По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

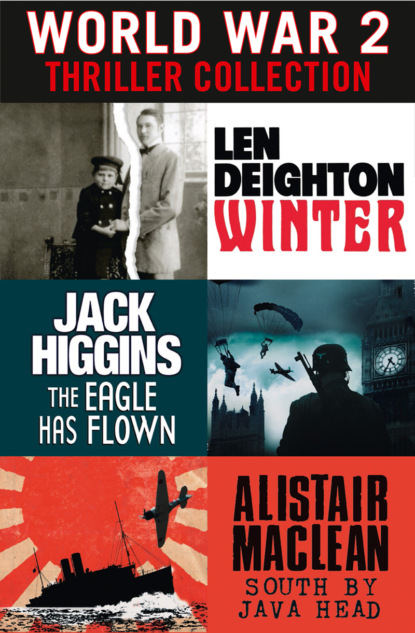

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Few sailors of the Naval Division had seen any action in the war. Typically they were unmarried ex-factory workers with no fixed addresses. Some of them went on regular forays of looting and housebreaking and even demanding money from well-dressed people in the streets, always disguising their crimes with neat political labels. The sailors remained in the Imperial Palace because they were being provided with payments by the government – who were frightened of them – and because it was warmer and more comfortable than the street to which they would otherwise be relegated. As long as Liebknecht and Luxemburg encouraged them, they would cheer the Spartacists’ speeches.

The men of the Freikorps were a totally different proposition, as Esser pointed out. The Freikorps recruits came largely from front-line soldiers. For these men the world was divided into ‘the front’ and ‘the rear’. The rear were the civilians who’d made so much money in the war factories and the bosses who owned them. The rear were the bankers and the financiers, the pacifists who’d made speeches against the war, and the ‘November criminals’ who’d signed the armistice. Although officers were excluded from the People’s Naval Division, the Freikorps soldiers readily included their battle-hardened officers as part of their exclusive fraternity.

Perhaps it was while compiling his neglected report that Fritz Esser began to discover something about himself. Esser had never been in battle. His naval service had been spent in the comparative comfort and the indisputable safety of Imperial Naval barracks. And although he’d never admitted it, Esser felt uneasy about his passive role in this great ‘war to end wars’, for Esser – despite his revolutionary declarations – had the inborn respect for the warrior that so burdens the German soul.

Endless bickering, inarticulate committees meeting long into the night without reaching any conclusions, had wearied and disillusioned him. And on this Monday evening, the 23rd day of December, 1918, Esser had reached the end of his patience. The prospect of the Imperial Palace coming under attack by loyal units of the army frightened him, and he made no secret of his fear. Even the light artillery that informers said were being readied at Potsdam would be enough to blow the main doors in, and the effect of shrapnel fire in these confined spaces would not bear thinking about.

And yet trying to get this simple fact understood by his committee had proved far beyond his power. Not that any of the committee members offered a sensible alternative to his suggestion that they open talks with Ebert and release their hostages – Otto Wels in particular – as a gesture of good faith. He was shouted down by cries of ‘Traitor!’ and ‘No surrender!’ rather than defeated in rational discussion. Finally Esser exploded with rage. He yelled obscenities at these pompous pen-pushers – Bonsen, he called them – and stormed out of the meeting. It was then that the messenger came to say that two army plenipotentiaries were waiting for him downstairs. This was the beginning of the end. He felt frightened. Now what was he supposed to do? Temporize, yes, but how?

‘I am Esser, committee chairman. What is it?’ Esser fixed them with his dark, piercing eyes. Pauli immediately recognized his friend, who’d grown into a barrel-chested giant, pea jacket open, red neckerchief at his throat and sailor cap on the back of his close-cropped head.

‘Fritz! Remember me, Pauli Winter? Travemünde.’

Esser didn’t recognize Pauli. His eyes went to Alex Horner. He recognized Horner from the meeting in the Chancellery; he was some sort of military side to Otto Wels. It was to be expected that the army would send him to parley about the release of Berlin’s military governor. Esser had opposed the idea of holding the socialist politician here as hostage: it was nothing better than kidnapping and extortion. Such tactics would not endear the People’s Naval Division to the working class. Esser knew the working class: they were moralists.

‘Come away from the palace, Fritz. I want to talk to you.’

