По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

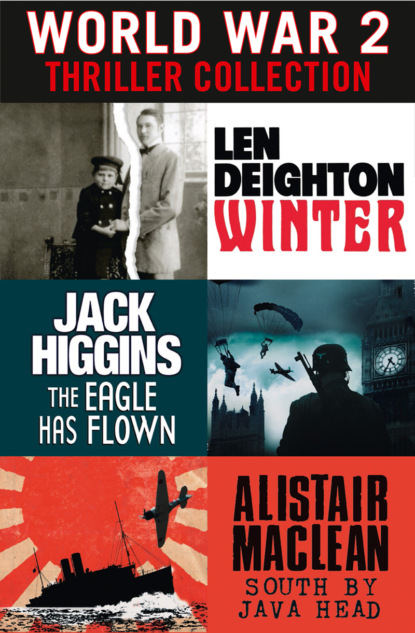

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘That would be impossible,’ said the secretary. He was an elderly man with rimless spectacles, bushy eyebrows and a celluloid collar that was going yellow at the edges, like the documents that were to be seen on every side.

‘Try,’ suggested Alex, and the sailors vociferously agreed.

Now there were more arguments and some telephone calls. Everyone who might have placated the sailors had gone to lunch, and the revolutionaries were becoming angrier every minute.

Before the problem was resolved, a messenger came rushing into the lobby with an urgent request for Alex Horner. He must go immediately to the office of Herr Otto Wels. Wels had been kidnapped.

It was not difficult to discover what had happened. Wels’s staff were standing in the corridor talking in loud voices. Some of the women were sobbing. They told how another group of sailors had entered the building by a side door, found their way upstairs, and demanded the Christmas-bonus money from Wels. Wels was heard to say they’d get no money until he had the key.

Which of the sailors was the first to strike Wels makes no difference, for soon he was beaten and frog-marched back to the Imperial Palace, which the sailors obviously had no intention of leaving. According to a message that Alex received later that day from a paid informer, Wels was beaten with rifle butts and thrown into a rat-infested cellar.

That afternoon a large party of the sailors went back to the Chancellery. They were in a bitter frame of mind. They pushed their way into the lobby, posted armed guards at every exit, and took control of the Chancellery telephone exchange. No one – not even the Chancellor – would be permitted to enter or leave the building. They had Wels as a hostage and they wanted their money.

Pauli had listened to Alex Horner’s long story with intermittent attention. He’d studied the other people in the bar, with particular interest in the younger women. He’d had so little free time since the war began – so little time amongst civilians that he’d still not got accustomed to the shorter skirts and the display of female ankles. Women had worn full-length skirts since ancient Greece; surely there was something apocalyptic about the new fashion. If not apocalyptic, certainly provocative, especially when some of the younger ones wore these flesh-coloured stockings!

Between them they’d finished one bottle of wine and were nearly at the bottom of a second one. Now Pauli realized that Alex had reached a stage in his story when some contribution from Pauli was expected. ‘What did you mean about the sailors’ finding out something tomorrow?’

Alex glanced back over his shoulder to be sure he wasn’t overheard. Next door the gypsy band was playing sad Hungarian ballads. ‘The Chancellor used the secret telephone link to summon help from the army. Groener is sending troops. We’ll crush those Red swine once and for all.’

‘Sending them here? To the Royal Palace?’

‘The government is a prisoner, Pauli. They are being held hostage by those people. Groener has ordered several squadrons of the Imperial Horse Guards from the Potsdam barracks to march. They’ll be here by midnight.’

‘Will the troops fire on the sailors?’

‘The Imperial Horse Guards have remained loyal to their officers. There are a few other reliable men coming. Artillery, too. They’ll blast their way into the palace.’

‘The sailors won’t stand much chance against artillery.’

‘They’ve brought it on themselves. I’ve no sympathy for those gangsters.’

‘That fellow Esser you mentioned. I know him.’

‘The petty officer?’ Alex’s blasé mask dropped and he registered surprise. ‘How the devil did you come to know a fellow like that? From the Punishment Battalion?’

