По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

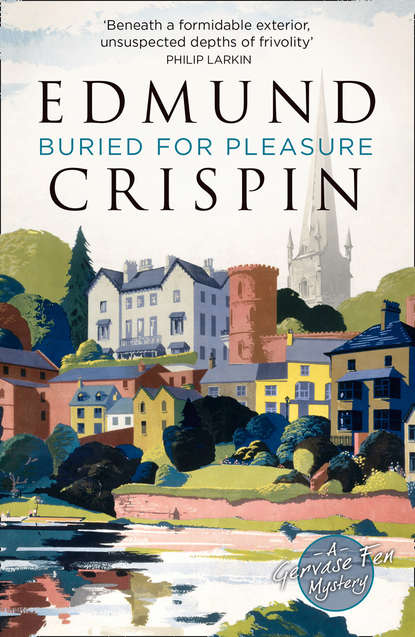

Buried for Pleasure

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Fen introduced himself to Myra, signed a register, and was shown to his room, which was comfortable and scrupulously clean. He ordered, obtained, and consumed beer, coffee, and sandwiches.

‘And I should like,’ he told Myra, ‘to be allowed to sleep on till ten tomorrow morning.’

At this, to his mystification, Myra laughed very happily, and, controlling herself at length, said: ‘Very well, my dear: good night,’ and tripped gracefully from the room, leaving him theorizing gloomily about what her unexpected reaction might mean.

There remained, for that evening, only one further incident which interested him. His visit to the bathroom gave him a glimpse of someone who was vaguely familiar – a thin, auburn-haired man of about his own age whom he saw vanishing in a dressing-gown into one of the other bedrooms. But the association which was so certainly in his mind refused to reveal itself, and though he pondered the problem while getting into bed, he soon abandoned it for lack of inspiration, and by the time the church clock struck midnight was sound asleep.

Chapter Three (#ue8bc9131-63ab-5413-9328-0a1aae04bdcc)

He was horribly awakened, in what seemed about ten minutes, by an outbreak of intensive hammering somewhere in the regions below.

He groped for his watch, focused his eyes with difficulty on its dial, and perceived that the time was only seven. Outside the bedroom windows the sun was shining brilliantly. Fen eyed it with displeasure. He was temperamentally a late riser, and the panache of virgin daylight made little appeal to him.

Meanwhile, the noise below was increasing in volume and variety, as if fresh recruits were arriving momently. And now it became clear to Fen’s fuddled mind that in this lay probably the reason both for Diana’s gnomic warning and for Myra’s irrepressible hilarity of the previous evening, when he had said he wished to sleep late. He uttered a groan of dismay.

It acted like a signal.

There came a tap on his door, and in response to his croak of invitation a girl entered so superlatively beautiful that Fen began to wonder if he were dreaming.

The girl was a natural platinum blonde. Her features were flawless. She had a figure like the quintessence of all pin-up girls. And she moved with an unselfconscious and quite unprovocative placidity, which made it evident that – incredible though it might seem – she was quite unaware of her perfections.

With a radiant smile she deposited a tray of tea on the bedside table; left the room, returned presently with his shoes, beautifully polished; smiled at him again; and the next moment, like a fairytale vision – though he could imagine no princess of the Perilous Realm capable of offering her lover such nuptial joys as this – was gone.

Dazed, Fen lit his early-morning cigarette; and the familiar unpleasantness of smoking it restored him to something like normality. He sipped tea and brooded over the hammering, which continued unabated. Soon it was interrupted by a noise which sounded like a very large scaffolding giving way.

Fen got up hurriedly, washed, shaved, dressed, and went downstairs.

The whole household was astir – as unless heavily drugged it could hardly fail to be. Fen found Myra Herbert out in the yard, contemplating a small, greyish, unalluring pig which seemed to be trying to make up its mind how to employ the day.

‘Good morning, my dear,’ Myra greeted him brightly. ‘Sleep well?’

‘Up to a point,’ said Fen with reserve.

She indicated the pig. ‘Did you ever see anything like him?’ she asked.

‘Well, no, now you mention it I don’t think I have.’

‘I’ve been cheated,’ said Myra, and the pig grunted, apparently in assent. ‘I like a young pig to be nice and pink, you know, and cheerful-like. But him – my God. I feed him and feed him, but he never grows.’

They meditated jointly on this phenomenon. A passing farm-labourer joined them.

‘’E don’t get no bigger, do ’e?’ he observed.

‘What’s the matter with him, Alf?’

The farm-labourer pondered. ‘’E’m a non-doer,’ he diagnosed at last.

‘A what?’

‘Non-doer. You’re wasting your time trying to fatten ’im. ’E’ll never get no larger. Better sell ’im.’

‘Non-doer,’ said Myra with disgust. ‘That’s a nice cheerful ruddy thought to start the day with.’

The farm-labourer departed.

‘I’ll say this for him, though,’ said Myra, referring to the pig, ‘he’s very affectionate, which is a point in his favour, I suppose.’

They turned back to the inn. Myra suggested that Fen might now like to have breakfast, and Fen agreed.

‘But what is happening?’ he demanded, indicating the hammering.

‘Renovations, my dear. They’re renovating the interior.’

‘But workmen never get started as early as this.’

‘Oh, it isn’t workmen,’ said Myra obscurely. ‘That’s to say…’

They came to a door in a part of the ground floor with which Fen was not yet acquainted, and from behind which most of the din seemed to be proceeding. ‘Look,’ said Myra.

The opening of the door disclosed a dense cloud of plaster dust in which figures could dimly be discerned engaged, to all appearance, in a labour of unqualified destruction. One of these – a man – loomed up at them suddenly, looking like a whitewash victim in a slapstick comedy.

‘’Morning, Myra,’ he said with disarming heartiness. ‘Everything all right?’

‘Oh, quite, sir.’ Myra was distinctly bland and respectful. ‘This gentleman’s staying here, and he wondered what was going on.’

‘Morning to you, sir,’ said the man. ‘Hope we didn’t get you up too early.’

‘Not a bit,’ Fen replied without cordiality.

‘I feel better already’ – the man spoke, however, more with determination than with conviction – ‘for getting up at six every morning … It’s one of the highroads to health, as I’ve always said.’

He fell into a violent fit of coughing; his face became red, and then blue. Fen banged him prophylactically between the shoulder-blades.

‘Well, back to the grindstone,’ he said when he had recovered a little. ‘I’ll tell you this much, sir, there’s a good deal to be said, when you want a thing done, for doing it yourself.’ Someone caught him a glancing blow on the arm with a small pick. ‘Careful, damn you, that hurt…’

He left them in order to expostulate in more detail. They closed the door and continued on their way.

‘Who was that?’ Fen asked.

‘Mr Beaver, who owns the pub. I only manage it for him. He’s a wholesale draper, really.’

‘I see,’ said Fen, who saw nothing.

‘Have your breakfast now, my dear,’ Myra soothed him, ‘and I’ll explain later.’

She conducted him to a small room where there was a table laid for three. Here, to his elation, she provided him with bacon, eggs, and coffee.

He had finished these, and come to the marmalade stage, when the door opened and he was surprised to see the fair-haired girl who had been his sole fellow-passenger on the train.