По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

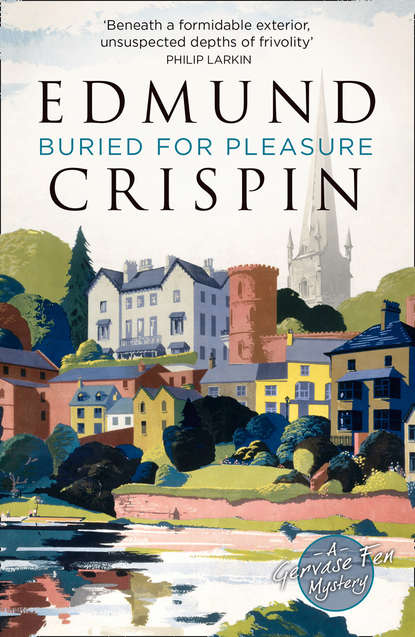

Buried for Pleasure

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter Five (#ue8bc9131-63ab-5413-9328-0a1aae04bdcc)

They parted cordially, Mr Judd to retrieve his revolver and Fen to return to the village, full of regret at having missed seeing Mr Judd hoisting an imaginary corpse on to the War Memorial, and speculating on Mr Judd’s murderer’s motives in performing this laborious and public act.

He had reached the point provisionally identified as Sweeting’s Farm, and had worked out a rambling, intricate theory about Mr Judd’s murderer which involved the propinquity of an expatriate tulip-grower from Harlingen, when he saw approaching him, at a slow and thoughtful pace, the self-styled Crawley, who was now wearing a tweed cap and a tweed knickerbocker suit and carrying a fishing-rod in a manner which suggested that he was unused to it.

The conviction of having seen or known this man in some other context returned to Fen with redoubled force. He decided to accost him and, if possible, resolve the problem.

In this project, however, he was over-sanguine. The man looked up, observed his purposeful approach, glanced hurriedly about him, and in another moment had bounded over a stile and was hastening precipitately away across the field to which it gave access.

Shaken at being thus obviously avoided, Fen halted; then resumed his walk in a less cheerful mood. At one time and another he had made contact with various persons whom the law regarded with disfavour, and it was not impossible that ‘Crawley’ was one of them. In that case Fen had a responsibility for preventing whatever mischief might be contemplated – only the trouble was that he could not be sure that any mischief was contemplated…

He inspected the miscellaneous lumber-room of his mind in the hope of enlightenment, but vainly. He was still inspecting it, still vainly, when he arrived back at the inn.

His walk had taken him longer than he imagined, and it was already ten past eleven. The bar, however, got little custom before midday, and it was empty except for Myra, for the blonde, and for a sullen-looking Cold-Comfort-Farmish sort of man who was looming across at Myra and speaking slowly but with great vehemence.

‘I’ll ’ave ’ee,’ he was saying, ‘I’ll get ’ee, see if I doan’t.’

He pointed a dramatic finger at Myra who, nevertheless, did not seem much perturbed. ‘Don’t be so ruddy daft, Sam,’ she said.

‘I doan’t mind you’m being a barmaid,’ the Cold-Comfort-Farmish man resumed graciously. ‘I’m not one o’ your proud ’uns. Come on, Myra, be a sport. ’Twoan’t take not five minutes.’

Myra, unmoved by this promise of despatch, indicated Fen.

‘You’re making a fool of yourself in front of the gentleman, Sam,’ she said. ‘Finish your drink like a good boy and go back to the farm. I know you didn’t ought to be here, and you’ll cop it if Farmer Bligh finds out.’

The passionate rustic turned upon Fen a look of intense hatred, emptied his glass, wiped his mouth, muttered something derogatory to womanhood and strode out of the bar. In a moment he reappeared outside the window, which was slightly grimy, traced on it with his forefinger the words I LOVE YOU in reverse, so that they could be read from inside, glowered at them all, and went away.

‘That’s clever,’ said Myra, in reference apparently to the calligraphic feat. ‘He must have been practising it at home.’

‘Ah,’ said Fen non-committally.

‘Of course, Sam, he’s a chronic case – been carrying on like that for nearly two years now. It’s flattering in a way, but I can’t think how he doesn’t get sick of it.’

‘I suppose,’ said Fen, with hazy recollections of novels about bucolic communities, ‘that time doesn’t mean very much to him.’

‘What would you like to drink, my dear?’

‘A pint of bitter, please. And you?’

‘Oh, thank you, sir. I’ll have a Worthington, if I may.’

Fen settled on a stool by the bar, and while they drank talked to Myra about the people he had met in Sanford Angelorum.

