По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

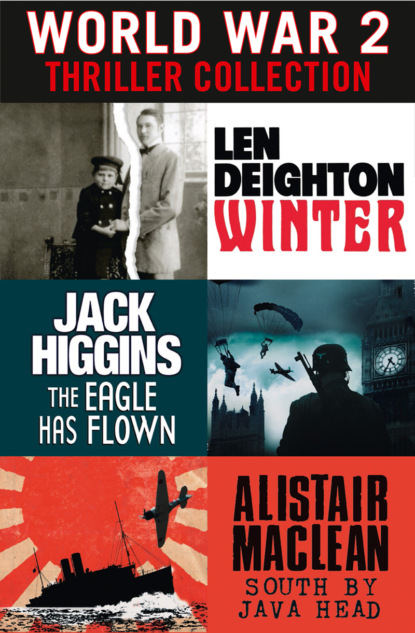

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Behind Pauli the bugler was sounding ‘close up!’ the prearranged call to indicate the way through the defences.

‘Koch! Get back, damn you.’

Once through the last of the wire, Pauli pushed ahead of his sergeant major. In the storm companies it was a matter of pride that the company commander led his men into battle. More bullets came now: closer, for they no longer zinged but cracked like a ringmaster’s whip. Chest-high. Alongside him, two men bowed low to die, heads down, snorting and gurgling briefly as the blood flooded into their lungs. He ran on, stumbled and touched the silk stockings – or, rather, made a gesture in the direction of his throat – Monike had said that she would be his good luck. It was a childish thing to say, for she was a child, and he believed it, because, for all his brutal experiences, he too was little more than a child. She hadn’t given him the stockings, of course. She was not that sort of girl. He’d taken them from the laundry basket in her bedroom.

More firing of rifles and machine guns. Over to the left – and very close – there came the sound of a heavy Vickers gun, stertorous, like a wheezing generator. But it was too late now to worry about bullets. Pauli found himself on the brink – the parapet – of the foremost enemy trenchline. He jumped. It was almost three metres deep. Burdened as he was with bombs and machine pistol, his weight took him right through the damp duckboards that formed the floor of the trench. The rotten wood snapped with a loud noise, and Pauli went deep into mud, so that he had to bend and extricate his boots from the broken slats. Thank God this section of the trench was unmanned.

He ran along the trench, splashing his way through the stagnant, watery mud. God! Did the British stand in this shit night and day. He came to a surprised looking British soldier. Pauli pulled the trigger of his pistol and the youngster was punched backwards by the force of the bullets. He sank down without any change in the expression upon his pinched, pale face.

Pauli ran on, along the communications trench and then to a junction of the support trench. Here the conditions were even worse: he was ankle-deep in stinking mud. The trenches were unmanned here. Had the British gone over the top to face the attackers, or fled? A sign marked the rear trench ‘Pall Mall’, and there were other painted wooden signs pointing the way to Company HQ and a field dressing post.

The trench lines zigzagged to minimize the effects of blast. At the next turn half a dozen khaki-clad soldiers were bunched in the corner of the entrance to a dugout. They were wide-eyed with fear. Two of them were sitting on the fire step hugging themselves. Their uniforms were blackened with rain, and the heavy wet cloth hung on them like a dead weight. Pauli swung aside. From behind him Koch fired a burst from his MP 18, and the brown-coated soldiers stiffened and grew taller before toppling full-length like lead toys.

As they ran forward again, a British officer put his head out of his dugout immediately ahead of them and shouted loudly. He was a middle-aged fellow with a neat moustache. He looked not unlike Pauli’s father.

Pauli stopped, undecided what to do, but Koch hit the officer with the butt of his gun and then threw two stick grenades down through the dark entrance and raced on. There was a tremendous bang and muffled screaming. Pauli looked back. He saw the British officer as the blast caught him. The wretched man was blown to pieces in a pink cloud of blood. The mangled body, its khaki sleeve and insignia intact, hit the sides of the trench. Round the upper part of the arm was a mud-stained white armband with a red cross on it. The dugout was of course a temporary casualty station. Too late now.

Ahead of them the sound of firing and, emerging from the white fog, more men. ‘Wer da?’ He climbed up one of the trench ladders and ran along the edge of the parapet.

‘Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot!’ They were Germans from the next company. ‘Wer da?’ More challenges as grey-uniformed men appeared like wraiths in the dispersing fog. Pauli recognized the faces of some of them. The bugler sounded the close-up signal again. Pauli saw their officer, a captain named Graf, a thin, irritable man with a red nose, his heavy steel helmet grotesquely large for his small ferret face.

‘Keep going, Winter. We’ve got them on the run.’

‘Ja, Herr Hauptmann.’ He turned and shouted to the rest of his men to hurry. The Punishment Battalion had changed Pauli. At one time he would have been terrified by a man like Hauptmann Graf. Now it took a great deal more to frighten him.

There was a loud roar behind him, and the narrow trench was suddenly lit by a brilliant orange glow. Pauli turned to see the great balloons of ignited fuel ripping a hole through the white fog. The flame throwers were systematically burning out the dugouts all along the support trench. Poor devils – even a bayonet in the guts is better than that.

They hurried on; the earth was firmer behind the support trenches and the fog much thinned. Crossing the sunken road that the British had used for their supplies and reinforcements, the Germans chased across the open ground. No one was firing at them now. To the left was a forest of tree stumps, the trunks short, broken, and bared white like pencil stubs. To the front of them the ruins of a village, with only waist-high walls remaining. The church had been devoured by the war: its relics and valuables stolen, its doors and pews chopped into firewood, the roof collapsed, its lead improvised into drains for waterlogged trench-lines, and its tower reduced to rubble by artillery fire to deprive the British of an observation post.

Behind the village were twenty or thirty brown-clad soldiers, British service troops without rifles, an officer wearing the badges of the Royal Engineers, and two men carrying wooden crates. At the first sign of the Germans they raised their hands in the air. The Germans, in too much of a hurry even to rob them, pointed back the way they’d come. Reluctantly the British shambled off to the east, walking slowly, in the hope that a counterattack would free them before they got to the German rear.

In the ruined village was a mobile bath unit. It had been abandoned hastily by men who’d left behind parts of their uniforms, towels, webbing and even a rack of Lee-Enfield rifles. But even the sight of clean hot water and the wonderful fragrance of disinfectant and soap did not halt the advancing Germans.

They pressed on. Pauli was fit and strong, but the pace was wearing. He sniffed the air. Was it gas? And if so what type? Not mustard gas anyway. That was the one most to be feared, but the plan of attack said that the artillery would only put mustard into British rear areas, into which the Germans would not advance. So it couldn’t be mustard. Could it? He stopped and bent down to prod loose a clod of earth and sniff at it. Foolhardy, but it was what was expected of men in the storm companies. He started running again and swung his gas mask round to the front of his belt as he ran. Soon they slowed: the pace was too demanding even for young, fit bodies, and there was no sign of the enemy.

Walking now. The girl came back to his mind. The house was empty, she said, her parents visiting her grandmother. They’d kissed and ended up in bed. First time for Pauli and first time for the girl. What a fiasco. All his sexual fantasies shattered by two minutes in bed. The girl had cried. I’m still a virgin, she’d said. Then, her mood changing, she’d laughed. Well, it wasn’t funny for him. He’d fled from the house with only the stockings around which to weave stories for his fellow soldiers. But by the time he’d got back to his company, he had no wish to mention her to anyone. There was no one to whom he could confide his story. He was in love; he wanted her too much to talk about her. What a fool he’d been. If only he’d let the relationship develop at its own pace. Then perhaps he wouldn’t have got the letter telling him that she never wanted to see him again. He blamed himself unceasingly: a girl you meet in church doesn’t expect to be treated like a whore.

Twice they were halted by pockets of determined resistance: fierce Scots veterans whose rapid, accurate rifle fire caused severe casualties among the by-now careless Germans. Soon the regiment’s trench-mortar units arrived, and after a relentless pounding the Scotsmen came out, calling, ‘Kamerad!’

By this time it was late afternoon and already the wintry daylight was beginning to go. They moved on again. They were all more cautious now, and tired. On the left, the bugler for the next company was sounding rally. Pauli stopped and his bugler did the same. Time for reforming, and a moment for the fleet of foot to recover their breath and the slower men to catch up.

A runner from Battalion Headquarters told him to consolidate his position and take possession of a British twelve-inch howitzer battery several hundred metres to the west. They found it without trouble. Hauptmann Graf was already there. His men were energetically plundering the enemy stores.

The captured battery was a revelation to the German storm troops. The Germans were trying on the superb sheepskin coats that the British supplied to their sentries, and there were many who wanted one of the fine leather jerkins. More than one fellow was striding around in British officers’ hand-sewn leather boots. In the officers’ mess were all manner of forgotten luxuries, including Stilton cheese, smoked salmon, and a dozen unopened cases of Scotch whisky.

Pauli looked around with interest and apprehension. These were specially selected and well-trained soldiers. Given the order, they’d abandon their booty and continue the advance. But what of the ordinary German conscripts behind them? What would they be doing tonight?

Pauli decided that such conundrums were best left to the generals. He went to report to Captain Graf. ‘It’s disgraceful,’ said Graf. He took off his heavy helmet. He was a jug-eared little man, gnomelike: a homosexual it was whispered. But homosexual or not, Graf was a fearless soldier, respected by every man in the regiment. ‘Shells were ready and fused. I blame the officers. No attempt to disable the guns: dial sights in position, breech blocks in full working order. It’s disgraceful.’

‘Yes,’ said Pauli, amused that Graf should be so indignant about the enemy’s lack of soldierly dedication.

‘Cowards.’

‘We must have come five kilometres,’ said Pauli. ‘There’s never been a breakthrough like this before.’

Captain Graf grunted. He was smoking and holding in his hand a gold-coloured tin of fifty English cigarettes. ‘Try one,’ he said and offered the open tin.

Pauli lit one up and, after breathing out the smoke, said, ‘If the advance has been the same all along the battlefront, we must have captured a huge piece of ground.’

‘Like them?’ said Graf. ‘English cigarettes: damned good.’

‘Yes,’ said Pauli. He’d never smoked anything so delicious. He studied the pale tobacco appreciatively and decided that if he ever became rich enough he’d smoke such cigarettes all the time. In the sandbagged shelter behind Graf, one of the men had found a gramophone and was winding it up. ‘Do you think we’ll go all the way to the coast, Herr Hauptmann?’

‘The coast?’

‘The war is won, isn’t it?’

‘Look at those stores, Winter,’ said Captain Graf, turning to look at the German soldiers gobbling the captured food. ‘Last week I severely punished four of my men who’d ground up horse fodder to make flour. They said they were hungry. They were, of course. We are all hungry. We ration out the shells to our artillery. We don’t have enough rubber to make more gas masks.’ He blew smoke. ‘Have you seen what’s in that mess hut, Winter? Food for the rank and file. Tinned beef, plum jam, good white bread, that yellow English cheese. Did you see how much of it there is? They told us the English were starving, didn’t they?’ He sniffed. ‘No, the war is lost, Winter. The courage of our young men and our meagre supplies of shells and bullets can’t prevail against this sort of plenty.’

‘The war is lost?’ said Pauli. Captain Graf was a tough regular officer from a good regiment, not the sort of fellow who was easily discouraged.

‘The war is lost,’ said Graf. ‘No matter how much ground we occupy, we cannot win.’ The gramophone started playing ‘Poor Butterfly’. For a moment the two officers listened to it. ‘Get your casualty returns sorted out. The infantry will be close behind us. They’ll pull the storm companies back later tonight, or before first light in the morning.’

Pauli looked to where Koch and other men of his company were sitting on the ground, too exhausted even to join in the plundering. How could the war be lost? It wasn’t fair; it just wasn’t fair.

‘The damned war’s not over’

‘I wish to God that you’d stop saying the war’s over,’ Peter told his father. He was propped up on an armchair in the drawing room of his parents’ house in Berlin. His dark-blue naval officer’s tunic was resewn where it had been ripped, and the gold was missing from one sleeve of it. His left leg was in splints and his face badly bruised. ‘The damned war’s not over and perhaps never will be.’

