По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

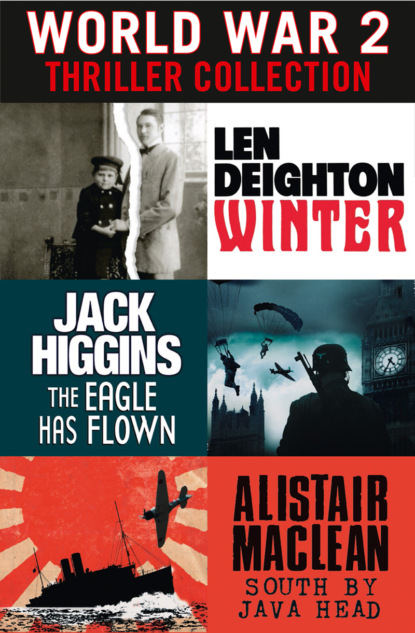

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He smiled. ‘I have persuaded the navy that airships made of wood and glue are not suitable for use over the sea in bad weather.’

‘You think only of money!’ she said.

He released her arm and said softly, ‘How can you say that, you little bitch, when I have two sons fighting for us?’

‘I’m sorry, Harry. I didn’t mean it.’

He gently pulled the silk negligee from her shoulders so that he could look at her pale body. ‘You are exquisite, darling Martha. All is forgiven in your embrace.’ It was the frivolous, supercilious manner he adopted for their bouts of lovemaking. It was a way of avoiding any serious discussion.

But as he reached for her there was a knock at the bedroom door. Martha twisted away from his hand and, pulling her dressing gown tight, went to the door.

It was her maidservant. He couldn’t hear what was said. Despite reassurances from his physician, he was convinced that he was growing deaf.

‘What is it?’ he said as she returned to the bed. ‘Come back to bed, my little tiger.’ But she remained where she was, a petite, pale figure, her face forlorn, with jet-black hair tumbling over her eyes till she pushed it back with her small, perfect hands.

‘The zeppelins over England last night…five didn’t return. Your son Peter…’ She couldn’t go on. Tears filled her eyes.

‘My Peter…What?’ He got out of bed, and went to her and held her. She was sobbing. ‘My poor Harry,’ she said.

It was almost noon next day when Peter started to regain his senses. Even before he tried to open his eyes, he smelled the ether in his nostrils. The hospital room was filled with yellow light: the sun coming through a lowered blind. When he moved his feet – an exploratory movement to discover if he was all in one piece – he felt the stiffly starched sheets against his toes. It was only then that he realized he was not alone in the hospital room. Two men in white coats were standing near the window, looking down at a clipboard.

‘…the only one to escape from the forward gondola,’ said one voice.

‘And completely unharmed, you say?’

‘Just scratches, bruises, and the finger.’

‘Did he lose the finger?’

‘No, he had the luck of the devil. I just removed the tip of it.’

‘And it was the left hand, too; well, I can’t imagine that that will make a scrap of difference to any young chap.’

‘Unless he was a pianist…’

‘And the pianist – Hennig, isn’t it? – was the one with the broken ankle. God moves in strange ways; I’ve always said that.’

‘It’s a curious war, isn’t it? The zeppelin staff plan to bomb Saint-Omer’s town hall when all the top Allied military commanders are there together with the King of England and the Belgian King. And the Kaiser forbids it.’

‘You disagree?’

‘After a night looking at the cruelly mutilated bodies of so many very young men, I simply say it’s a curious war.’

Peter heard one of them hang the clipboard back on its book before they went out of his room, but he kept his eyes closed and pretended to be asleep.

In England the next day, visitors went to the wreckage of the zeppelin that had been shot down near London. Frederick William Wile – one time Berlin correspondent of The Daily Mail – wrote ‘…even those who felt most bitterly about the brutality of raids upon unarmed civilian populations could not refrain from pity at the sight.’

Wile continued: ‘It is one of the traditions of the Hohenzollerns that the King of Prussia must ride across the battlefields on which his soldiers have fallen and look his dead men in the face. Trench warfare and a decent regard for his own skin have prevented William II from carrying out this ghoulish rite in his war. But I wish some cruel Fate might have taken the Kaiser by his trembling hand yesterday morning and led him to that rain-soaked meadow in Hertfordshire, and bade him look as I looked at the charred remains of human wreckage which a few hours before was the crew of an Imperial German airship. I wish Count Zeppelin, the creator of the particular brand of Kultur which sent the baby-killers to their doom, might have been in the Supreme War Lord’s entourage. I wondered, standing there by the side of that miserable heap of exposed skulls, stumps of arms and legs, shattered bones and scorched flesh, whether the Kaiser would have revoked the vow he spoke at Donau-Eschingen in the Black Forest eight years ago when he christened the inventor of airship frightfulness, “the greatest German of the twentieth century”.’

