По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

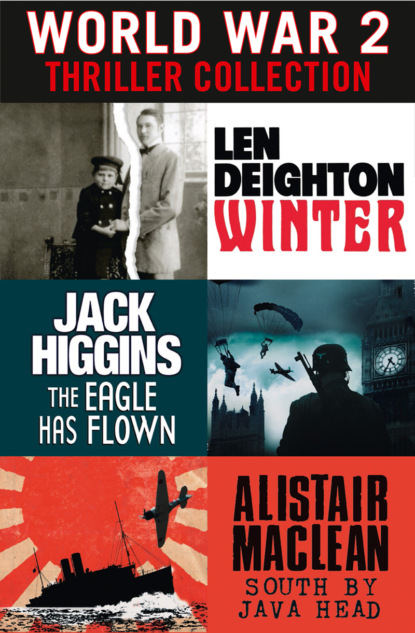

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘It’s not so easy when you are up there,’ said Peter. ‘In this sort of poor light, through the overcast, it all looks grey. In evening or morning sunlight the shadows make it easier.’

‘Then why do they always come over in such bad weather?’ said Pauli.

Peter gave a grim smile. It seemed so safe and simple to those who stayed on the ground. ‘The poor devils want to disappear into the clouds if our fighters get near them or the anti-aircraft fire does.’ As he said it, small black puffs of flak appeared in the sky to the south, but they could see no sign of the artillery-spotting plane.

‘The fliers won’t hang around long,’ said Pauli. ‘And these long-range guns can fire only a few rounds at a time. Then the barrels are worn out. War is a damned expensive business, as the taxpayers are discovering.’

‘When we win, the French will pay reparations, as they did last time.’

‘Ah! When we win,’ said Pauli.

They stood in silence, looking at the shattered landscape. The grounds of the château had been beautifully cultivated for a couple of hundred years, but now the whole place had been ravaged by the soldiers. The orchard was no more than tree stumps, the lawn a camp, and everywhere a quagmire. Farther away, the woodland had been scavenged for firewood through three winters of war; and the country roads, built for carts and carriages, were churned by endless divisional horse-drawn traffic and the occasional staff car and truck.

‘Was it terrible?’ asked Pauli, still staring out the window. ‘The zeppelin flights, the raids over England, and the crash: was it terrible?’

‘The raids were all right. I didn’t realize what danger we were in until, on the final one, I saw an airship burn in the sky.’ Peter’s voice was different now: the voice Pauli remembered from when they’d exchanged confidences in the darkness of the nursery. ‘I was so frightened, Pauli, that my hands were shaking. She was gone…. The whole airship was gone in a few seconds. So many friends…’

‘And you crashed.’

‘That wasn’t so bad but they operated on my hand three times and I was convinced that I would relive my fears … scream or reveal my cowardice under the anaesthetic.’

‘And did you?’

‘God knows.’

‘Papa told me that most of your crew were killed.’

‘We were hit over the English coast – gunfire – the control gondola was damaged and we lost some of the officers. We limped back across the North Sea, sinking lower all the time. I thought we’d get home in one piece, but it was not to be. Most of the casualties came when we hit the trees. The observation officer, an elderly chap named Hildmann – the staff captain just now put me in mind of him – was killed. While he was alive I didn’t ever give Hildmann a thought, but after he was dead I realized how much I owed to him. He’d looked after me right through all the training flights and on our first war missions over England. After a man is dead you can’t say thank you.’

‘And Hennig was with you?’

‘He survived, the insolent little swine.’

‘And he’s married Lisl Wisliceny, I hear.’

‘Yes, a flashy ceremony – Frau Wisliceny arranged it all, of course – and a big reception in the Adlon afterwards.’

‘Mama wrote me a letter.’

‘Mama had to go: Frau Wisliceny is her best friend. She’s a fine woman. Yes, Mama went, but Papa was in Friedrichshafen with the airship people.’ Peter said it with satisfaction. He was pleased that his father had found a reason to stay away from the wedding of the hateful Hennig.

‘Did you want to marry her?’

‘Lisl? Yes, once I did. Or at least I thought I did. But then, as I realized the way in which she was playing a game with me and Hennig – playing us off one against the other – I didn’t love her any more.’

‘They’re all pretty girls, the Wislicenys.’

‘I was close to Inge once…’ He turned suddenly. ‘By God! I’ve just thought of something. If America has declared war, Mama is an enemy alien. They might make us resign our commissions, Pauli.’

‘You’re a selfish pig, Peter. Instead of worrying about your commission you should be worrying about poor Mama. She must be feeling terrible about it. Let’s pray she’ll not be sent to an internment camp like the English civilians have been.’