Pauli laughed. ‘No, the real rogues don’t end up in the Punishment Battalions, Alex. The real ones end up as generals. We both know that.’

Such remarks made Alex nervous. He looked round again to make sure they weren’t overheard; even so he disassociated himself from such sentiments. ‘I’m not sure about that, Pauli,’ he mumbled.

‘I’d like to try and get Esser out of there,’ said Pauli.

‘Get him out?’

‘He’s a good sort.’

‘There are no “good sorts” there, Pauli. They are all scum.’

‘I can’t leave him to be killed,’ said Pauli. ‘He was my friend. He’s the son of a villager from where my grandparents lived.’

‘It’s too dangerous,’ said Alex.

‘Don’t be a fool,’ said Pauli. ‘No one’s going to harm me simply for going along to the palace to have a word with Esser.’

‘You’re in uniform.’

‘A private’s uniform.’

‘These people are mutineers, Pauli. One look at you and they’ll know you’re a member of the Officer Corps. And the Freikorps is the avowed enemy of the revolution.’

‘I’ll have to go. Was it midnight you said the soldiers will arrive?’

‘On your honour, you mustn’t warn them,’ said Alex.

Pauli smiled. ‘You must be joking, Alex. No secrets remain secret in this town for more than half an hour.’

‘Then I shall come with you. Perhaps I can persuade them to release Wels.’

‘That would be a feather in your cap, Alex.’

Alex nodded seriously and swigged the last of his Riesling. ‘The more I come to think of it, the more amusing it sounds. Let’s go, Pauli.’

It was only a short walk down Unter den Linden from the Adlon Hotel to the Imperial Palace. As they came out of the hotel, the street was illuminated by the lights of the British Embassy. The Armistice Commission were said to be using it, but there was no sign of British soldiers there. From the far side of the Pariser Platz, close to the Brandenburg Gate, they heard a brass band playing energetically: a Christmas carol. It sounded like a military band, but there was no way to be sure. Beyond the gate, the Tiergarten was being used as a military camp, but no one knew the allegiance of the soldiers. Probably the men were just remaining close to the army soup kitchens that had been set up there. Half a metre of snow had fallen upon Berlin, and the sounds of the city were muffled under the white blanket, so that even the music of the band was distant and muted. They plodded on, icy impacted snow under their feet.

‘You’ve changed, Pauli. You’ve changed a lot.’

‘We’ve grown older,’ said Pauli, dismissing the idea. His father was always talking about the way Pauli had changed. Hadn’t Peter changed? Hadn’t Mama changed? And hadn’t Harald Winter changed most of all?

‘It’s more complicated than that,’ persisted Alex. ‘Was it the Punishment Battalion?’ They’d been together many times since Pauli had served his sentence, but until now the Punishment Battalion had been a taboo subject.

‘Changed in what way?’

‘You’re tougher, more determined. In the old days you wouldn’t have come looking for trouble. You’d have let a fellow such as Esser fend for himself.’

‘The Punishment Battalion was nothing. It was a relief to get away from that pig Brand. Sometimes I pitied you for still having to endure the brute.’

‘But they sent you into all the hardest fighting.’

‘It wasn’t so bad. It made a man of me. I learned how to survive – survive when all the odds were against survival, survive when all around me were dying.’

‘And after that you went to serve in a Sturmbataillon. Tell me about that. Was it like the Punishment Battalion?’

‘It was like nothing you’ve ever seen. With more such units we would have won, Alex.’

‘It wasn’t the lack of storm battalions, Pauli. It was these damned civilians who stabbed us in the back. As an officer I remain loyal to the government, but it’s hard to forget that these politicians we take orders from are the cowards and socialists who railed against the army all through the war….’ He stopped; even now his officer training inhibited him against such outbursts, ‘But tell me about the storm battalion.’

‘No rifles: carbines, and lightweight machine pistols, and small flame throwers. Everything was designed for lightness and fast movement. Even the other ranks got pistols. Special uniforms, leather pads on elbows and knees. No cartridge pouches – we stuffed rounds into our pockets. Round our necks we carried bags of grenades. We were unstoppable …and ruthless.’

‘They took you as a Stosstruppführer.’