По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

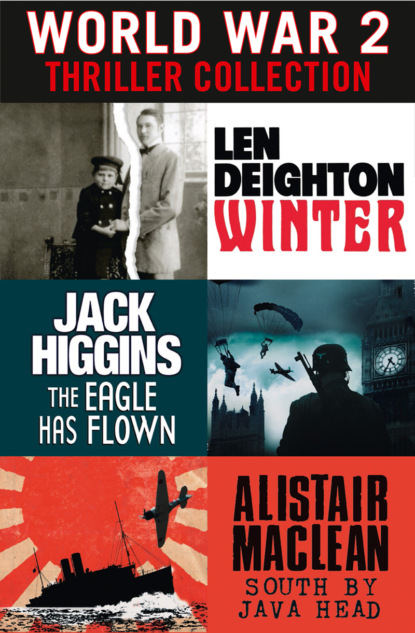

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Your father sent for him. I was there. Is something wrong?’

‘Pauli invited some strange people.’

‘Sure, but it’s his show.’

‘His birthday? Yes, but sometimes one’s friends do not mix well with family.’

‘Will he get told off?’

‘He’ll get round it. Pauli can charm his way out of anything,’ said Peter.

‘Do I hear a note of envy?’

‘No.’ Peter smiled. How could he ever envy Pauli, except sometimes for the way that his parents indulged him? ‘He’s always getting into the sort of scrapes that test his charm to the very limit. Goodness knows how he’ll ever pass his law finals.’

‘I can’t imagine your brother, Pauli, as a lawyer.’

‘And what about me?’

‘Easily…a trial lawyer, perhaps. You have the style for that.’

‘And Pauli doesn’t?’

She was cautious. Peter’s readiness to defend his brother against any sort of criticism was something of which the Wisliceny girls had already told her. ‘Is there any need for him to do anything? Isn’t it enough that he’ll inherit half the Winter fortune and keep this fine old house going while you run the business?’

Peter smiled grimly. ‘Father would have something to say about that. Father is a man of the Kaiserzeit…. So, I suppose, am I.’

‘Yes, you are.’

‘And you don’t object to us formal, humourless Teutons?’

‘Object? Goodness, what could I object to? I’m not going to marry and settle down here. I’m just a tourist.’

He hastily thought of something to say. ‘Pauli’s not a fool. He’s clever, and as brave as a lion.’

‘Poor butterfly…’ she sang softly as they danced. She knew the words, and her soft, low, murmuring voice was bewitching.

‘Keep your money’

Pauli loved and feared his father, but now the time had come for him to speak up for himself or be crushed by his father’s personality. He looked at the picture of the Kaiser that hung on the wall, and then he caught his breath and turned on his father. ‘You pretend it’s a party for me, but who are invited to your grand house? Your rich friends and the people you want to impress, that’s who. Do you know what I think about your friends and your party…?’ He stopped. His mother’s face had turned pale, and there was a look of such anguish there that he could not bear to hurt her more. Through the door he could hear the band playing ‘Poor Butterfly’. It took him back to the first day of the 1918 offensive – the captured British battery, the tinny gramophone.

‘Go on,’ said Harald Winter calmly. Deeply hurt by his son’s outburst, he couldn’t repress a secret feeling of satisfaction that Veronica was present to see his predictions come true. For Harald more than once had said that Pauli was an ungrateful wretch. It was his terrible experiences in the war, of course. Harald Winter had always been quick to explain the faults of those around him. Pauli had been through all sorts of hell, and that had affected him. Otherwise the boy would have been pleased to have such a lavish celebration held in his honour. As for Pauli’s complaint that most of the people there were friends of his parents rather than his own friends, he should have the sense to understand that this was his chance to get reacquainted with people who matter. And, anyway, a formal dinner of this scale was not something that his Freikorps rowdies, or his noisy, loose-living student friends, would appreciate. Judging by what Winter heard at his club, the whole party would have become an orgy inside ten minutes.

Harald Winter told his son, ‘Captain Graf was invited at your insistence, as I understand it. How do you explain his disgraceful criminal conduct?’

‘I fought alongside Graf, and many others like him. They fought the communists, and are still fighting them, to keep Germany safe for you and others like you. Who are you to sit in judgement on him? What did you do in the war except make money?’

‘I haven’t noticed that you decline the chance to spend a portion of it. You have a generous allowance, a motorcycle … your college fees, books, you run up bills at my tailor.’ Harald stopped, choked with indignation and anger.

‘Keep your money….’

‘No, Pauli, no. Say nothing that you’ll regret tomorrow,’ his mother pleaded.

‘What loyalty do you show to your friends?’ persisted Pauli. ‘Tonight you’ve invited all your aristocratic Russian refugee friends: princes, dukes and duchesses, and even that old fool who claims to be a nephew of the Tsar. Do they know that aircraft built in your factories are helping to train the Red Army that kicked them off their grand estates?’

‘The army don’t ask my advice about where to use their aircraft,’ said Harald Winter calmly.

‘I can’t continue living in this house,’ said Pauli. ‘I should never have moved back here. It’s stifling, constricting, like a prison, like a museum.’ To his mother he said softly, ‘It’s better that I go, Mama: We live in such different worlds. You hate my friends and I have grown to hate your values.’

‘Decency and respect? What values are you talking about?’ said Harald Winter. ‘Poor Hauser was stabbed by that madman Graf. Your friend Esser has drunk so much that he vomited on the morning-room carpet and knocked over a caseful of chinaware. How dare you tell me that you hate my friends and my values?’