Esser went to the window. It was dark outside, but he could see the crowds. He thought he could see the lights from the cathedral shining on steel helmets. But steel helmets didn’t mean that the army had arrived; half the population of Berlin seemed to be wearing steel helmets and carrying guns. He turned back to look at the two men. The fellow from Wels’s office was unmistakably a Prussian officer, despite the bowler hat, walking stick and long overcoat. The other was dressed in a battered army greatcoat and a steel helmet with a swastika painted on the front. They shouldn’t have let him in here with that pistol strapped to his belt, but it was too late now.

‘Fritz!’ said Pauli once more.

He recognized him now. The kid from the big house at Travemünde: Paul Winter. Perhaps it was going to be all right. He grabbed the young man’s outstretched hand. ‘What the devil are you doing here? Did the army send you?’

‘The army? No.’

‘Good God, Pauli, the guards only brought you in here because they thought you were sent by the army to negotiate with us.’

‘Come and have a beer, Fritz.’

Esser turned to Alex Horner. ‘You haven’t come here to ask for the release of Otto Wels?’

Alex was on the point of saying, to the devil with Wels. Instead he told Esser, ‘Herr Winter is my friend.’

‘Then let’s go and drink beer!’ said Fritz Esser loudly. He smiled to show his crooked teeth. ‘I’ll buy you more beer than you can drink, young Winter.’

‘That might be a lot of beer, Fritz.’

‘It’s not a trick?’ said Esser, his face suddenly darkening.

‘You have my word,’ said Alex Horner formally. He clicked his heels.

‘My friend is a Prussian stuffed-shirt,’ Pauli told Esser, ‘but under that shirt there is a goodhearted fellow.’

‘I’ll trust you,’ said Esser. It seemed a long time since he’d trusted anyone very much, but now he wanted to shed the worries of the day and forget, forget, forget. Let those know-it-alls of the committee continue their arguments without him. ‘Where shall we drink?’ Just to be on the safe side, he strapped a belt and pistol around his waist. He ran his hand over his bristly hair and felt his scalp damp with sweat, then plonked his cap back on his head.

Pauli had his answer ready: ‘There’s a Kneipe behind the Spittelmarkt: Guggenheimer’s place. Know it?’

The choice of venue reassured Fritz Esser. Guggenheimer was a Jew with half a dozen children, all of whom attended the university, with varying degrees of success. His bar was a student hangout with cheap food and strong beer. All sorts of odd people went there. It was the sort of place that a sailor, a Freikorps man and a smartly dressed civilian might be able to drink together without getting unwelcome attention.

Alex stole a glance at his friend. Had it all been planned by Pauli? He could be devious and cunning: it was a part of his nature that few people knew. And yet Pauli was sincere, too; that was what so beguiled Esser.

‘The pay is not important,’ said Pauli Winter after several tankards of Guggenheimer’s best dark beer had been consumed. ‘It’s the comradeship: men you can trust with your life. Good fellows, every one of them. But the money is good, too. Every volunteer has a daily basic pay of forty marks, and now the government are adding another five. Then there’s the food: two hundred grams of meat and seventy-five grams of butter and a quarter-litre of wine. Plenty of beer and cigarettes, too.’ He held up his beer. ‘In our canteen this would cost us almost nothing. But a lot of the men join because Freikorps service counts towards their pension. Take you, Fritz,’ he added, as if taking an example entirely at random. ‘You’d be taken into the Freikorps at your present naval rank and pay – in fact, you’d become my sergeant major, because I’m getting my own company next month – and your Freikorps service counts towards your pension. Plus the regular family allowance will immediately start again for your parents. How are they, by the way?’

‘My father is not well,’ said Fritz Esser absent-mindedly.

‘I’m sorry to hear that,’ said Pauli. It was a part of Pauli’s charm that he could express his genuine sorrow that the ‘pig man’ was unwell, then immediately continue his description of life in the Freikorps, without seeming uncaring. ‘People who can handle the administration side are difficult to find. The storm battalions were not noted for their paperwork. But now we can only get pay, allowances, food and all the other supplies we need if the office work is properly done. These socialists are all bureaucrats, you see; we have to play their game.’

‘Why do we have to play their game?’ Esser inquired. ‘I don’t trust this government.’

Alex nodded agreement and leaned forward to hear Pauli’s reply.

