По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

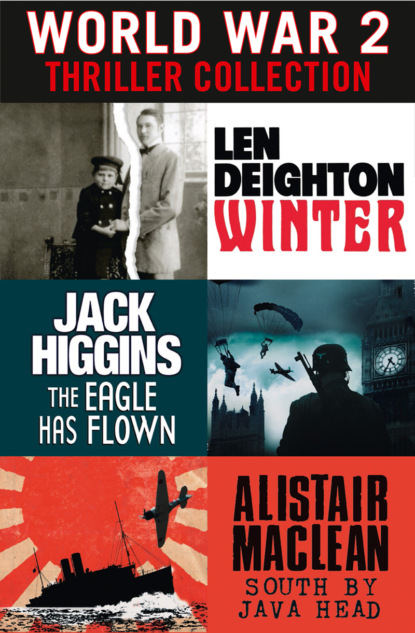

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘What’s that?’ Coloured flares lit the sky bright red.

‘They’re Very pistol lights. One of my boys telling the guns to stop firing while the airplanes try. Look at that zep go!’ Without bombs and water ballast, the zeppelin rose at an astonishing speed, so that the searchlights slid away and the airship disappeared into the dark night.

‘Has he escaped?’

‘Maybe. Somewhere up there two of them are playing a game of hide and seek. There’s a little scattered cloud to the north. If I was the zep captain I’d be making for it.’

‘And if you were the airplane pilot you’d be heading that way, too.’

They continued to stare towards the northeast. ‘It’s damned cold tonight,’ said Rensselaer senior. He shuddered.

Suddenly there was a red glow in the sky. Small at first; then, like a Chinese paper lantern, the great airship became a short red tube that lengthened as the flaming hydrogen burst from one gas cell to the next until the whole shape of the airship was depicted in dull red. Then at one place the flames ate through the fabric and were revealed as bright orange. Only then, as the aluminium melted, did the zeppelin cease its graceful forward motion. Halted, it became a cloud of burning gas around a tangle of almost white-hot metal, and then, slowly but with gathering speed, the great airship fell from the sky.

‘Oh my God!’ cried Rensselaer senior. No hatred now for friend or foe. He turned away and covered his face with his hands. ‘It’s horrible, horrible!’ Glen Rensselaer put his arms round his father’s shoulders and embraced him in the way that his father had so often comforted him as a child.

‘You’re a good, reliable officer’

On the wall of the office there was a calendar advertising ‘the margarine Germans enjoy’. It was there because some thoughtful printer had provided for each day a small diagram of the phases of the moon. The week before and the week after the new moon were marked in red ink. For the zeppelin service, knowing which nights were to be dark and moonless was a matter of life and death.

Lieutenant Peter Winter sat at the desk under the calendar. He wore the dark-blue uniform of the Imperial Navy complete with stiff wing collar that dug into his neck as he bent over his work. From this window, on those very rare moments when he looked up from his task, he could see the hard morning sunlight shining on the zeppelin sheds, the hydrogen plant and the flat landscape of the sort that he’d known as a child at Travemünde, not so far away.

‘Can I get the twelve-noon train, Peter?’ Hans-Jürgen, a fellow Berliner was today taking the despatch case to the ministry. If he caught the early train, he’d have a chance to see his girl.

‘Fifteen minutes, no more,’ promised Peter without looking up from his labour. When he’d volunteered for the Navy Airship Division, he’d never guessed how much of his time he’d spend at a desk, filling out forms and signing long reports about things he only half understood. Compared with this drudgery, working for his father would have been stimulating. On the other hand, working for his father would not have provided him with the naval officer’s uniform, of which he was secretly so proud, or the bombing trips over England, which he found both daunting and stimulating. Stimulating because he was at the period of physical and mental development when humans suddenly discover who and what they are. And Peter had discovered that he was courageous. The flights did not frighten him in the way that some of his comrades were frightened.

He signed the form and slapped it into the box while grabbing the next pile of paperwork. It seemed absurd that each zeppelin commander had to file seven copies of each flight log. Then came the route charts and endless lists showing the precise time that ballast was jettisoned and the exact amount of it. The weather forecast was compared with the actual weather conditions; the name, rank, number and age of each crew member had to be entered each time, and their behaviour throughout the mission noted. The times of take off, changes of course, bombing and landing were all here. Attached, on separate sheets submitted by the navigating officers, there were observations of enemy targets, and descriptions of any shipping seen en route. These had all been signed and then verified and countersigned by the commanders. All of it would soon be filed away and forgotten in some dusty Berlin office. Sometimes he felt like screaming and shovelling the whole pile of it into the wastepaper basket. But he plodded steadily on – with glances at the clock so as to have it all ready in time for his friend to catch the Berlin train.

