По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

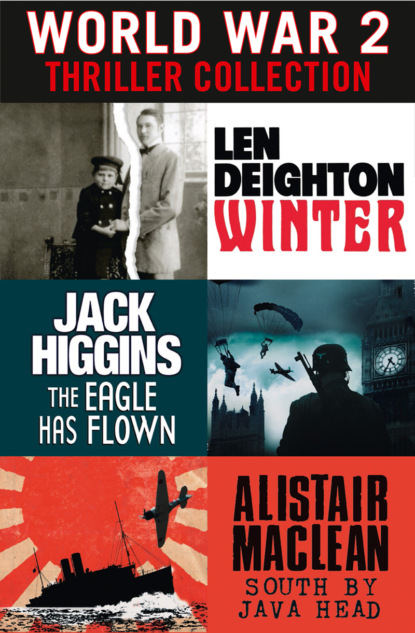

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I’m from California, U.S.A.,’ she said. ‘We’re almost family. Your mother was at school with my aunt.’

‘That’s not family,’ said Peter.

She laughed. ‘You Germans all have such a wonderful sense of humour.’ But Peter was not amused to be the butt of her joke. ‘Well,’ she said, stretching her long, pale arm towards him, ‘aren’t you going to ask me to dance?’

Peter clicked his heels and bowed formally. She laughed again. Peter felt confused, almost panic-stricken, and this was a strange, new experience for him. He wanted to flee but he couldn’t. He was afraid of this girl, afraid that she would think him a fool. He wanted her to like him and respect him, and that, of course, is how love first strikes the unwary.

‘Yes, you dance quite well,’ she said as they stepped out onto the dance floor to the smooth romantic chords of ‘Poor Butterfly’. Her name was Lottie Danziger and her father owned two hotels, three movie theatres, and some orange groves in California. She wore the most attention-getting evening dress of anyone there. It had a tubelike shape that deprived her of breasts and bottom. It was short and sleeveless, and its bodice was embroidered with bugle beads and imitation baroque pearls in the sort of Egyptian motif that had been all the rage since Howard Carter’s amazing discoveries in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. The trouble was that the beadwork was so heavy that it made Lottie want to sit down, and so fragile that she was frightened of doing so.

Lottie was like no other woman that Peter Winter had ever met. She was not like the German girls he’d known, or even like any of the Rensselaer family. She was beautiful, with pale skin and naturally wavy jet-black hair, cut very short in a style that was new to Berlin, not like the short hairstyles that were necessary to get the close-fitting cloche hats on, but bobbed almost like a man’s. She had dark, wicked eyes and a mouth that was perhaps a little too big, and very white, even teeth that flashed when she smiled. And she smiled a lot. Not the polite, tight-lipped smiles that well-bred German girls were taught, but big open-mouthed laughs that were infectious: Peter found himself laughing, too. But above all Lottie was intense; she was a fountain of energy, so that everything she did, from dancing to telling jokes about the young men she’d encountered on the ocean liner, was uniquely wonderful, and Peter was beguiled by every movement she made.

‘But I have a chaperon, darling. We couldn’t possibly go without her.’ It was her crazy transatlantic style to call Peter ‘darling’ right from the first moment, but her flippant use of the word made it no less tantalizing. Every suggestion he made for seeing her again was met with some wretched rule about her chaperon. She was playing with him: they both knew that she could meet with him alone if she really wanted to, and it was this that put an extra edge on their exchanges. She was so desirable that his need for her pushed all other thoughts and aspirations out of his head.

‘But you don’t look like a Rensselaer,’ she said, having for a moment silenced his attempts to arrange another meeting. She swung her head back to see him better and cocked it on one side, so that her dark, wavy hair shone in the lights. ‘No, you don’t look like a Rensselaer at all.’

She was teasing him, of course, but he readily joined her game. ‘And what do the Rensselaers look like?’

‘Gorgeous. You have only to look at your mother to know that. The Rensselaers are the most beautiful family in the whole of New York. Why, when your uncle Glenn came back from the war he must have been getting on for forty years old, and yet there wasn’t a girl in the city who didn’t dream of capturing him. The groans and gnashing of teeth when he married were to be heard from Hoboken to Hollywood. Your uncle Glenn came here just after the war, didn’t he?’

‘He was an Air Corps major attached to the Armistice Commission. He wanted Mother to go back to New York, but Father was against it.’

‘Why?’

‘He said it would look bad. All through the war he’d been saying that Mother was at heart a German. That was how he prevented her from being interned. How would it look, he said, if when the Allies won she went running back to America?’

