По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

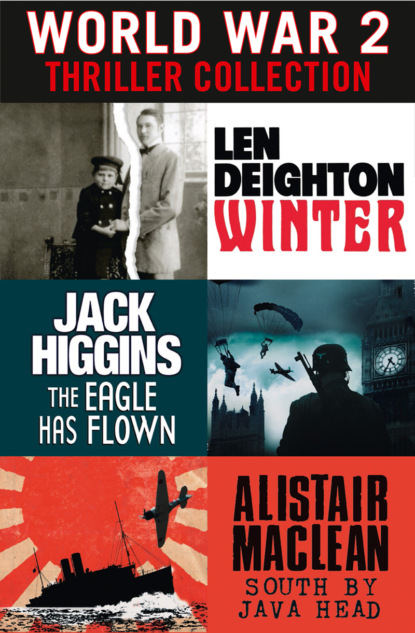

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘The Englishman? The spy?’

‘He was no spy. That was just Papa’s way of attacking him.’

‘Are you saying that Mama had a love affair with the Englishman and that Papa knew about it?’

‘I found his wristwatch under Mama’s bed….’ There, he’d said it. A thousand times it had been on the tip of Pauli’s tongue to reveal the secret, but now he’d said it. And now he regretted it.

Peter closed his eyes. ‘It’s incredible,’ he said at last.

‘Incredible or not, it’s true. I think Mama was afraid I would blurt out something that would betray her secret.’

‘But you never did?’

‘I didn’t understand the significance of finding the watch there until years later. But then, when Mama took the chloroform in the summer of 1914, and Frau Wisliceny came round to look after her…That night, when I went in to kiss Papa good night, I noticed that he was piecing together torn fragments of a letter. It must have been a letter to Mama from the Englishman.’

‘I wish you hadn’t told me,’ said Peter. ‘I feel besmirched by it.’

‘Don’t be absurd,’ said Pauli. ‘Does Mama have no right to be with someone who loves her?’

‘She has Father.’

‘And Father has half a dozen other women. He has no real, deep love for Mama. Sometimes I think he might have married her only for the Rensselaer money.’

Peter was affronted. He could hardly believe that Pauli had changed so much. Pauli had always been in awe of father. ‘If you were not my brother I’d call you out for saying that.’

‘A duel?’ Pauli laughed. ‘You think I’d care about losing my life in a duel? Where I am, I see men maimed and dying every day. I stood next to a sentry last week while a shell splinter trepanned him. His brains spattered into my face. You complain about my dirty uniform. Do you know what the stains on my jacket are? Blood; the blood of boys who forget to lower their head at the right time, or make too much noise mending the wire at night. Would you like to know about the stains on my trousers, Peter? Faeces! I shit myself with fear every time I hear the whistle of a mortar bomb or shell, or hear at night the movement of a few rats, which might in reality be a British raiding party coming to bury a trench knife in my throat. It’s quick and quiet, the throat, you see. You learn how to cut a man’s throat while holding a hand very tightly over his mouth so that he doesn’t scream.’

‘You did this, Pauli?’ His elder brother’s eyes were wide and his face had gone pale. ‘Killed with a knife?’

‘Half a dozen times. I have a superior officer – a contemptible cad – who thinks young Lichterfelde graduates like me should be exposed to maximum danger. He tells us that. He also told me that I mustn’t come here today. I suppose that shocks you, too. I came here today – in this dirty uniform of which you so disapprove – having defied the lawful orders of a superior officer. And I shall do it again whenever it suits me.’

‘You are insane, Pauli.’

‘No, I’m not insane, but sometimes I think His Majesty must be insane to continue with this mad war.’

‘Pauli, you must see a doctor. You are insane.’ Peter looked round fearfully, astounded to hear such treasonable talk from his young brother.

‘Perhaps you’re right. Then come to the front line with me, Peter, and perhaps you’ll become insane, too. But I promise that you’ll lose all fears of death, disgrace or anything else that fate has waiting for us.’ Pauli reached forward to take the glass of schnapps that the captain had sent to them, and he downed it in one swallow.

When Peter spoke again, his voice was soft and low, his tone more conciliatory. ‘Whatever may be the truth of it, Pauli, I beg you, for your own sake and for that of the family, to leave such thoughts unspoken. It can be very dangerous. People might even think you are mixed up with these crackpot radical groups who are so outspoken against the war.’

‘After this war I want things to be different, very different, but I’m not a Spartacist, if that’s what you mean.’

