По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

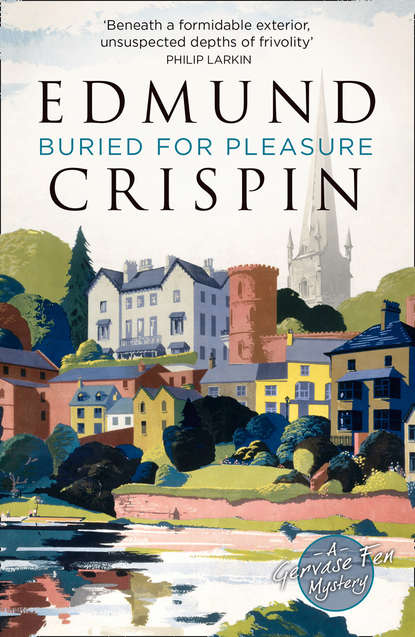

Buried for Pleasure

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘No, no,’ Fen assured him. ‘I never had any doubt about what you were doing. But I imagine few detective novelists can be as scrupulous.’

The man relaxed suddenly, and began wiping his forehead with a brightly coloured handkerchief. He picked up the reefer jacket and put it on.

‘One’s plots are necessarily improbable,’ he said a trifle didactically, ‘but I believe in making sure that they are not impossible.’ His utterance was prim and selfconscious, like himself. ‘Short of murder itself, I try everything out before finally adopting it for a book, and really, you would be surprised at the number of flaws and difficulties which are revealed in the process.’

Fen put his elbows on the top bar of the gate and leaned there comfortably.

‘And of course’, he said, ‘it must enable you to get to some extent inside the mind of the murderer.’

An expression of mild repugnance appeared on the man’s face. ‘No,’ he said, ‘no, it doesn’t do that.’ The subject seemed painful to him, and Fen felt that he had committed an indiscretion. ‘The fact is,’ the man went on, ‘that I have no interest in the minds of murderers, or for that matter,’ he added rather wildly, ‘in the minds of anyone else. Characterization seems to me a very over-rated element in fiction. I can never see why one should be obliged to have any of it at all, if one doesn’t want to. It limits the form so.’

Fen agreed, with no special conviction, that it did, and particularly in the case of detective stories. ‘I read a good many of them,’ he said, ‘and I must know yours. May I ask your name?’

‘Judd,’ the man replied, ‘my name is Judd. But I write’ – he hesitated, in some embarrassment – ‘I write under the pseudonym of “Annette de la Tour”.’

‘Ah, yes,’ said Fen. Annette de la Tour’s books, he remembered, were complicated, lurid, and splendidly melodramatic. And certainly they made no concessions to the Baal of characterization. He said: ‘Your work has given me a great deal of pleasure, Mr Judd.’

‘Has it?’ said Mr Judd eagerly. ‘Has it really? I’ve been writing for twenty years, and no one has ever said anything like that to me before. My dear fellow, I’m so grateful.’ His eyes sparkled with innocent pleasure. ‘And it’s all the better coming, as it evidently does, from an intelligent man.’

Upon this shameless quid pro quo he paused expectantly, and Fen, feeling that he was required to identify himself, did so. Mr Judd clapped his hands together with excitement.

‘But how splendid!’ he exclaimed. ‘Of course I’ve followed all your cases. We must have a very long talk together, a very long talk indeed. Are you staying here?’

‘Yes.’

‘For long?’

‘Until after polling day. I’m standing for Parliament.’

Mr Judd was taken aback.

‘Standing?’ he repeated dazedly. ‘For Parliament?’

‘It is my wish to serve the community,’ Fen said.

Confronted with this pronouncement, Mr Judd showed himself either more credulous or more courteous than Diana had been.

‘Very commendable,’ he murmured. ‘To tell you the truth, I had rather forgotten there was a by-election in progress… What interest do you represent?’

‘I’m an Independent.’

‘Then you shall have my vote,’ said Mr Judd, narrowly forestalling a primitive attempt at canvassing on Fen’s part. ‘And if I had fifty votes,’ he added lyrically, ‘you should have them all. Tell me, which of my books do you think the best?’

Fen rummaged in his mind, seeking not for that book of Mr Judd’s which he thought the best, but for the one which Mr Judd was likely to cherish most. ‘The Screaming Bone,’ he said at last.