‘Yes, of course, you’re right. I should have been thinking of her. But it will affect us, too, Pauli. It could make things very difficult for both of us.’

A light tap came and the office door opened immediately. A man stepped inside, a formidable figure, a captain, fortyish, with hard grey eyes and a mouth like a rat trap. He nodded to Peter and without any preliminaries asked Pauli for his papers. Pauli knew it was the end for him as soon as he saw the metal gorget at his neck. A Feldgendarmerie officer complete with Bavarian-style shako, and sword hung with ornamental knot. ‘You are absent without leave, Leutnant Winter. You have absented yourself from your post while on active service. From the front line …It’s a death-penalty offence. I suppose you know that?’ A slight Bavarian accent: it wasn’t the voice or the manner of a career soldier, but there was that touch of informality that professional policemen use to make apprehended men amenable. Pauli guessed that he’d once been a senior police officer in Munich or some such town.

Pauli didn’t reply. He knew what was expected of a Prussian officer. He stood rigidly at attention, as he’d stood for so many hours on the parade ground at Lichterfelde. He’d known, deep down, that it was going to happen, and now it had happened. His guts were churning, but in some ways it was a relief. Now all he had to do was face his punishment. He’d always been better able to face the consequences than to worry about them.

He had plenty of time to think about what he’d done. He was held for two nights in the cells at Divisional HQ before facing his court-martial. But for his colonel, Pauli would probably have faced a firing squad. It was the colonel – prematurely aged from sending so many youngsters into battle – who gave such a glowing account of Pauli’s bravery and devotion to duty. It was the colonel who put such emphasis on Pauli’s extreme youth, and it was the colonel who arranged that Leutnant Brand did not appear in person.

But Brand’s written deposition was carefully worded. He must have spent many hours upon the document, and he covered every eventuality, even to the extent of finding the military policeman with whom Pauli had spoken at the crossroads.

The verdict was inescapable.

The sentence came like a slap in the face, but Pauli didn’t flinch. Six months with a Punishment Battalion. Everyone knew that a spell with a Punishment Battalion was intended as a deferred death sentence. Such units were used only where the fighting was most bitter and the personnel were considered expendable. But the one consolation was that his Field Post Office address didn’t reveal what had happened, so his parents believed he was simply transferred to another regular infantry regiment.

And thus it was that Pauli endured the worst of the fighting of that year, so that afterwards some men did not believe that he could be a veteran of so many infamous fields of battle. But he did not survive the year unharmed. Though his skin was intact, his soul was hardened – ‘as hard as Krupp steel,’ he sometimes claimed after a few drinks. He had learned to suffer without complaint, to hurt without whimpering, and to kill without emotion.

And yet, paradoxically, there were aspects of him that stayed unchanged. Outwardly he remained genial, careless, clumsy Pauli. He was too anxious to please ever to become really sophisticated. And now more than ever he relished the simple pleasures of life. Unlike his brother, Peter – who was austere, cultivated and brimful of ambition – Pauli served his sentence and went back to active duty asking no more than to sit down now and again to a big bowl of beef stew, smoke twenty cigarettes a day and have an extra half-hour in bed on Sunday morning.

1918

‘The war is won, isn’t it?’

Leutnant Pauli Winter had never been in no-man’s-land like this before. He’d never known it in the full foggy raw light of morning. Like all the other front-line infantry, he’d come here only at night, on patrols to mend the great jungle of rusty barbed wire, which was constantly damaged by shell and mortar fire, or to raid the enemy trenches. Always under cover of darkness.

Until now his world had consisted only of narrow trenches and dark dugouts. The sky, seasonally grey, azure, or black with rain clouds, had been only a narrow slot framed by the muddy edges of the trench parapet. No one in his right mind raised his head above the parapet to stare across at where the unseen English inhabited their own subterranean dominion.

It was impossible to remember all the stories he’d heard about no-man’s-land. There were stories about fierce animals that were said to live out here, skulking in their warrens and emerging by night to feast on the dead and dying. And certainly some of the noises they’d all heard encouraged the belief. Other soldiers’ stories said there were men living out here in this great churned-up rubbish tip. Deserters of all nationalities were said to have formed a community, a bandit gang, who lived deep in the ground, stole money, watches and personal possessions from the bodies that littered the ground, and fed upon stores plundered from both sides of the line. It was all nonsense, of course, but hugging the ground out here, the barrage whistling overhead, the earth stinking of cordite, faeces and decomposing flesh, made such yarns seem only too likely.

But today was March 21, 1918, the start of the great attack that was going to break the British-held front line and end the war with a victory for the Kaiser. Pauli and two of his company – his runner and his youthful sergeant major – were crouched in a shell crater about a hundred metres in front of the German lines. The rest of his company were similarly hidden nearby, and so were other ‘Storm companies’ crouching unseen in no-man’s-land all along the front line.

The three men had their hands clamped over the sides of their heads to protect their eardrums against the deafening roar of the German guns. The preparatory bombardment had been going on for nearly five hours. Now it was nine-forty and the guns would stop, and in the pearly light Pauli would lead his men into the attack.

‘Nothing could have lived through that,’ shouted Feldwebel Lothar Koch as the artillery fire lessened. Koch was young – he’d given a false age to get into the army – a pimply fellow with a square protruding jaw that moved as he chewed on a plug of tobacco. Partly due to the immense pride his promotion had given him, he was still optimistic about the outcome of the war. Deep down in his heart, young Koch entertained the hope of being commissioned, or at least becoming a noncommissioned deputy officer by the time he took part in the promised victory parade through conquered Paris. He looked at the other two men with his mournful eyes. They both stared back at him blankly. ‘Nothing could have lived through that,’ repeated Koch.

Pauli touched the silk stockings under his collar: black, a pair of them knotted to form a long scarf that wound around his neck five times. It prevented the collar of his uniform from chafing his neck, and also reminded him of a glorious few hours in Brussels with a girl he’d met in church! He looked at his pocket watch – wristwatches did not survive in these conditions – and up at the heavy fog. Thank God for it. He dragged himself to his feet. His uniform was caked with mud; his canvas bag of stick grenades felt heavier than ever. ‘Bugler!’ he shouted and from a muddy hillock nearby the bugler slowly pushed up through a chrysalis of heavy mud. ‘Sound the advance.’

On every side German ‘storm troops’ emerged from the incredible collection of broken debris that littered the ground. They met with the clattering sound of a British Lewis gun and some intermittent rifle fire from Tommies who had not been rendered useless by the artillery’s systematic destruction of the British front line trenches. But the fog was too thick for the British to see what was happening, and the fire that greeted their advance was aimed into the white mist, so that only a few unlucky Germans screamed and fell. Pauli heard calls for stretcherbearers and a bugle sounding the advance.

‘Is the company advancing?’ Pauli asked the young Feldwebel. There was mud in his mouth and he spat it out and wiped his face with a dirty lace handkerchief. Her handkerchief! Her name was Monike. She spoke the Belgian sort of Plattdeutsch that he could understand. A tall, slim, shy creature with wonderful green-grey eyes, heart-shaped face, and all the mysterious promises of a first love. She’d taken him home and given him chicken soup that her mother had left on the stove for her. Thick chicken soup with beans and carrots. He loved Monike. He thought of her every day. And wrote her long letters, every one of which he carefully tore up.

‘Yes, Herr Leutnant. The company is advancing.’ Koch could see through the fog no better than his company commander, but they both knew that the men would do as they were ordered. They were Germans, and their readiness to obey instructions was a measure of their civilization, and their tragedy.

Pauli kept running over the uneven ground. With the swirling white fog wrapped round him, he stumbled into pot holes and tripped over the roots of trees, sandbags, corpses, balks of ancient timbers, and large sheets of corrugated iron that, together with untold other stuff, littered this old battlefield. The intelligence reports said no-man’s-land was two hundred metres wide at this place, but now it seemed much wider.

Sergeant Major Koch, a thin, wiry figure, was just a few paces ahead of him: hurrying as best he could, ungainly and uncertain about the going. His machine gun was slung over his shoulder, and in his hands he held a huge set of heavy-duty wire cutters. Bullets zinged past but the German bombardment was now no more than a few desultory bangs and crashes far in the enemy’s rear areas. How soon before the British artillery and mortars began to lob their explosives into no-man’s-land? Surely they must have guessed that the five-hour bombardment was a prelude to an infantry assault. Or were the British pulling their howitzers and field artillery back into safer, rear areas. Such defeatism was too much to hope for. Or was it.

Now Koch had started cutting through the wire. The artillery had done their job well; endless fields of wire – so carefully tended by the night patrols from both sides – were now a shambles. Koch found the weakest parts of this metallic thicket and cut a path just wide enough for the infantry to follow through. The wire sprang back with a loud noise like a peal of bells. At night such carelessness would have brought a burst of fire and almost certain death, but now speed was all that mattered. The stolid Koch, crouched low, went chopping his way through the undergrowth of rusty tendrils.