1917

‘Not so loud, voices carry in the night’

Paul Winter had been called ‘little Pauli’ for so much of his life that, now seventeen-years old, he still thought of himself in that way. He had the cherubic face that made some lucky men youthful and attractive all their lives. Some of the others called him ‘Lucky’. So what rotten luck that a member of the Prussian Officer Corps on active service on the Western Front should be attached to this wretched Royal Bavarian infantry regiment. What was ‘little Pauli’ doing sitting in this deep dugout on the Western Front, listening to the muffled thumps of enemy shells exploding? The morning bombardment had started with the adjoining sector, but now they were landing closer and closer. He tried to push the fears out of his mind and concentrate upon writing a letter to his parents. The dugout was dark; he had only the light of one flickering candle. He used a penknife to sharpen the stub of his indelible pencil, and he gave a deep sigh.

But this introspection didn’t mean that he felt in any way sorry for himself. The last remnants of self-pity had been eliminated during his years at the cadet school. Pauli accepted life day by day as it came but that didn’t mean that he never asked himself why his life had for so long consisted of spartan food, strict discipline, and so little rest. A regime to which had lately been added gluey mud, mortal danger, and long periods of boredom. Pauli was at heart an easy-going, pleasure-loving fellow who wanted only to live and let live.

My dearest parents,

Thank you for the parcel. It arrived safely. It was so kind of Cook to knit the socks for me, but they are very big – two sizes too big. No matter, one of the other men will benefit. I shared the tin of meat with only my friend Alex but we had a little party to eat all the other food. You must not worry about me. I am many miles away from where the real fighting is taking place. Most of the time I am in Headquarters and cannot even hear the artillery fire

He stopped writing. Perhaps that was going too far. Even back in Brussels they could hear the artillery fire, and his parents might well know that. He added:

except when the wind blows from the west. Peter is coming to see me today. I will have lunch with him at Headquarters.

He wondered what to say next. Several times reduced almost to despair by the cold, filth, mud and cruel loss of friends, he’d attempted to write a letter that truthfully described what it was like here. But each time he’d abandoned the effort and scribbled the same sort of reassuring banalities that everyone else sent home to keep the family ignorant and happy. So he wrote:

The weather here is good for this time of year and the war is going well for us. I must end this letter now. It is very early in the morning and I have a lot to do.

I will write again – a longer letter – after Peter’s visit,

Your loving son,

Carefully he signed it and read it again before he put it into an envelope. He was always promising ‘a longer letter’ but he never wrote longer letters, just short thank-you notes. Though he wrote wonderful letters in his mind, he never got them on paper. He felt constantly guilty about neglecting his parents. He knew how much they liked to hear from him and how much they worried all the time. Did all sons feel such guilt about their relationship with their parents? Most specifically, did his brother, Peter, feel guilty about his relationship with them? He knew the answer to that even before asking the question. Peter didn’t neglect them. He wrote a long informative letter to them every week. Pauli had seen the letters piled up high on his father’s desk. They read them again and again. And yet he knew that they didn’t worry about Peter as they did about him, especially since Peter was taken off flying duties after the crash. Since Christmas 1916 Peter had been assigned to liaison duties in Brussels, and his life was no more dangerous than it would be at home in Berlin. Here on the front line, life was more hazardous; the regiment had lost fourteen officers in five weeks, five dead and nine wounded. From his pocket he took the postcard that Peter had sent arranging their meeting. For the thousandth time he made sure he had the date, time, and place right. He put the postcard away again with other cards from Peter that made a bundle so thick he couldn’t button his breast pocket over them. Ever since cadet school, Peter had sent postcards regularly: every two weeks, never more than three. Sometimes it was no more than a sentence – a joke, a greeting, a memory from the past, one of their nanny’s oft-repeated Scottish aphorisms. How did Peter know how important the cards were to him? Pauli never told him and never even responded to them. Peter, Peter, Peter. How he missed him.

‘Runner!’ The command was that of a Prussian officer. Pauli was always a little surprised to hear the voice coming from himself.