‘I know you’re not. That man Liebknecht is a traitor and a swine. It’s a good thing he’s gone to prison. But now the Tsar’s been deposed, everyone who says anything against the war is lumped together with the revolutionaries. In the North Sea Fleet we have already had some serious insubordination, bordering on mutiny. The admiral jumped on it vigorously, I’m glad to say. I was sent to Wilhelmshaven with the legal team. Do you know who I saw there? Fritz Esser.’

‘Fritz? That rogue.’ Pauli laughed. ‘Was he the ringleader? With all his hero-worshipping talk about his precious Karl Liebknecht, I wonder how the navy ever accepted him.’

‘If he was the ringleader he was too cunning to be caught. He’s found himself some soft job in the supply branch and is already a petty officer.’

‘A petty officer. I thought he was illiterate.’

‘Esser? Of course not, Pauli. Can’t you remember all those books and pamphlets he’d read about the coming revolution?’

‘Yes, you’re right.’

‘You thought the world of him.’

‘We both did,’ said Pauli, ‘but we laughed at him too.’

‘I’m not laughing now, Pauli. Esser and his ilk are dangerous men. Make no mistake, Germany has many such uneducated, treacherous fools, who will sell out their country if they get the chance.’

‘Sell out their country? To what?’

‘I don’t know…they don’t know, either …some fantasy about a world revolution and the brotherhood of mankind. They want power, Pauli. I saw these people at close hand when we were preparing the court-martial evidence in Wilhelmshaven. Many of them were simple men – stokers mostly – but among them were some trained agitators, well equipped to argue their crackpot political theory with lawyers, or anyone else.’

‘It’s all finished now?’

Peter glanced round nervously. ‘No, it’s not finished, I’m afraid. We put a few troublemakers behind bars, but there are too many Essers at large. Back home, civilians are working regular twelve-hour days and food is very short, thanks to the British naval blockade. So many tired and hungry workers provide opportunities for rabble-rousers. Unless conditions improve soon, I’m afraid we’ll see more and more trouble from servicemen and civilians.’

‘I’ve never heard anything of this before, Peter.’

‘I didn’t intend to talk about it.’

‘We don’t hear anything at the front.’

‘This revolution in Russia will give Liebknecht and the Rosa Luxemburg woman encouragement to renew their efforts. The radicals will bide their time, and when they make their bid for power they’ll be ready to spill blood. Not only their own blood, either!’

The two of them sat for several minutes, looking at each other and drinking the delicious coffee that was available to these lucky men who fought their war behind desks. Then there were loud voices in the corridor, the sort of anxious exchanges seldom heard in these quiet corridors. Suddenly the door opened and the staff captain came in, looking agitated. With no more than a nod to the two officers, he grabbed papers from a tray on his desk and retrieved others from the top of a cabinet. ‘The Americans have declared war,’ he said over his shoulder as he sorted through his papers.

‘Are you sure?’ asked Peter. It was impossible to take in. America was thousands of miles away, and their army was negligible. Even if their army was enlarged, the U boats would make sure the Americans never got to Europe.

‘The American Congress ratified it yesterday. What a thing to happen at Eastertime!’ He threw papers into a file. ‘Do you realize what it means?’

‘Will they send armies to Europe?’ said Pauli. Already they were stretched to the limit to hold the front.

The captain said, ‘We must disengage from the Russians and crush the French with one quick, massive offensive before the Americans arrive.’ It sounded like something he’d been told.

‘Is such a thing possible?’ said Peter.

‘We will discover in good time,’ said the captain. He dropped a handful of papers against the desktop to get them straightened. ‘If we haven’t won the war by Christmas, it will be the end of the Fatherland. The end of everything we’re fighting for.’ Peter looked at the staff officer and was disturbed by his demeanour. Perhaps the Americans would make a difference. There were so many of them, and their resources were limitless.

As the captain went out through the door, Pauli could see, at the top of the grand staircase, the general who commanded the division and two aides. They were magnificently attired: swords, Pickelhauben, gleaming boots, and chestfuls of orders and decorations. He got only the briefest glimpse of the three men, but all his life Pauli remembered the scene in every small detail, even the way in which the general was holding his Turkish cigarette in a jade holder.

The two brothers had not resumed their conversation when they heard the distant explosion of an enemy shell. The rumble of gunfire had been a background to their talk, but this one was nearer, about three miles away. They went to the window in time to see the plume of brown smoke that marked its fall. By that time another shellburst shook the glass. The second round landed only slightly closer.

Peter said, ‘It’s the first time I’ve been on the receiving end of it.’

‘A heavy-calibre gun,’ said Pauli. ‘Somewhere up there a couple of men in an observation plane are trying to locate us. I don’t know why they find it so difficult: a big mansion like this with two big spires.’