There was no opportunity for Peter Winter to get to Berlin and see his girl, Lisl, the youngest of the Wisliceny girls – for tonight, according to the margarine calendar, was to be dark. And Peter was due to take off at 1:30 p.m. There would be no time for lunch.

And yet he must get to Berlin soon. Inge Wisliceny seemed to have some idea that she was his girl. He liked Inge, but only as a friend. It was her sister Lisl that he was seriously attracted to and this would have to be explained to Inge. Inge would be hurt; he knew that. Losing Peter to her young sister would be especially wounding, for Inge was rather haughty about her sisters. He didn’t look forward to it, but it would have to be done.

Inge was too serious, too conventional, and too intense. In some ways she was too much like Peter, though he’d never admit that. Lisl was young – childlike sometimes – irreverent, impudent and quite outrageous. But Lisl made him laugh. Lisl was someone he wanted to be with on his precious brief trips to Berlin.

The paperwork was only just completed in time for Peter to change into his heavy leather flying clothes, which came complete with long underwear. When he arrived at the airship, hot and sweaty, the engines were already being run up. Within the confines of the iron shed the noise was deafening. Their shed companion, an old zeppelin that dated from the first weeks of the war – her crew called her ‘the Dragon’ – was already out on the field.

‘Achtung! Stand clear of propellers!’ the duty officer in charge of the ground crew shouted. The engineers let in the clutches and engaged the gears. One by one the big Maybach engines took the weight of the four-bladed wooden props and the engines modulated to a lower note. A cloud of dust was kicked up from the floor of the shed.

Peter swung aboard and almost collided with men loading the bombs: four thousand pounds of high explosive and incendiaries. As he stepped aboard, the airship swayed and one of the handling party unhooked a sack of ballast from the side of the airship. Its weight approximated that of Peter so that the airship continued in its state of equilibrium within the shed.

He climbed into the control gondola, a tiny glass-sided room two yards wide and three yards long. The others were already in position, and there was little space to spare. Above the roar of the engines came the constant jingle of the engine room telegraph and the buzz of the telephones. The noise lessened as the engineers throttled back until the engines were just ticking over. Then they were switched off and it became unnaturally quiet.

The captain – a thirty-three-year-old Kapitänleutnant – nodded in response to Peter’s salute, but the rudder man and the man at the elevator did not look up. Hildmann, the observation officer – a veteran with goatee beard – immediately said, ‘Winter, go and take another look at the windsock. This damned wind is changing all the time…. No, it’s all right. Carl is doing it.’ And then, to the captain, he said, ‘All clear for leaving the shed.’ The observation officer then climbed down from the gondola in order to supervise the tricky task of walking the airship out of the shed.

There was the sound of whistles, and the command ‘Airship march!’ as the ground handling party tugged at the ropes and heaved at the handles on the fore and aft gondolas to run the airship out through the narrow shed door. Peter leaned out of the gondola and watched anxiously. The previous month, in just such a situation, the airship had brushed the doorway and suffered enough damage to be kept grounded. For that mistake their leave had been cancelled, and leave these days was precious to everyone. When the stern came out of the shed there was a murmur of relief.

‘Slip astern!’ The rearmost ropes were cast off, and she began to swing round so rapidly that the men of the handling party had to run to keep up with her. Then, with all the ground crew tugging at her, the airship stopped. Hildmann climbed back aboard and, with a quick look round, the captain gave the order to restart engines. In response to the ringing of the telegraphs, one after another the warmed engines roared into life. ‘Up!’ The handling party let go of the leading gondola and she reared up at an angle.

‘Stern engines full speed ahead!’

Now the handling party holding the handles along the rear gondola could not have held on to it without being pulled aloft. Suddenly the ship was airborne and every man aboard felt the deck swing free underfoot, and the airship wallowed in the warm afternoon air. It would be many hours before they’d feel solid ground underfoot.

The engineer officer saluted the captain before climbing the ladder from the control room up to the keel. His fur-lined boots disappeared through the dark rectangle in the ceiling. He was off to his position at the rear-engine gondola. He would spend the rest of the flight with his engines. The other men moved to take advantage of the extra space.

Now that the airship was well clear of the roofs of the sheds, the motors were revved up to full speed. There was no real hurry to reach the rendezvous spot in the cold air of the North Sea, but when so many zeppelins were flying together, it always became something of a race.