‘Her parents are too old to travel, and they’d give anything to see her again.’

‘Papa was adamant.’

‘Do all German families obey Father so readily?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Peter.

‘In America your father would find life more difficult. You should have heard what my father said when I first told them I was coming to Europe.’

‘What did he say?’

‘He cut me off without a penny, darling,’ she said with a laugh. ‘But eventually he came around.’ She hummed the melody: ‘“Poor Butterfly”, it’s such a beautiful tune, isn’t it? I never hear it but I think of the war: all those poor butterflies that never came back.’

‘Yes,’ he said without being sure that he understood. Until now he’d not liked Americans, not the Rensselaers, not President Wilson, not any of them. They were not easy to understand. But this one – with her hair bobbed almost like a man’s, and the fringe that came down to her eyebrows – was captivating. As he swung her past a huge arrangement of fresh-cut flowers, she extended her hand so that the fingertips brushed the blooms. It was a schoolgirl’s gesture – she had to show the world how happy she was. Perhaps all Americans were like that: they were not good at secrecy, they had to demonstrate their emotions.

They danced on until they passed Inge Wisliceny dancing with Richard Fischer. Inge looked especially beautiful tonight. Long dresses and deep necklines were becoming on her. Lottie let go of Peter’s hand to wave to her. Inge smiled sadly as they whirled past and disappeared. ‘And where is your uncle Glenn now?’ she asked.

‘Heaven knows. Somewhere in Europe. Every few weeks we get a postcard from him. He visits now and again and he’s always sending gifts of food. He thinks we’re starving.’

‘Many Germans are starving,’ Lottie reminded him. ‘But Glenn was always generous. He was my favourite man. I was eighteen when he got married. I cried to think I’d lost him. I went to the East Coast just to be a bridesmaid. Handsome, clever and brave.’

‘And rich, too,’ said Peter sardonically. He was getting rather fed up with this eulogy to Glenn Rensselaer.

‘Not your uncle Glenn. He cares nothing for money, but his father is rich, of course.’

‘My grandfather, you mean; yes, he got rich from the war,’ said Peter. ‘They say that one out of every ten trucks the American army used came from a Rensselaer factory.’

‘You’re not going to be one of those boring people who want to blame the war on war profiteers.’

‘So many people died,’ said Peter. ‘It’s obscene to think that the fighting made anyone rich.’

‘So what would you prefer?’ she said. ‘That the government own everything, make everything, and decide how much money each and every citizen deserves?’

‘It might be better.’

‘You’d better stay away from politics, Peter Winter. No one will believe that you could be so dumm as to want to deliver yourself to the politicians.’

‘Yes. Long, long ago my brother, Pauli, told me more or less the same thing.’

There was something touching about Peter Winter when he admitted to his shortcomings. ‘You’re adorable,’ she said and brushed her lips across his cheek. He caught a whiff of her perfume. ‘Why are you staring at me?’ he asked.

‘I know you so well from your photographs. Your grandmother has pictures of you everywhere in their house in New York. And in the room where I practised piano there is a photo of you at the keyboard. You must have been about ten or twelve. They told me you practised three hours every day. Is it true?’

‘I’ve given up the piano. I haven’t touched a piano for years.’

‘But why?’

‘My hand was injured.’

‘Where? Show me.’ She pulled his hand round into view. ‘That? Why that’s nothing. How can that make any difference to a real musician?’

‘I can’t play Bach with a fingertip missing.’ For the first time she heard real anger in his voice, and she was sorry for him.

‘Don’t be so arrogant. Perhaps it will prevent your becoming a professional pianist, but how can you not play? You must love music. Or don’t you?’

‘I love music.’

‘Of course you do. Now, tomorrow you will visit me and I will play some records for you. Do you like jazz music?’

‘It’s all right.’

‘If you think it’s only all right, then you haven’t heard any. Tomorrow you’ll hear some of the best jazz music on records. I brought them from New York with me. You’ll come? I’m staying with the Wislicenys.’

‘I know. Yes, I’d be honoured.’ Listening to jazz music was a small price to pay for being alone in her room with this wonderful girl.

‘The really great jazz is not on records. You should hear it in Harlem. Although you have to go to the black people’s brothels in Memphis or New Orleans to hear the real thing.’

Peter Winter turned his head away so that she didn’t see his embarrassment. Even in this degenerate, wide-open city of Berlin one didn’t expect well-brought-up young ladies to know what a brothel was, let alone to mention it in conversation with a man.

‘Are you looking for someone?’ she asked.

‘My brother.’ It was not true, but it would do.