufactured. Ordnance specialists were sent there, and aviators reported on the flying schools. My assignment was to visit the tank training schools that we run in cooperation with the Red Army.’

Fischer crushed his cigar into the ashtray with unnecessary force. ‘I don’t like it, I’ll tell you. The idea of showing Bolshevik murderers how to use tanks and planes is madness. Those swine will attack us the first chance they get.’

‘Your fears are unfounded, Foxy,’ said Harald Winter, and smiled at the strongly expressed views. ‘The Versailles Diktat forbids us to have planes and tanks. The Soviets have not signed the Versailles treaty, and their cooperation is exactly what we need. The Russians want our expertise and we have to have secret testing grounds.’ The neatness of the deception pleased him.

‘You are being carried away by the prospects,’ Fischer told Winter. ‘I, too, want to get my factories fully working again, but I can’t keep a tank production line secret.’

Winter hesitated and a nerve in his cheek twitched. Then he admitted, ‘I have already supplied the army with modern planes. All-metal airframes. Aluminium alloys, monocoque construction, far advanced over the flimsy old wooden contraptions that were used in the war. I’d desperately like to hear how they are faring in field conditions in Russia. The army won’t let me send my technical experts there.’ He looked at Horner, half hoping that he would offer to arrange for this, but Horner looked away.

‘Perhaps I’m getting too old,’ said Fischer. ‘My son Richard thinks as you do: he’s obsessed with the designing of all these wretched tanks, to the point of neglecting our other clients. I tell him these Bolsheviks are treacherous and he laughs at me.’

‘We have a mutual enemy,’ said Horner. He blew a smoke ring and admired it. The drink and the conspiratory atmosphere had gone to his head.

‘Us and the Russians? The Poles, you mean?’ said Fischer. ‘I have never believed that Poland was a serious threat to us.’

There was a light tap at the door, and when Winter called ‘Come in’ his wife entered. Time had been kind to Veronica Winter. She had lost little of the beauty that had turned men’s heads when Winter had first met her. She was thinner now than she’d been then, and her face, throat and arms, revealed by the striped brown-and-yellow silk-voile evening dress she wore, were paler. But the serenity that made her desirable, and the smile that was so often on her lips had gone. Veronica was perturbed.

‘Harald!’ she said, having indicated that the other two men should not stand up for her. ‘Who are those dreadful men?’

‘Dreadful men?’ said Winter. ‘Which men?’ He flicked ash from his cigar. It was a sign of his irritation at being interrupted.

In an attempt to calm her Fischer chuckled and said, ‘There are so many dreadful men in your house tonight, Veronica, that even your husband can’t keep track of them.’

‘How can you say such a thing, Herr Fischer?’ she replied, feigning offence. To her husband she said, ‘Two men in some sort of uniform.’

Harald Winter said, ‘One of them is a fellow who calls himself “Captain” Graf, one of the ruffians who took his private army down to Munich to fight the communists.’

‘Pauli’s commander?’ said Veronica.

‘Yes, until our Pauli had enough sense to stay here and go to school.’

‘And the other?’ said Veronica.

‘Is there another?’ said Harald. He looked at Fischer, who shrugged, and then to Alex Horner.

Horner answered her. ‘His name is Fritz Esser. He’s a friend of Pauli’s, Mrs Winter. An old friend.’

‘The name is familiar,’ she said doubtfully.

Alex added, ‘Back before the war he lived at Travemünde. Pauli recruited him into his Freikorps and he stayed with them.’

‘The Essers,’ said Harald Winter. ‘Yes, I remember the family. They lived in the village, near Mother. It’s the little fellow who saved the children from drowning. Why do you want to know, darling?’

‘People are asking me who they are, Harald. They hardly look like friends of ours. And now this Captain Graf person has gone up to the servants’ rooms.’

Winter got to his feet. ‘Whatever for?’ he asked, but he guessed the answer before it came. There were two youngsters working in the house, and Captain Graf’s homosexual activities had been given considerable publicity. Some said that threats of police prosecution on this account were the reason he’d taken his battalion from Berlin.

Veronica blushed. ‘I’d rather not say, Harald.’

‘I’ll have the blackguard thrown out!’

Now the other two men were standing. Fischer put a hand out to touch Winter’s arm. ‘Let someone else go, Harry. Graf is a dangerous fellow.’

‘Please allow me to attend to it,’ said Alex Horner with studied casualness. ‘Graf is, I regret to say, a member of the Officer Corps. His behaviour directly concerns me.’

Harald Winter didn’t answer, nor did his wife. It was Fischer who replied to Horner’s offer. ‘Yes, Leutnant Horner. That would be the best way.’

There was a certain grim inevitability to the unfortunate business at Pauli’s birthday party. Inviting Captain Graf to such a party was undoubtedly a mistake, but no one had expected him to accept the invitation. It was only because Esser was coming that Captain Graf came, too.

