По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

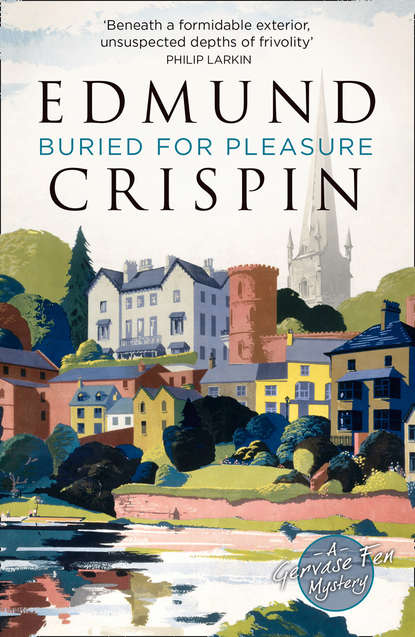

Buried for Pleasure

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The inn proved to be more prepossessing inside than out. There was only one bar – the tiresome distinction of ‘lounge’ and ‘public’ having been so far excluded – but it was roomy and spacious, extending half the length and almost all the width of the house. The oak panelling, transferred evidently from some much older building, was carved in the linenfold pattern; faded but still cheerful chintz curtains covered the windows; a heavy beam traversed the ceiling; oak chairs and settles had their discomfort partially mitigated by flat cushions. The decoration consisted largely of indifferent nineteenth-century hunting prints, representing stuffed-looking gentlemen on the backs of fantastically long and emaciated horses; but in addition to these there was, over the fireplace, a canvas so large as to constitute something of a pièce de résistance.

It was a seascape, which showed, in the foreground, a narrow strip of shore, up which some men in oilskins were hauling what looked like a primitive lifeboat. To the left was a harbour with a mole, behind which an angry sky suggested the approach of a tornado. And the rest of the available space, which was considerable, was taken up with a stormy sea, flecked with white horses, upon which a number of sailing-ships were proceeding in various directions.

This spirited depiction, Fen was to learn, provided an inexhaustible topic of argument among the habitués of the inn. From the seaman’s point of view, no such scene had ever existed, or could ever exist, on God’s earth. But this possibility did not seem to have occurred to anyone at Sanford Angelorum. It was the faith of the inhabitants that if the artist had painted it thus, it must have been thus. And tortuous and implausible modes of navigation had consequently to be postulated in order to explain what was going on. These, it is true, were generally couched in terms which by speakers and auditors alike were only imperfectly understood; but the average Englishman will no more admit ignorance of seafaring matters than he will admit ignorance of women.

‘No, no; I tell ’ee, that schooner, ’er’s luffin’ on the lee shore.’

‘What about the brig, then? What about the brig?’

‘That’s no brig, Fred, ’er’s a ketch.’

‘’Er wouldn’t be fully rigged, not if ’er was luffing.’

‘Look ’ere, take that direction as north, see, and that means the wind’s nor’-nor’-east.’

‘Then ’ow the ’ell d’you account for that wave breaking over the mole?’

‘That’s a current.’

‘Current, ’e says. Don’t be bloody daft, Bert, ’ow can a wave be a current?’

‘Current. That’s a good one.’

At the moment when Fen first set eyes on this object, however, it had temporarily lost its hold on the interest of the inn’s clients. This was due to the presence of an elderly lady in a ginger wig who, surrounded by a circle of listeners, was sitting in a collapsed posture on a chair, engaged, between sips of brandy, in vehement and imprecise narration.

‘Frightened?’ she was saying. ‘Nearly fell dead in me tracks, I did. There ’e were, all white and nekked, lurking be’ind that clump of gorse by Sweeting’s Farm. And jist as I passes by, out ’e jumps at me and “Boo!” ’e says, “Boo!”’

At this, an oafish youth giggled feebly.

‘And what ’appened then?’ someone demanded.

‘I struck at ’im,’ the elderly lady replied, striking illustratively at the air, ‘with me brolly.’

‘Did you ’it ’im?’

‘No,’ she admitted with evident reluctance. ‘’E slipped away from me reach, and off ’e went before you could say “knife”. And ’ow I staggered ’ere I shall never know, not to me dying day. Yes, thank you, Mrs ’Erbert, I’ll ’ave another, if you please.’

‘’E must ’a’ bin a exhibitor,’ someone volunteered. ‘People as goes about showing thesselves in the altogether is called exhibitors.’

But this information, savouring as it did of intellectual snobbery, failed to provoke much interest. A middle-aged, bovine, nervous-looking man in the uniform of a police constable, who was standing by with a note-book in his hand, said:

‘Well, us all knows what ’tis, I s’pose. ’Tis one o’ they loonies escaped from up at ’all.’