Pauli shrugged. It was always like this when he was dragged into a row; he found himself arguing to support issues in which he didn’t believe. He loved Hauser and despised Graf, but that didn’t change the fact that his father’s world was an ancient, alien place from which he must escape. ‘I’m sorry, Papa. Forgive me, but it’s better that I leave. I will go to Hamburg or Munich or somewhere I can start again. I would never have got through my finals anyway. I am too stupid to study the law. But Peter will fulfil your hopes and expectations.’

‘Pauli…’ said his mother.

‘Let him go,’ said Harald Winter. ‘He’ll be back when the money runs out. I’ve heard it all before. Let him discover what it’s like to be a penniless beggar in these terrible times. He’ll be back knocking at the door before the month is out.’

Veronica said nothing. She did not believe that Pauli would come back begging for his father’s help. And, in fact, neither did his father.

In the event, Pauli did move his effects from the house, but he didn’t go to Hamburg or Munich. He moved into a room in the nearby district of Wedding in a boardinghouse run by a war widow, an intimate friend of Fritz Esser. Pauli declined to take any more payments from his father, but he did not give up his law studies.

It was Peter who spent hours pleading his brother’s case. It was Peter who reminded his father of the terrible time Pauli had had in the war, and Peter who conspired with his mother so that the approaches were made when Harald was in a good mood.

Although Pauli took no more money from his father, his brother, Peter, transferred money to his bank account each month. Pauli’s parents accepted this covert financial arrangement, and honour was satisfied. Pauli was happy to feel that he wasn’t accepting money from his father, while his father was happy to know that in fact he was. And, as Harald Winter remarked to his wife, he didn’t want Pauli to be driven to such a state of penury that he sold that house on the Obersalzberg.

Most important, Pauli got permission from the university to switch, starting the following term, from company law to criminal law. It was a study that Pauli found immediately interesting and relevant. To everyone’s surprise, not least to Pauli’s, he caught up quickly with his fellow students and came fifth from the top in his exams.

Coaching Fritz Esser in this subject was less successful, although with a great deal of effort Fritz got through his interim exams before abandoning his studies. One day, he promised, he’d go back and get his law degree. But meanwhile he’d become a full-time paid official of the Nazi Party and wholly occupied with politics.

Soon after Pauli left home, his uncle Glenn Rensselaer found his shabby lodging. Glenn was working for some American office-machinery company that had its main agency in Leipzig. He came often to Berlin and always brought Pauli presents. Pauli liked Glenn; he liked the way he came up to the top-floor garret room and did not stare around at the cracked lino, the newspaper pasted on the broken windowpanes to provide a modicum of privacy, the chamberpot under the bed, or the unshaded light bulb. Glenn seemed perfectly at home in the rat-infested tenement. The occasion of his arrival was usually marked by Glenn’s presenting the landlady and certain other tenants with bottles of schnapps. Glenn said he got them cheap, but Pauli knew he paid full price at the shop round the corner. Glenn was like that.

When Pauli passed his final exams, it was Glenn who persuaded Harald to attend the ceremony, and Glenn who arranged dinner for twenty-four people at Medvedj, a smart restaurant on Bayreuther Strasse, and footed the bill for blinis and caviar, borscht and kulibiaki, a gypsy trio, and all the trimmings in this fashionable restaurant where Berlin’s Russian exiles liked to go when they could afford it. And when Glenn asked so casually what Pauli would do next, and Pauli gave a long, involved explanation about a company that had offered to provide him with an office and secretarial help on condition that he do some legal work for them, Glenn’s congratulations sounded warm and sincere. But Glenn Rensselaer was no fool, and he guessed just as quickly as did Peter and Harald Winter that the ‘company’ that was to play fairy godmother was the Nazi Party, and that Pauli was going to be defending some of the worst thugs involved in the streetfighting, assaults, and murders that had become a regular part of the German political scene.

When, the following October, Peter talked about becoming engaged to Lottie Danziger, Glenn Rensselaer gave Lottie a jade brooch bearing Peter’s initials on the gold setting and gave Peter a watch engraved with the date of their intended engagement party. ‘Now,’ Glenn Rensselaer told them both, ‘you’ll have to go ahead.’ And they did. It was another big party, this time at the Wisliceny house. Lottie’s parents did not come. They had long before decided that Lottie was going to marry the eldest son of a West Coast oil tycoon, and they were angry to think of Lottie’s marrying Peter Winter, a German. ‘Not so angry as I am,’ said Harald Winter to his wife the night he first heard the news: and many many times afterwards. ‘I don’t know what appals me more,’ he said, ‘the thought of him married to an American or to a Jew.’

His wife did not take this insult personally. During the war she had grown used to hearing her countrymen denigrated and insulted. Calmly she said, ‘How can you say that, when the Fischers are such close friends?’

‘The Fischers are different.’

‘And Peter and Lottie plan to live in Germany. Think of her poor parents – six thousand miles away – they are losing her forever.’ It was an expression of Veronica’s guilt. Now, as her father grew old, she thought about him more and more.

Harald Winter grunted. He felt not at all grateful to fate or to the girl. Of course they would remain in Germany. Peter hadn’t taken complete leave of his senses, thank God.

1925

‘You don’t have to be a mathematician’

‘Explain?’ said Glenn Rensselaer. ‘I can’t explain it any better than I have there in the written report.’ The bald-headed young American behind the desk looked at him blankly. Glenn Rensselaer went on: ‘I guess you mean describe it in terms of its U.S. equivalents. Well, I can’t do that, either. These Freikorps groups are just bands of armed men in makeshift uniforms. Usually their commanders are captains or majors, sometimes a colonel, and, rarely, a sergeant. They take their orders from whoever pays them, and sometimes they don’t even obey their paymasters. Some of the officers behave like gangsters; some of the rankers are professional criminals. But some of these men are patriots and idealists. It’s impossible to generalize about the Freikorps except to say – thank God – there is nothing in the U.S. that I can compare them to.’