Once inside the house, Captain Graf drank his first glass of champagne far too quickly. It was French champagne. Where Harald Winter had got it no one knew, but once Graf had downed one he had another and then another. Then Esser found the cognac. Captain Graf’s storm company had captured a French distillery during the 1918 offensives, and the bouquet brought happy memories of those exciting days so long ago. And Graf was a man as easily affected by memories as by alcohol. By the time he spotted the young under-footman and followed him upstairs, he was tight enough to miss his footing on the steps more than once.

Captain Graf afterwards maintained that he’d only been looking for a bedroom in which he could rest for an hour, but when Hauser – Harald Winter’s longtime valet and general factotum – stopped Graf from entering a servant’s room on the second floor, Captain Graf stabbed Hauser in the chest with a folding knife.

Hauser – in his mid-forties and gassed in the war – shouted and collapsed, bleeding profusely. One of the chambermaids heard the scuffle and found Hauser unconscious in a pool of blood. She screamed after Captain Graf, who was by then running down the back staircase with the bloody knife still in his hand.

It was Leutnant Alex Horner who intercepted Graf. He knew the house from his many visits there, and guessed Graf’s route of escape.

‘Captain Graf? I believe –’ Graf lunged at Horner with the knife, and Horner avoided the blade so narrowly that its tip slashed the front of his dinner jacket.

But Alex Horner was not the dressmaker’s dummy that Graf mistook him for. His years at the front with Pauli and the vicious trench raids that Leutnant Brand had repeatedly assigned him to had produced reactions that were as instinctive as they were effective.

Horner swung aside and, as Graf completed his unsuccessful knife thrust aimed a powerful blow at the captain’s head. It sent him reeling, but Graf was a fighter, too. He recovered his balance and lunged again, so that Alex had to retreat up the narrow servants’ corridor to avoid the slashes aimed at him. Graf grinned, but it was a drunken grin, and it encouraged Alex to take a chance. He kicked hard and high, knocking the knife aside. Horner grabbed the knife, and now it was Graf’s turn to flee.

Graf found his way down the servants’ stairs, through the pantry, and to the tradesmen’s entrance at the rear, and slammed the heavy door behind him. The wooden frame had swollen with the damp of winter, and by the time Alex had wrenched it open, run through the yard, and reached the street, there was no sign of Graf except some footprints in the newly fallen snow.

Alex Horner stopped and caught his breath. He knew enough about fighting to know when to stop. He looked up the moonlit street; there were coaches waiting to collect guests, their coachmen huddled against the cold night, faces lit by glowing cigarettes, the breath of the horses making clouds of white vapour. It was very cold, as only Berlin can be, with a few snowflakes drifting in the wind and a film of ice on everything. The city was silent, and yet it was not the empty stillness of the countryside; it was the brooding quiet of a crowded, sleeping city. From somewhere nearby came the sound of a powerful motorcar engine starting, and the squeal of tyres. That would be Graf; the fellow was often to be seen in his big motorcar.

Alex reached into his pocket for a cigarette and stood there on the street smoking as he thought about what had happened. Thank God, Graf had had plenty to drink – he’d have been a formidable adversary sober. Better to forget the whole business, he decided. Graf and his ilk had friends in high places and in the Bendlerblock the army bureaucrats were now referring to Röhm’s storm troops as the ‘Black Reichswehr’, treating them as a secret army reserve. Testifying against Graf might well mar his career prospects. Any last delusion that the army kept out of politics had long since gone. Getting promoted in this curious postwar army was like walking through a minefield.

By the time Alex Horner had finished his cigarette and returned to the party, it was almost as if nothing untoward had occurred. Hauser was in bed and being attended by a doctor, the bloodstains had been scrubbed from the carpet, the band was playing, and the guests were dancing as if nothing had happened. In fact, many of the guests were not aware of the murderous scuffie on the back stairs.

Peter Winter was dancing with a glorious girl in a decorative evening dress of a quality that was seldom seen in Germany in these austere times. The girl had brazenly approached Peter and asked him to dance. ‘I hear you’re a good dancer, Herr Winter. How would you like to prove it to me?’

Her German was not good. The grammar was adequate, but the accent was outlandish. Not the hard consonantal growl of the Hungarian or the Czech, this was a strange, flat drawling accent of a sort he couldn’t for a moment distinguish.

‘Are you Austrian?’ Peter asked.

She laughed in a way that was almost unladylike. ‘You flatterer! I heard you were a ladies’ man, Peter Winter, and now I declare it’s true. You know my German is not good enough for me to be Austrian. Is that what you say to any girl you encounter with a weird accent you don’t recognize?’

Peter blushed. It was exactly what he said to any girl whose accent he couldn’t place. ‘Of course not,’ he muttered.