‘These ten years,’ said a gloomy-looking old man, ‘I’ve known that’d ’appen. ’Aven’t I said it, time and time again?’

The disgusted silence with which this rhetorical question was received indicated forcibly that he had; with just such repugnance must Cassandra have been regarded at the fall of Troy, for there is something distinctly irritating about a person with an obsession who turns out in the face of all reason to have been right.

The adept in psychological terminology said: ‘Us ought to organize a search-party, that’s what us ought to do. ’E’m likely dangerous.’

But the constable shook his head. ‘Dr Boysenberry’ll be seeing to that, I reckon. I’ll telephone ’im now, though I’ve no doubt ’e knows all about it already.’ He cleared his throat and spoke more loudly. ‘There is no cause for alarm,’ he announced. ‘No cause for alarm at all.’

The inn’s clients, who had shown not the smallest evidence of such an emotion, received this statement apathetically, with the single exception of the elderly lady in the wig, who by now was slightly contumelious from brandy.

‘Tcha!’ she exclaimed. ‘That’s just like ’ee, Will Sly. An ostrich, that’s what you are, with your ’ead buried in sand. “No cause for alarm,” indeed! If it’d bin you ’e’d jumped out at, you’d not go about saying there was “no cause for alarm”. There ’e were, white and nekked like an evil sperrit…’

Her audience, however, was clearly not anxious for a repetition of the history; it began to disperse, resuming abandoned glasses and tankards. The gloomy-looking old man buttonholed people with complacent iterations of his own foresight. The psychologist embarked on a detailed and scabrous account, in low tones, and to an exclusively male circle, of the habits of exhibitors. And Constable Sly, on the point of commandeering the inn’s telephone, caught the eye of the girl from the taxi for the first time since she and Fen had entered the bar.

‘’Ullo, Miss Diana,’ he said, grinning awkwardly. ‘You’ve ’eard what’s ’appened, I s’pose?’

‘I have, Will,’ said Diana, ‘and I think I may be able to help you a bit.’ She related their encounter with the lunatic.

‘Ah,’ said Sly. ‘That may be very useful, Miss Diana. ’E were making for Sanford Condover, you say?’

‘As far as I could tell, yes.’

‘I will inform Dr Boysenberry of that fact,’ said Sly laboriously. He turned to the woman who was serving behind the bar. ‘All right for I to use phone, Myra?’

‘You can use the phone, my dear,’ Myra Herbert said, ‘if you put tuppence in the box.’ She was a vivacious and attractive Cockney woman in the middle thirties, with black hair, a shrewd but slightly sensual mouth, and green eyes, unusually but beautifully shaped.

‘Official call,’ Sly explained with hauteur.

Myra registered disgust. ‘You and your official ruddy calls,’ she said. ‘My God!’

Sly ignored this and turned away; at which the lunatic’s first victim, becoming suddenly aware of his impending departure, roused herself from an access of lethargy to say:

‘And what about me, Will Sly?’

Sly grew harassed. ‘Well, Mrs ’Ennessy, what about you?’

‘You’re not going to leave me to walk ’ome by meself, I should ’ope.’

‘I’ve already explained to you, Mrs ’Ennessy,’ said Sly with painful dignity, ‘that there is no cause for alarm.’

Mrs Hennessy emitted a shriek of stage laughter.

‘Listen to ’im,’ she adjured Fen, who was contemplating his potential constituents with a hypnotized air: ‘Listen to Mr Knowall Sly!’ Her manner changed abruptly to one of menace. ‘For all you knows, Will Sly, I might be murdered on me own doorstep, and then where’d you be? Eh? Tell me that. And what’s me ’usband pay ’is rates for, that’s what I asks. I got a right to pertection, ’aven’t I? I got—’

‘Now, look ’ere, Mrs ’Ennessy, I’ve me duty to do.’

‘Duty!’ Mrs Hennessy repeated with scorn. ‘’E says’ – and here she again addressed Fen, this time with the air of one imparting a valuable confidence – ‘’e says ’e’s got ’is duty to do … Fat lot of duty you do, Will Sly. What about the time Alf Braddock’s apples was stolen? Eh? What about that? Duty!’

‘Yes, duty,’ said Sly, much aggrieved at this unsportsmanlike allusion. ‘And what’s more, the next time I catch you trying to buy Guinness ’ere out of hours—’

Diana interrupted these indiscretions.

‘It’s all right, Will,’ she said. ‘I’ll take Mrs Hennessy home. It’s not far out of my way.’

The offer restored peace and a semblance of amity. Sly went to the telephone. Fen paid Diana and retrieved his luggage from the taxi. Myra called time. The company grudgingly finished its drinks and departed, Diana enduring with angelic patience a new and more highly-coloured account of Mrs Hennessy’s adventure.