There were twenty-three in the crew. They knew one another very well by now. Apart from two of the engine mechanics and the sailmaker – whose job it was to repair leaks in the gas bags or outer envelope – they’d all trained and served together for some ten months. They’d flown out of Leipzig learning their airmanship on the old passenger zeppelins, including the famous Viktoria-Luise. They were happy days. But that was a long time ago. Now the war seemed to be a grim contest of endurance.

Oberleutnant Hildmann, the observation officer – who was also second in command – was a martinet who’d served many years with the Baltic Fleet. It was he who had assigned Peter to navigation. Actually this was the steersman’s job, but Peter’s effortless mental arithmetic gave him a great advantage when it came to working out endless triangles of velocity. It was a skill worth having when Headquarters radioed so many different wind speeds, and in the black night they tried to estimate their position over the darkened enemy landscape.

Peter had been given a sheltered corner of the chilly, windswept control gondola in which to spread his navigation charts. Now he scribbled the airship’s course and her estimated speed on a piece of paper, and tried to catch glimpses of the North German coast. Upon the map he would then draw a triangle, and from this get an idea of what winds the night would bring.

There was cumulus cloud to the north and a scattering of cirrus. The forecast said that there would be scattered clouds over eastern England by evening. That was good news: cloud provided a place to hide.

When they reached Norderney – a small island in the North Sea used as a navigation pinpoint – Peter spotted several other zeppelins. The sun shone brightly on their silver fabric. One of them, well to the rear, was easily recognized as the Dragon: her engines were worn out with so many war flights over these waters, so that her mechanics had to nurse the noisy machinery all the way. Nearer was the L23, with another naval airship moving through the mist beyond. It was a big raid today. Rumours said that there were a dozen naval airships engaged, and three or four army airships, too. Perhaps this would be the raid that would convince the British to seek peace terms. The newspapers all said that the British were reeling under the air raids on London, and the foolhardy British offensive along the river Somme in July had been a bloodletting for them.

For Peter, London was just a dim memory. It seemed a long time ago since he had last visited his grandparents in the big house there. He remembered his grandfather and the big English fruitcakes that were served at four o’clock each day. He remembered the busy streets in the City, where Grandfather had an office, and the quiet gardens and the street musicians to whom Grandfather always gave money. Especially vividly he recalled the piper, a Highlander in kilt and full Scots costume. He seemed too haughty to ask for money, but he stooped to pick up the coins thrown from the nursery window. The piper always came by about teatime, and the little German band came soon after. The bandleader was a big fellow with a red face and furious arm movements. He was astonished when Pauli responded to their music with rough and rude Berlin slang.

Peter’s memories of London had no meaning for him now. His boyhood desire to become an explorer was almost forgotten. The war had changed him. He’d lost too many comrades to relish these bombing missions. He was proud of his active, dangerous role, but when victory came he’d be content to spend the rest of his life in Berlin.

The whistle on the speaking tube sounded. Peter took the whistle from the tube, which he then put to his ear: ‘Hello?’ It was the lookout reporting the sighting of a ship: a German destroyer heading for Bremen. Peter noted it in the log and went back to his charts. They were at the rendezvous. Now commenced the worst part of the mission. Here at the rendezvous there would be hours of waiting, the engines ticking over just enough to hold position in the air. A skeleton crew on duty and anything up to a dozen men in hammocks slung along the gangways. No one would sleep; no one ever slept. You just stretched out and wondered what the night would bring. You remembered the stories about the airships that had broken up in mid-air or burst into flames. You wondered if the British had improved upon their anti-aircraft gunfire or perfected the incendiary bullets that the fighter planes fired.

The whitecapped sea would soon darken. But the days were long up here in the sky. Although the sun sank lower and lower, the waiting airships remained bathed in its light, glowing with that golden luminosity that is so like flame.

‘Winter. Leave whatever you’re doing and go to the number-two gun position: the telephone is not working.’

The observation officer was not a bad fellow, but he, too, succumbed to the nervousness of these waiting periods. Peter knew that there was nothing wrong with the telephone. The gunners were down inside the hull, out of the cold airstream, trying to keep warm. Once you got cold there was no way to get warm again: there was no such thing as a warm place on a naval airship. And who could blame the gun crew? There was no chance of enemy aircraft out here, so far from the English coast.

‘Ja, Herr Oberleutnant. Right away,’ Peter saluted him. Saluting was not insisted on in such circumstances, but Hildmann, like most regular officers of the old navy, didn’t like the ‘sloppy informality’ of the Airship Division.