‘They signed the armistice nearly two months ago,’ said his father gently. His son was in pain and frustrated by his immobility.

‘The British navy is still blockading us. Our people are starving. The warships of the High Seas Fleet have red flags flying from their mastheads. There are bands of armed ruffians in the streets shooting at each other. That traitor Liebknecht has been carried shoulder-high through the streets by soldiers wearing the Iron Cross – and has made a speech from the balcony of the Royal Palace. The army has disintegrated. The Kaiser has run away to Holland. How can we negotiate a peace treaty? We have nothing to bargain with.’ It was a cry of pain. The defeat seemed to have affected Peter more deeply than any of the rest of the Winter family. Attacked in the street by a group of Spartacists, he’d been knocked to his knees by clubs and rifle butts. There is little doubt that this drunken, vicious little mob would have killed him, but for another mob that came along and started a brawl, during which Peter escaped. Since then he’d been confined to the house and had done nothing but stare out the window and brood on the consequences of the chaos in the streets below.

Pauli Winter got up from the armchair. He was wearing the better of his two army uniforms. It was far from the elegant costumes in which Prussia had sent officers to war. Its motley stains had not been removed by scrubbing and cleaning, and its shape not been improved by regular baking in the delousing ovens. The fine leather boots he’d gone to war wearing were long since lost and he wore simple boots and grey puttees like the ones worn by the storm troops. ‘I must get back to Battalion Headquarters,’ said Pauli. ‘I’ll see you tomorrow, Peter.’ He was in fact on a twenty-four-hour pass, but Pauli found that a couple of hours in the gloomy house near Ku-damm was all he could endure. He’d bought a few cheap presents from a department store in Leipziger Strasse, and now he placed them carefully under the Christmas tree in the corner. One of the servants had found a few logs, and today, with Christmas so near, a fire was burning in the stove. On the sideboard he noticed that all the family photos were arrayed, their silver frames gleaming. There they were in 1913, the happiest of happy families: two smiling children and Mama and Papa standing proudly behind them. How long ago it seemed. The family had changed dramatically since then. Now – with riots in the streets and Bolsheviks occupying Winter’s factories – even a log on the fire was a treat to be relished. Harald Winter was stunned by the sudden change in his fortunes, and Peter had become a crusty invalid. Now it was Mama who held them all together, ventured onto the streets, coaxed food from the shopkeepers, and persuaded the servants to keep working.

‘Battalion Headquarters! With that ridiculous little Captain Graf in command,’ said Peter scornfully. ‘You still go on pretending, do you? Your Freikorps battalions are just a lot of uniformed gangsters, and Graf is no more than a brigand.’

‘That’s not true,’ said Pauli. It was because they were so close that Peter knew where to put the knife. ‘The Freikorps is a fine organization and the army fully approves. There are thousands of us: disciplined and armed. And not just in Berlin – they are being formed all over Germany. Every one of our soldiers is a volunteer signed on month by month. In the East they will be defending our borders now that the army are withdrawing. The Poles, and the rest of them, would have been looting Berlin by now if it wasn’t for the Freikorps units out there.’

‘Then why don’t you march eastwards?’ said Peter.

‘Because, like you, we are temporarily immobilized. When the transport and our orders arrive, perhaps we’ll go.’ Pauli’s tone was mild, not just because he remembered the good times they’d shared, but because he was frightened that Peter might thoughtlessly blurt out something about the court-martial and Pauli’s assignment to a punishment battalion. He’d do almost anything to prevent his parents from finding out about that.

‘An under-strength battalion commanded by a captain?’ said Peter sarcastically. ‘Four machine guns, an antique tank, and two armoured cars? What sort of battalion is that?’

‘The next time the Reds try to take over Berlin, you’ll see,’ said Pauli. He put on his field-grey overcoat and steel helmet and tightened the strap under his chin before reaching for his belt and pistol.

‘What’s that crooked cross sign you’ve painted on your helmet?’ his father asked.