Of Diana he learned that she was an orphan – the daughter of a former local G.P. who had died almost penniless through never sending in bills – that she was much liked by the local people, and that she was reputed to be in love with young Lord Sanford.

Of young Lord Sanford he learned that he was in his last year at Oxford, that he was a zealous Socialist, that he lived not in Sanford Hall itself but in the dower-house attached to it, that the local people would have liked him better if he had not been so conscientiously democratic, and that he might or might not be going to marry Diana.

Of Sanford Hall, he learned that young Lord Sanford had presented it to the nation, and that the nation had promptly turned it into a mental asylum run by the Home Office.

Of Mr Judd, he learned that he kept himself to himself.

Of Myra, he learned that her husband had died five years previously, and that she liked working in pubs.

Of Mr Beaver, he learned that he was a man of great initial determination but little staying-power.

Of Jane Persimmons, he learned that she was very quiet and reserved, that she had not disclosed her business in the village, that Myra liked her, and that she was fairly certainly not well off.

‘Then she’s a stranger in the district?’ Fen asked.

‘Yes, my dear. And the man is, too – Crawley, I mean. Have you seen him yet?’

Fen said that he had.

‘He’s a queer one,’ Myra went on. ‘Come here three days ago. Off on his own all day and every day – sometimes doesn’t even have breakfast. Says he goes fishing, but no one ever comes here to fish: there’s nothing in the Spoor but two or three minnows. And anyway, it’s obvious he knows no more about fishing than my backside. He’s a mystery, he is. Jacqueline mistrusted him from the start – didn’t you, Jackie?’ she said to the blonde barmaid.

Jacqueline, who was patiently polishing glasses, nodded and favoured them with a radiant smile. Fen noted, for Mr Judd’s future information, that she was wearing a plain black frock with white at the wrists and neck, and a rather beautiful old marcasite brooch.

Myra was regarding her with considerable fondness.

‘Isn’t she lovely?’ said Myra with proprietary pride. ‘Talk about dumb ruddy blondes.’

The dumb ruddy blonde, unembarrassed, glowed at them again, like a large electric bulb raised gently to its fullest power and then as gently dimmed.

‘And she’s everything you imagine blondes with figures aren’t,’ said Myra. ‘Goes to church regular, looks after her pa and ma in Sanford Morvel, doesn’t smoke or drink, and hardly ever goes out with men. But, of course, the only thing people want to do is just look at her – almost the only thing, that is,’ Myra corrected herself in the interests of accuracy.

Jacqueline smiled exquisitely a third time, and continued peaceably to polish glasses. A customer came in, and Myra abandoned Fen in order to attend to him. At the time of Fen’s return to the inn, all had been quiet. But now a light tapping from some other quarter of the building indicated that Mr Beaver’s interregnum, whatever might have been its cause, was over. The tapping grew rapidly in vehemence, and was soon joined, fugally, by other similar noises.

‘My God,’ said Myra. ‘They’re off again.’

Fen thought the moment appropriate to demand an explanation of the repairs.

‘It’s quite simple, my dear,’ said Myra. ‘In the normal way we only get the locals in here, and, of course, that means the pub doesn’t make much money. So Mr Beaver decided he’d like to turn it into a sort of roadhouse place, swanky-like, you know, and expensive, and get people to come here in their cars from all over the county.’

‘But that’s a deplorable ambition,’ Fen protested.

‘Well, you can understand it, can’t you?’ said Myra tolerantly. ‘I know there’s some as say the village ought to stay unspoiled, and all that, but it’s my opinion that if people aren’t allowed to make as much money as they can we shall all be worse off.’

Fen considered this fiscal theory and decided that, subject to a good deal of qualification, there was something in it.

‘But still,’ he said, ‘it does seem a pity. You know the sort of customers you’ll get; loud-voiced, red-faced men with Hudson Terraplanes and toothbrush moustaches, and little slinky girls with geranium lips and an eye to the main chance, smoking cigarettes in holders.’

Myra sighed a little at this vision of the coming Gomorrah, but – since unlike Fen she was not prone to aesthetic bigotry – did not seem, he thought, to be seriously dismayed.

‘Anyway,’ she said, ‘it’s their pub to do what they like with. They tried to get a licence for the renovations, but the Ministry refused it. So they’re doing the whole thing themselves.’

‘Doing it themselves?’

‘There’s a regulation, you see, that if you don’t employ workmen, and don’t spend more than a hundred pounds, you can do up your house, or whatever it is, yourself. Mr Beaver’s got his whole family at it, and some of his friends drop in now and again to lend a hand.’