‘Admirable!’ said Mr Judd, and Fen was pleased that his diagnosis had been correct. ‘I’m so glad you enjoyed that one, because the critics were very down on it, and yet I’ve always thought it the finest thing I’ve done. Mind you, the critics are down on all my books, because they haven’t any psychology in them, but they were particularly harsh about that one… You’re very perceptive, Professor Fen, very perceptive indeed.’ He beamed approval. ‘Still, we mustn’t waste time talking about my nonsense,’ he concluded insincerely. ‘Where are you heading for?’

‘I think’ – Fen glanced at his watch – ‘that it’s about time I was strolling back to the village.’

Mr Judd’s face fell. ‘What a pity – I have to go in the opposite direction, or we could have walked along together and talked,’ he said with great simplicity, ‘about my books. Still, you must come and have a meal with me – I live in a cottage only a quarter of a mile from here. What about lunch today?’

Fen said: ‘I’m afraid, you know, that I’m going to be very busy during the coming week,’ but Mr Judd’s disappointment was so manifest and poignant that he was moved to add: ‘But I dare say we can fit something in.’

‘Please try,’ said Mr Judd earnestly. ‘Please try. My telephone number is Sanford 13, and you needn’t hesitate to ring me at any time. Where are you staying?’

‘The Fish Inn,’ said Fen.

These words produced, unexpectedly enough, a marked change in Mr Judd. A new light appeared in his eyes – a light which Fen could not but associate with the more disreputable antics of satyrs in classic woods. In tones of reverence he said:

‘The Fish Inn… Tell me, have you come across that beautiful girl?’

‘The blonde?’

‘The blonde.’

‘Well, yes. She brought me my early morning tea.’

Mr Judd drew in his breath sharply.

‘She brought you your tea,’ he said, somehow investing Fen’s prosaic statement with the glamour of a phallic rite. ‘And was she wearing that powder-blue frock?’

‘I can’t really remember,’ said Fen vaguely. ‘It was something tight-fitting, I think.’

‘Tight-fitting,’ Mr Judd repeated with awe. He looked at Fen as he might have looked at a man who had lit a fire with bank-notes. ‘Do you know, I think she’s the most beautiful girl I’ve ever seen… Do you think she reads my books? I’ve never dared ask her.’

‘I doubt if she’s intelligent enough to read anyone’s books.’

Mr Judd sighed. ‘It’s just as well, perhaps,’ he said, ‘because she mightn’t like them…’ He veered from the topic with obvious reluctance. ‘Well, well, I mustn’t keep you.’

‘Don’t forget your revolver,’ said Fen.

‘No, I’d better not do that. Apart from anything else, I haven’t got a licence for it.’

‘And by the way – what is the point of throwing it into the pond and pulling it out again?’

‘That,’ Mr Judd explained, ‘is because the murderer wants to give the impression that he left it there at the time of the murder, and only retrieved it a good deal later, for fear of its discovery. The detective, of course, finds it somewhere quite different.’

‘But why should the murderer want to give that impression?’

Mr Judd became evasive. ‘I think you’d better read the book when it comes out. I’ll send you a copy… You realize about the coat, of course. It belongs to the victim, and the murderer wears it inside out so that when he carries the body the coat gets bloodstains on it where they ought to be, on the inside.’

‘Yes,’ said Fen. ‘Yes, I’d grasped that.’

‘Very quick of you. Well, you’ll let me know when you can pay me a visit, won’t you? I shall look forward to it, look forward to it enormously. I live a very solitary life, because there’s no one intelligent to talk to in Sanford Angelorum except the Rector, and his interests are confined to theology and birds and gardening, about all of which his information is tiresomely complete. Yes, you must certainly come and have a meal, and I shall be interested to hear any criticisms you may have to make about my books… Yes. Well, goodbye for the present.’

‘Goodbye,’ said Fen, shaking him by the hand. ‘I’ve very much enjoyed meeting you, and I hope I didn’t interrupt your test.’

‘Not in the least,’ Mr Judd assured him. ‘All I had left to do was to take the body into the village and put it on top of the War Memorial… Well, then, I shall hope to be seeing you.’