Peter climbed the short ladder that connected the control gondola to the keel. To get to the upper gun position took Peter right through the airship’s hull. As he walked along the narrow gangway, he looked down through the gaps in the flapping outer cover and could see the ocean, almost three thousand feet below. The water was grey and spumy, speckled with the last low rays of sunlight coming through the broken cloud. Peter didn’t look down except when he had to. The ocean was a threatening sight. He had never enjoyed sailing since that day when he’d nearly drowned, and the prospect of serving on a surface vessel filled him with horror.

Some light was reflected from below, but the inside of the airship was dark. Above him the huge gas cells moved constantly. All around him there were noises: it was like being in the bowels of some huge monster. Besides the rustling of the gas cells there was the creaking of the aluminium framework along which he walked and the musical cries of thousands of steel bracing wires.

It was a fearsomely long vertical ladder that took him up between the gas cells to the very top of the envelope. Finally he emerged into the daylight on the top of the zeppelin. Suddenly it was very sunny, but the air was bitterly cold and he had to hold tight to the safety rail. What a curious place it was up here on the upper side of the hull. The silver fabric sloped away to each side, and the great length of the airship was emphasized. What an amazing achievement it was for man to build a flying machine as big as a cathedral.

Peter stood there staring for a moment or two. To the port-side he could see two other zeppelins. They were higher, by several hundred feet. Ahead was a flicker of light reflected off another airship’s fabric. That would be the old Dragon fighting to gain height. She’d caught up with the armada. It was good to see her so close; Peter had friends aboard her. They were not alone here in the upper air.

It was late afternoon. Still the airships glowed with sunlight. Soon, as the sun sank lower, the airships would darken one by one, darken like lights being extinguished. Then, when even the highest one went dark, they would move off towards England. Peter shivered; it was cold up here, very cold.

‘Hennig!’ called Peter loudly. He knew where the fellow would be hiding: all the gunners took shelter, but Hennig was the laziest.

‘What’s wrong, Herr Leutnant?’ He emerged blinking into the light and behind him came the loader, a diminutive youth named Stein, who followed the gunner everywhere. Stein was a Bolshevik agitator, though so far he’d been too sly to be caught spreading sedition amongst the seamen. Still, his cunning hadn’t saved him from several nasty beatings from fellow sailors who opposed his political views. Hennig was not thought to be a Bolshevik, but the two men were individualistic to the point of eccentricity, and neither would be welcomed into other gun teams. So they had formed an alliance, a pact of mutual assistance. Erich Hennig pushed his assistant gently aside. It was a gesture that said that if there was any blame to be taken he would take it. ‘What’s wrong, Leutnant?’ he said again. Hennig was a slim, pale youth of about Peter’s age. His dark eyes were heavy-lidded, his lips thin and bloodless.

‘You should be at the gun, Hennig.’

‘Ja, Herr Leutnant.’ Hennig smiled. It was a provocative and superior smile, the smile a man gave to show himself and others that he was not subject to authority. It was a smile for Peter Winter alone: the two men knew each other well. Winter had known Hennig since long before both men volunteered for the navy. Erich Hennig lived in Wedding; his father was a skilled cooper who worked in the docks mending damaged barrels. The apartment in which he grew up, with half a dozen brothers and sisters, was cramped and gloomy. At school Hennig proved below average at lessons, but he earned money by playing the piano in Bierwirtschaften – stand-up bars – and seedy clubs. It was a club owner who brought Erich Hennig’s talent to the attention of the amazing Frau Wisliceny. And through her efforts Hennig spent three years studying composition and theory at the conservatoire. By the time war broke out, Erich Hennig was being spoken of as a talent to watch. In April 1914 he’d given a series of recitals – mostly Chopin and Brahms – at a small concert hall near the Eden Hotel. There was even a paragraph about it in the newspaper: ‘promising,’ said the music critic.

Peter had met Hennig frequently at Frau Wisliceny’s house. Once they’d even played duets, but no friendship ever developed between them. Hennig was fiercely competitive. He saw the privileged Peter Winter as a spoiled dilettante who lacked the passionate love for music that Hennig knew. He’d actually heard Peter Winter discussing with the Wisliceny daughters whether he should pursue a career in music, study higher mathematics, or just prepare himself for a job alongside his father. This enraged Hennig. For Hennig it was a betrayal of talent. How could any talented musician – and even Erich Hennig admitted to himself, if not to others, that Peter Winter was no less talented than himself – speak of any other career?