По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

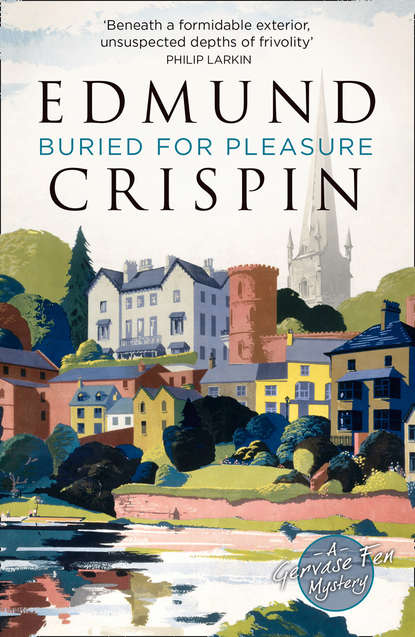

Buried for Pleasure

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

After a pause she went on:

‘You’re rather late starting your election campaign, you know. There’s only a week to go, and I haven’t seen a single leaflet about you, or a poster, or anything.’

‘My agent,’ said Fen, ‘is dealing with all that.’

The girl considered this reply in silence.

‘Look here,’ she said, ‘you’re a Professor at Oxford, aren’t you?’

‘Of English.’

‘Well, what on earth … I mean, why are you standing for Parliament? What put the idea into your head?’

Even to himself Fen’s actions were sometimes unaccountable, and he could think of no very convincing reply.

‘It is my wish,’ he said sanctimoniously, ‘to serve the community.’

The girl eyed him dubiously.

‘Or at least,’ he amended, ‘that is one of my motives. Besides, I felt I was getting far too restricted in my interests. Have you ever produced a definitive edition of Langland?’

‘Of course not,’ she said crossly.

‘I have. I’ve just finished producing one. It has queer psychological effects. You begin to wonder if you’re mad. And the only remedy for that is a complete change of occupation.’

‘What it amounts to is that you haven’t any serious interest in politics at all,’ the girl said with unexpected severity.

‘Well, no, I wouldn’t say that,’ Fen answered defensively. ‘My idea, after I’ve been elected—’

But she shook her head. ‘You won’t be elected, you know.’

‘Why not?’

‘This is a safe Conservative seat. You won’t get a look in.’

‘We shall see.’

‘You may confuse the issue a little, but you can’t affect it ultimately.’

‘We shall see.’

‘In fact, you’ll be lucky if you don’t lose your deposit. What exactly is your platform?’

Fen’s confidence waned slightly. ‘Oh, prosperity,’ he said vaguely, ‘and exports and freedom and that kind of thing. Will you vote for me?’

‘I haven’t got a vote – too young. And anyway, I’m canvassing for the Conservatives.’

‘Oh, dear,’ said Fen.

They fell silent. Trees and coppices loomed momentarily out of the darkness and were swept away again as though by a giant hand. The headlights gleamed on small flowers sleeping beneath the hedges, and the air of that incomparable summer washed in a warm tide through the open windows. Rabbits, their white scuts bobbing feverishly, fled away to shelter in deep, consoling burrows. And now the lane sloped gently downwards; ahead of them they could glimpse, for the first time, the scattered lights of the village…

With one savage thrust the girl drove the foot-brake down against the boards. The car slewed, flinging them forward, then skidded, and at last came safely to a halt. And in the glare of its headlights a human form appeared.

They blinked at it, unable to believe their eyes. It blinked back at them, to all appearance hardly less perturbed than they. Then it waved its arms, uttered a bizarre piping sound, and rushed to the hedge, where it forced its way painfully through a small gap and in another moment, bleeding from a profusion of scratches, was lost from view.

Fen stared after it. ‘Am I dreaming?’ he demanded.

‘No, of course not. I saw it, too.’

‘A man – quite a large, young man?’

‘Yes.’

‘In pince-nez?’

‘Yes.’

‘And with no clothes on at all?’

‘Yes.’

‘It seems a little odd,’ said Fen with restraint.

But the girl had been pondering, and now her initial perplexity gave way to comprehension. ‘I know what it was,’ she said. ‘It was an escaped lunatic.’

This explanation struck Fen as conventional, and he said as much.

‘No, no,’ she went on, ‘the point is that there actually is a lunatic asylum near here, at Sanford Hall.’

‘On the other hand, it might have been someone who’d been bathing and had his clothes stolen.’

‘There’s nowhere you can bathe on this side of the village. Besides, I could see that his hair wasn’t wet. And didn’t he look mad to you?’

‘Yes,’ said Fen without hesitation, ‘he did. I suppose,’ he added unenthusiastically, ‘that I ought really to get out and chase after him.’

‘He’ll be miles away by now. No, we’ll tell Sly – that’s our constable – when we get to the village, and that’s about all we can do.’

So they drove on, preoccupied, into Sanford Angelorum, and presently came to ‘The Fish Inn’.

Chapter Two (#ue8bc9131-63ab-5413-9328-0a1aae04bdcc)

Architecturally, ‘The Fish Inn’ did not seem particularly enterprising.

It was a fairly large cube of grey stone, pierced symmetrically by narrow, mean-looking doors and windows, and surrounded by mysterious, indistinguishable heaps of what might be building materials. Its signboard, visible now in the light which filtered from the curtained windows of the bar, depicted murky subaqueous depths set about with sinuous water-weed; against this background a silvery, generalized marine creature, sideways on, was staring impassively at something off the edge of the board.

From within the building, as Fen’s taxi drew up at the door, there issued noises suggestive of agitation, and periodically dominated by a vibrant feminine voice.

‘It sounds to me as if they’ve heard about the lunatic,’ said the girl. ‘I’ll come in with you, in case Sly’s there.’