По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

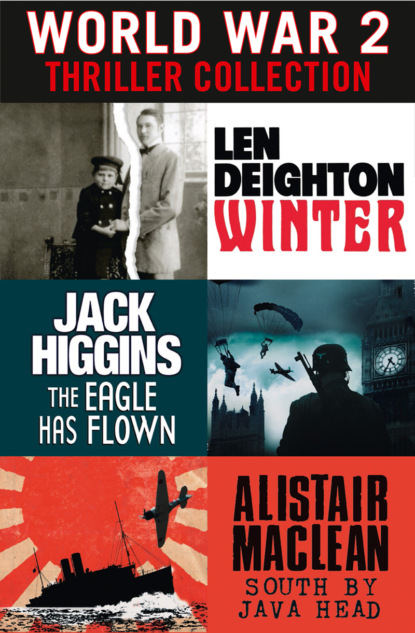

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘And my stepmother won’t be so crazy about having to share Dad.’

‘I’m sure you’re wrong,’ said Veronica.

‘No, I know her too well. She loves me and I love her, but every letter she writes says how pleased she is that I’m settling down here.’

‘What about your father?’

‘I’d like to go and see Dad, but a visit would be enough. A visit over January, February and March, when the weather is so terrible here.’

‘And what about Peter?’

‘I don’t want to influence him one way or the other. It’s his life: his career. And all the more difficult when a family business is involved.’

‘His father wouldn’t disinherit him, Lottie.’

‘Now, don’t get me wrong, Mrs Winter. Money doesn’t enter into it, but I reckon that a wife, if she’s smart, doesn’t give her husband advice about his career. Because if things go wrong she is likely to get all the blame. Men are like that; at least I figure they are.’

‘I’m afraid men are like that, Lottie.’

The maid came in. Veronica had recently changed all the servants’ uniforms so that they were no longer in ankle-length skirts. This parlourmaid had a fashionably short black dress with a superb lace apron and cap. Lottie decided that her servants should be similarly modernized.

It was the complete silver tea service. Even though the two women knew that neither of their husbands would join them, plates, teacups and cutlery were set for four, as always. As well as the traditional German plum tart there were brownies. Ever since the first tea they’d had together Veronica always tried to arrange to have some American cookies or pastries prepared for Lottie. It had become a treat that they both looked forward to, a calculated touch of nostalgia.

When the parlourmaid had poured tea, offered the neatly cut thin bread and butter, and departed with a curtsy, Veronica turned to her guest and said, ‘What is it, Lottie? I feel there’s something else bothering you. Is there something wrong between you and Peter? Would it help you to talk about it?’

‘Oh, Mrs Winter!’

‘I do wish you’d call me Veronica.’

‘Oh, Veronica,’ she said. Tears welled up in her eyes. ‘You’ve been so wonderful.’

‘Lottie, darling, what is it?’

‘I’m pregnant.’

‘Are you certain?’

‘I’m certain.’

‘Have you told Peter?’

‘You’re the first person I’ve told.’

‘It’s nothing to cry about, Lottie darling. It’s something to celebrate.’ Lottie continued to cry; the tears rolled down her face, and she didn’t even try to dab them away. Veronica searched for something else to say: ‘And Peter will be overjoyed. He certainly won’t take the job in California at a time like this. It would be too much for you … unless they’ll wait a year.’

‘They won’t wait,’ said Lottie, drying her eyes with a tiny lace handkerchief. ‘The position has to be filled by the end of January; they specially stipulated that.’

‘Peter wouldn’t go there alone. He wouldn’t leave you. I know he wouldn’t, and I’d forbid it anyway.’

Lottie sobbed more until she was gasping for breath. Veronica put her arms round the young woman to comfort her. ‘Lottie darling, you must pull yourself together. Sit back. Blow your nose, and have some tea.’

‘He’ll turn down the job,’ said Lottie after she’d had a few moments to recover. ‘Peter will turn down the job, on account of the baby. Then he’ll blame me forever afterwards.’

‘You silly child. Of course he won’t. He’ll be the happiest man in the world.’

‘Do you really think so?’

‘Of course he will. And he’ll be a marvellous father. You must tell him your news as soon as he arrives – I’ll leave you together for a few moments – and we must get a cable off to your father and to my father, too. Everyone is going to be so excited at the news.’

1927

‘That’s all they ask in return’

It was late May, a time when all Berlin is filled with the smell of linden flowers. The sun came spasmodically from behind ragged grey clouds, but it was not warm. Pauli sat outside to drink his tea and spend a few minutes watching the world pass by.

Pauli’s face was known in all the most fashionable cafés in Berlin: the Monopol, the Josty, the Schiller, the Café des Westens. But the one he liked best was opposite the Memorial Church: the Romanische Café. Some said this was the most famous café in the whole of Germany; others said it was the most famous in the whole world. Yet there was always room to sit down, for it could hold over a thousand people. It was open day and night and always busy: a place where intellectuals came to discuss philosophy, couples came to talk about love, others came to argue about politics, write letters or memoirs, review new plays or write poems. There were famous faces to be seen here. Up in the balcony, where the chessplayers liked to sit, one could often see Emanuel Lasker, who’d been world champion for thirty-three years.

Some of the clients were outrageous; at least they would have been had there been anyone left in Berlin who could feel outrage at the sight of shaved skulls, dyed hair, or flamboyant costumes. Outside in the street it was easier to be outraged by the sight of crippled ex-servicemen begging in their ragged uniforms, the painted faces of the homosexuals, or the pinched white faces of the child prostitutes.

Inside the café there were always pedlars going from table to table: shoelaces, matches, Literarische Welt, Die Rote Fahne, a copy of the Times from London four days old. An angry-looking young man offered crayon drawings. The drawings, too, were angry: jagged and spiky deformed servicemen, lewd matrons in suspender belts and black stockings, and bemedalled officers with porcine faces and no trousers. He stopped to show the drawings to two well-dressed Swedish tourists. They went through his wares solemnly and thoroughly but they did not buy. Tourists rarely did. Perhaps they didn’t want to take such things through the customs inspections. The young man offered the drawings at a cheaper price. The Swedish man shook his head, the woman laughed; the drawings were gathered up. Some said the young man merely sold the drawings; others said he was the artist. But no one knew the truth about it, just as no one knew the truth about anything in Berlin. It was better not to know.

There were newspapers hanging on sticks near the door. Pauli didn’t take the Nationalist Socialist paper – from its pristine condition he guessed that no one else had read it, either. He selected the Berliner Zeitung am Mittag, an undemanding tabloid, and sat down. His usual waitress brought a glass of lemon tea and schnapps. He always came here for tea after the lunch of sandwiches that he ate at his desk. He usually sat here for thirty minutes before returning to his office. It was the only way he got a break from work. All day long at his office people put their heads round the door: ‘I don’t want to interrupt you, Pauli, but…’

And the office had not got any better since the Nazis’ new Gauleiter, Josef Goebbels, had taken over Berlin. He was too damned enthusiastic, and the rank and file didn’t like the levy of three marks a month that he demanded from them. There were fewer than a thousand Nazi Party members in Berlin; it wasn’t the way to get recruits, and Goebbels’s Rhineland accent – which sounds funny to the ears of Berliners – hadn’t helped him. Strasser, the Regional Chief, opposed almost everything Goebbels suggested, and SA Leader Kurt Daluege – with his army of brownshirts – wouldn’t cooperate with either of them. With three bosses trying to run the Berlin office, very little got completed, but there was no way that any of them would listen to Pauli Winter’s suggestions. Especially when – as Goebbels reminded him – he’d not even bothered to join the party.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: