По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

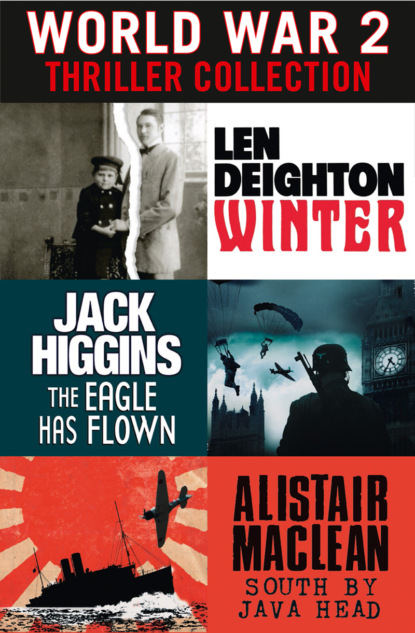

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘You know what young people are like, Foxy. He has this mad idea of becoming a musician. He doesn’t understand what a musician’s life is like.’

‘Is he talented?’

‘They tell me so, but talent is no guarantee that a man will earn a living. On the contrary, the more talent a man has the less likely he is to do well.’

‘Surely not?’

‘The scientists in my factory, the engineers who design the engines and the structures: what talents they have, and yet they will never get more than a simple living wage. Most of them could make far more money in the sales department, but they are too interested in their work to change. Talent is an impediment to them. Look at all the penniless artists desperate to sell their work, and the musicians who beg in the street.’

‘And so you’ve forbidden Peter to study music?’ asked Fischer provocatively.

Winter knew that Fischer was baiting him in his usual amiable way but he responded vibrantly. ‘If he wants to study music, that’s entirely up to him. But he can’t expect to enjoy himself playing music while others work to supply him with money.’

‘You’d cut him off without a penny?’ said Fischer with a smile. ‘That’s hard on the boy, Harry.’

‘If he wants to inherit the business, he must work. I have no patience with people like Frau Wisliceny, who gives the boy these crazy notions.’

‘Frau Wisliceny – Professor Wisliceny’s wife? But her “salon” is the most famous in Berlin. The world’s finest musicians take tea there.’

‘Yes, Frau Professor Doktor Wisliceny, I should have said…. And so do all sorts of other riffraff: psychologists, painters, novelists, poets and even socialists.’

Fischer decided not to reveal the fact that he had tea there regularly, too, and spent happy hours talking to the ‘riffraff’. ‘But if Frau Wisliceny thinks your son Peter has talent …What does he play?’

‘Piano. I won’t have one in the house, so he goes there to practise. My wife encourages him, I’m afraid. At first they thought that they’d force me to buy one for him but I wouldn’t yield. Professor Wisliceny must be a strange fellow to put up with it. How did he make his money?’

Fischer smiled. ‘Ah, that rather goes against your theory. The professor is a very clever chemist…synthetic dyestuffs.’

‘He made money from that?’

‘These aniline dyes save all the time, trouble and expense of getting dyes from plants, minerals, or animals. He makes a lot of money selling his expertise. You should bear him in mind, Harry, when you are making Peter toe the line.’

Winter was not amused. ‘I’m not talking about scientists. I don’t want a musician in the family.’

‘Too bohemian?’

‘I’m not fond of the Wislicenys. People like that should not encourage the troublemakers.’

‘They are good people, Harry.’ He wanted to calm Winter’s anger. ‘And the three Wisliceny girls are the prettiest in all Berlin. The youngest one, Lisl, would be a match for your youngest boy.’ Fischer couldn’t resist teasing Harry Winter. ‘She’s a gifted little girl: plays the piano at the conservatoire.’

‘A little more brandy?’ said Harry Winter.

The question was never answered, for at that moment they heard one of the maids screaming. She screamed twice and then came racing – falling almost – down the front stairs, the ones the servants were not permitted to use. ‘She’s dead. The mistress is dead!’

Harry Winter rushed to the door and stepped out of his study fast enough to catch the hysterical girl in his arms. ‘Stop it!’ he shouted so fiercely that for a moment she was silent. ‘Sit down and stop that stupid noise.’

‘She’s dead,’ said the girl, more quietly this time but with great insistence. She was shaking uncontrollably.

Winter ran up the stairs two at a time. He was no longer as fit as he’d once been and the exertion left him breathless as he raced into his wife’s room.

Veronica, fully dressed in a long green tea gown but with her golden hair disarranged, was sprawled across the bed. Winter rolled her over and then gently lifted an eyelid to see her eye.

‘My God!’ said Fischer, who’d followed him into the room. ‘It smells like a hospital in here. What’s wrong?’

‘She’s all right.’ Winter looked at his friend and hesitated before saying more. ‘It’s chloroform. My wife takes it in order to sleep.’

‘Shall I send for a doctor?’

‘No, I know what to do.’ Winter went to the door and said to the chambermaid, ‘Send Frau Winter’s personal maid to help her to bed. And tell Hauser that Frau Winter is unwell. He’s to keep the children and the servants from disturbing her.’

Fischer looked round the room. This was Veronica’s sanctum: floral wallpaper and bows and canopied bed. Harry’s bedroom – more severely ordered, with mahogany and brass – was next door.

‘It’s happened before?’ said Fischer as Winter closed the door on the maid and turned back to him.

‘Yes,’ said Winter. He went to the bed and looked at his wife. Why had she done this to him? Winter was too self-centred to see Veronica’s actions as anything but inconveniences.

Fischer looked at him with sympathy. So this was why Veronica was not much seen lately in Berlin society. Chloroform wasn’t taken to combat insomnia; it was a drug taken for excitement by foolish young people or by people who could no longer face the bleak reality of their world. Veronica was American, of course; all this talk of war must have put a strain on her. ‘How long has this been going on, Harry?’

There was no point in telling lies. ‘We went to Travemünde in the summer of 1910. Her brother, Glenn, was with us. It started about that time.’ He picked up the empty bottle and the gauze pad, sniffed at it, and grimaced. ‘I’m damned if I know where she gets the stuff.’

‘It’s easy enough to get, if you want it badly enough,’ said Fischer who knew about such things. ‘Any pharmacist stocks it and hospitals use it by the bucketful.’ He looked at Harry, who was now sitting on the bed embracing his unconscious wife. ‘Is everything all right between you?’ Fischer was one of the few men who could be so candid with him.

‘I love her. I love her very much.’ Winter fingered the things on his wife’s bedside table: a Bible, a German-English dictionary and some opened letters. Winter put the letters into his pocket. He wanted to see who was writing to his wife. Like most womanizers, he was eternally suspicious.

‘With respect, Harry, that’s not what I asked.’

‘There are no other men. Of that I’m sure.’

‘So what now?’ Fischer was embarrassed to find himself suddenly at the centre of this domestic tragedy. But Harald Winter and his wife were old friends.

‘I’ll have to send for the Wisliceny woman. She’s become Veronica’s closest friend. She looked after her when this happened before.’ He looked up at Fischer. ‘It’s not life and death, Foxy. She’ll come out of it.’

‘Perhaps she will, but it’s damned serious. You must talk to your wife, Harry. You must find out what’s troubling her. Maybe she should see one of these psychologist fellows.’

‘Certainly not!’ said Winter. ‘I won’t have some damned witch doctor asking her questions that don’t concern him. She must pull herself together.’ Winter hated to think of some such fellow – Austrian Jews, most of them were – prising from his wife things that were family matters. Or business secrets.

‘It’s not so easy, Harry. Veronica is sick.’

Winter still felt affronted by his wife’s behaviour. How could she make this scene while Fischer was their guest? ‘She has servants, money, children, a husband. What more can she want?’

Love, thought Fischer, but he didn’t say it. Was Harry still making those frequent trips to Vienna to see his Hungarian mistress? And how much did this distress Veronica? From what he knew of American women, they did not readily adapt to such situations. But Fischer did not say any of this either; he just nodded sympathetically.

Winter looked at his pocket watch. ‘It’s so late! What times she chooses for these antics. Little Paul has brought a friend home from his military school, and my elder son, Peter, will be arriving soon.’

But, however much Winter tried to put on a bold face, it was obvious to Fischer that Veronica’s overdosing had shaken him. Winter had even forgotten about his investment programme and Fischer’s contribution to it. You’re a damned hard man, thought Fischer, but he didn’t say it.

At that time, Peter was at Frau Wisliceny’s house off Kant Strasse. He’d spent two happy hours practising the piano under the critical but encouraging supervision of Frau Wisliceny. But now he was drinking coffee in the drawing room accompanied by the eldest of the three Wisliceny daughters. Her name was Inge. She was tall, with a full mouth that smiled easily, and dark hair that fell in ringlets around her pale oval face.

‘You will have to tell them, Peter,’ she said. ‘Your parents will be even more angry if you delay telling them.’