‘Herr Leutnant?’ The man almost fell down the steps and into the dugout. He was typical of the farm boys that made up most of the regiment. The rest of them were older men with families or physical disabilities that had kept them out of the war until last year, when the casualties meant that more and more men were needed. They were only half trained. The regiment should not be holding a section of the line: it should be at a training camp, where these fellows could learn to march and shoot. On the ranges, half of them couldn’t even hit the target, let alone score. The machine-gun teams were pitifully slow at stripping the guns or even at clearing them when they jammed. If the British infantry decided to attack on this sector, they would be able to walk through. Or at least that’s the way it appeared to those who hadn’t seen the state of the British soldiers facing them. But Pauli had spoken with enough British prisoners to know that the winter of endless rain, and the waterlogged trenches, had brought enemy morale down to a point where some Tommies were thankful for the prospect of a dry POW camp away from the fighting.

The theory held by the generals at Imperial Army HQ was that a few experienced NCOs and some trained Prussian officers for each company would work a miraculous transformation in this fighting force, but of course it wouldn’t. The ‘trained Prussian officers’ were no better than boys from cadet schools, some with less training than Pauli. And as for the experienced NCOs, they were too damned experienced. They were disillusioned veterans, many of them only recently discharged from hospital, men who had hoped to spend the rest of the war in safe jobs with training units. Now they were back in the front line, but instead of being with their comrades, they were wet-nursing this raggle-taggle bunch of stupid peasants, some of them not even Bavarians, kids with incomprehensible Austrian accents or unpronounceable Hungarian names. No wonder there were mutterings of discontent, Marxist leaflets, and every now and again, a wound that looked suspiciously like something that might have been self-inflicted.

He put the letter into an oilskin pouch to protect it from the mud, the rain and the runner’s filthy hands. ‘Take this letter to regimental Headquarters and tell the clerk to put it with the officers’ mail so that it goes off this morning. Do you understand?’ There was a crash that made the candle flicker and some dried pieces of mud fell from the lintels overhead. ‘That’s not very close: the other side of the railway lines … even farther, perhaps.’ It was an automatic reaction, done always to reassure whoever was nearby. Pauli buttoned his precious stub of indelible pencil into his jacket.

‘Yes, Herr Leutnant.’ The boy didn’t believe it, of course; the runners got about and knew what was happening. The British artillery were softening up the communications trenches so that no reserves would get here when they attacked. Rumours said that it would come in two or three days’ time. Lots of British patrolling lately – that was usually a sign of an impending attack. Pauli knew all about it because he was the only officer in the regiment who spoke fluent English. He was called upon to interrogate the prisoners or sort through the personal effects of the British dead before the things were sent back to the intelligence officers. Two days, three at the most. A sergeant from the South Wales Borderers had virtually admitted it to him.

The soldier took the oilskin packet and stumbled over his rifle butt, striking his helmet against the low doorway as he hurried up the steps and out along the trench. Pauli watched him without comment: Pauli, too, was inherently clumsy. He, too, stumbled up the steps more times than not. Why were some people like that, no matter how hard they tried. Pauli would have loved to be adroit and elegant, but he couldn’t even dance without stepping upon his partner’s feet.

As the antigas flap on the door swung back, a heavy smell of fresh cordite and the stink of the latrine buckets came into the dugout. Oh well, it was a change from the steady smell of unwashed bodies and putrefaction that was the normal atmosphere down here.

‘What’s the time?’ From one of the wooden bunks built into the far wall a figure swung his legs to the floor and then slowly emerged from the blanket that cocooned him. Alex Horner – Pauli’s close friend at the cadet school – had found himself attached to the same regiment. Both boys had hoped to be assigned to one of the better Prussian units – cavalry, guards, or dragoons – instead of this collection of conscripts. But they were together, and that was the one consolation in the whole miserable, tormented existence they led.

‘Next time I’m in Wertheims department store, I’ll get you a watch with an illuminated face,’ said Pauli sarcastically.

‘Well, that might be a long time,’ said Alex. He rubbed his chin to decide whether he needed a shave badly enough for the company commander to admonish him. He decided to risk it: seventeen-year-old chins did not show much stubble per day. Leutnant Alex Horner was already acquiring the look of the Prussian officer. A duel at cadet school had left him with a sabre cut along his jaw, and the lice-infested conditions here on the front line required him to have his head almost shaved. But he was not yet the austere, unbending Prussian figure: he smiled too much, for one thing, and his nose was pert and upturned, the sort of nose more often to be seen on farmers’ daughters than on Prussian officers.

‘It’s three-thirty-two,’ said Pauli.

‘What a terrible time to be awake.’