‘For the time being,’ said Pauli. ‘When the right time comes, Germany will have proper leadership.’

‘An emperor?’ asked Alex Horner.

‘Perhaps,’ said Pauli. ‘But somehow I think we’ve seen the end of the House of Hohenzollern. His Highness lacked the qualities of a true Prussian soldier-king, and no one who’s seen the Crown Prince at close quarters would hope he’d be any better.’

‘Heartily agreed,’ said Alex Horner, and belched. Esser took off his old patched jacket and hung it over the back of his chair. His bare arms were covered with tattoos: serpents, girls’ names and expressions of fidelity in elaborate scrollwork.

‘Get more beer,’ said Pauli.

‘It’s my turn,’ said Fritz Esser. He was the oldest of the three men and determined to pay his way. He got up and walked to the counter with only the slightest unsteadiness.

With Esser out of earshot, Alex Horner whispered, ‘You’ll never recruit this wretch to your damned Freikorps Graf.’ Alex didn’t like Captain Graf, the diminutive homosexual who ran his private army like some medieval war-lord, but he was cautious about voicing such thoughts to Pauli who’d become something of an apologist for this strange man.

‘There’s not one there who could take on the job of a sergeant major,’ said Pauli.

‘Not one where?’

‘In the company that I’ll take over next month. Good soldiers, good fighters, good comrades, but no skewer upon which I can fix them.’

‘You’ll never do it, Pauli. The fellow’s a Spartacist.’

‘He’ll see reason,’ said Pauli complacently. ‘Fritz is a sensible fellow.’

‘You mad fool. Did you have this in mind right from the start?’

Before Pauli answered, Esser was back with three foaming steins of beer. He slammed them on the table. ‘Drink, drink, drink,’ he urged. He looked round to see who was seated nearby. ‘And then there are a couple of things you must tell me about this Freikorps business.’

Fortified with several litres of Guggenheimer’s beer, the trio went down Leipziger Strasse, visiting various bars, until they turned north along Friedrichstrasse, where the nightlife was even more raucous: male and female prostitutes mingling with beggars, drunks, and pickpockets, and from every side the frantic sounds of recently arrived American jazz.

Fritz Esser never went back to the Imperial Palace. When, early on that Christmas Eve morning, the army’s artillery opened fire on the palace, Esser didn’t even hear the gunfire, for he was in an upstairs room over a club behind the Schiffbauerdamm Theatre, asleep in the arms of a half-undressed nightclub hostess.

As 1918 tottered to a close, Fritz Esser was enrolled in the Freikorps. On the other side of the city, Liebknecht joined his Spartakusbund to the Independent Socialists and the Revolutionary Shop Stewards, called his new political entity the Communist Party of Germany, and began arming his supporters.

Everywhere in Berlin the madness continued: lines of hungry people formed outside the bakers’ shops, and butchers’, too, and stared into expensive restaurants, where war profiteers and their gloriously attired women gobbled champagne and caviar. On the Western Front the Allies had stopped fighting but their naval blockade continued, and thousands of Germans died of malnutrition. Throughout Europe the influenza virus decimated the tired and hungry population; it brought death to seventeen hundred Berliners in a single day.

Whatever reservations Fritz Esser had had about serving under the command of his young friend they soon evaporated as Pauli Winter led his company across the rooftops of Wilhelmstrasse despite Spartacist snipers across the street. Soon Pauli had repaid any debt he owed Esser for hauling him from the sea so long ago. More than once Pauli saved his sergeant major from death or injury. Once his strong arms saved Esser from sliding off the rain-swept slates into the street below. Esser had followed Graf and the others along the ridge of a saddleback roof. It required balance, daring and speed, and Fritz Esser, burdened with rifle, bandoliers, and a heavy bag of grenades, had none of these in adequate amounts. He slipped on the icy ridge tiles, and his rifle went across the slates and down into the street far below. As Esser started to fall, Pauli grabbed him by the greatcoat collar and held him spread-eagled across the steep roof, while men on the roof on the far side of Wilhelmstrasse fired at him. Only with great difficulty was the unfortunately heavyweight Esser dragged to safety. Pauli laughed about it. Under fire the clumsy Pauli became another man: not just commander of ‘Winter Company’, he was also the most audacious and skilled fighting man in that very formidable unit, Freikorps Graf.