По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

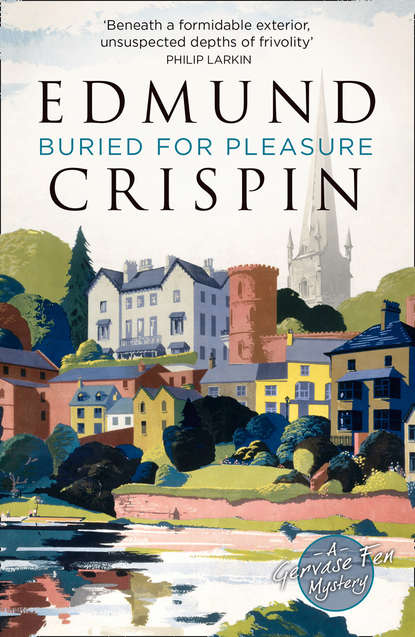

Buried for Pleasure

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Surely, though, it’s a job for an expert.’

‘Ah,’ said Myra sombrely. ‘You’re right there, my dear. But that’s Mr Beaver all over. Once he gets an idea into his head, nothing’ll stop him. And if you ask me—’

But what more she would have said Fen never learned. Even as she spoke, he had been conscious that a large and noisy car was pulling up at the door of the inn.

And now, with the consciously grandiose air of a god from a machine, a newcomer strode into the bar.

Chapter Six (#ulink_94f47f87-3ebc-56e0-b220-7befbb22e645)

The newcomer was a man of between thirty and forty, though a certain severity of expression made him seem rather older. He was tall and stringy, with a weather-beaten complexion, a long straight nose, bright, bird-like eyes, and thin brown hair which glistened with bay-rum; and he wore jodhpurs, riding-boots, a violent check hacking coat, and a yellow tie with horses’ heads on it. In his hand he carried a green pork-pie hat with ventilation holes in the top, so that it looked as if someone had been shooting at him.

He stalked to the bar, rapped on it, and demanded peremptorily to be told if Professor Fen were available.

‘I am Fen,’ said Fen.

The newcomer’s manner changed at once to one of great affability. He took Fen’s hand and joggled it up and down prolongedly.

‘My dear sir,’ he said, ‘this is a very great pleasure. Damme yes. Delighted, and all that… What are you having?’

‘Bitter, I think.’

‘A pint of bitter, Miss, and a large Scotch for me.’

‘You are Captain Watkyn?’ Fen asked mistrustfully.

‘You’ve got it in one, old boy,’ said Captain Watkyn with enthusiasm; it was as though he were commending Fen for the solution of a particularly awkward riddle. ‘The old firm in person, at your service now as always… Well, bungho.’

They drank.

‘It’s a good thing you’re a drinking man,’ Captain Watkyn added pensively. ‘I had to act for a T.T. once – Melton Mowbray, I think it was – and between ourselves, I had a pretty sticky time of it.’

‘Did he get in?’

‘No,’ said Captain Watkyn with satisfaction, ‘he didn’t. Mind you,’ he went on hurriedly, perceiving in this anecdote an element which might be interpreted to his own disadvantage – ‘mind you, he wouldn’t have got in even if the King – God bless His Majesty – had been sponsoring him… I tell you what, we’ll go and sit over by the window, where there’s some air.’

Carrying their drinks, they moved to the embrasure he had indicated and settled down there, Captain Watkyn with the relieved sigh of one who, after long and tedious journeyings, has returned home.

‘Snug little place,’ he observed, looking about him. ‘Might be a bit quieter, though, mightn’t it?’

Fen agreed that it might.

‘Well, never mind,’ said Captain Watkyn consolatorily, as though it had been Fen who had complained. ‘You might be very much worse off, if I know anything about it… Well, now, sir, you must let me have your instructions.’

‘What,’ Fen asked, ‘has been happening so far?’

‘A great deal,’ Captain Watkyn replied promptly. ‘A great deal has been happening. In the first place, I’ve induced ten people to nominate you – they’re a job lot, but they’re ratepayers, which is the only thing that matters. So that’s settled. And then, the posters and leaflets have arrived this morning from the printer. He’s taken a devil of a time doing them, but that’s all to the good.’

‘How is it all to the good? I don’t see—’

‘The point is, old boy,’ Captain Watkyn interrupted, ‘that you get quite an advantage by starting your campaign late. You acquire the charm of novelty. Start too early, and you’ll find people get sick of seeing your silly face peering at them from the hoardings (no offence meant). Now, you’re going to come down on them,’ he said, waxing suddenly picturesque, ‘like the Assyrian on whatever it was. They’ll be bowled over. They won’t have a chance to look about. Then along comes Polling Day, and you’re in.’

‘Yes,’ said Fen dubiously. ‘I dare say that’s so.’

‘You may depend on it, old boy. The old firm knows what it’s doing, believe you me. Now then, we must get down to brass tacks. The posters have been distributed, and they’ll be up by tomorrow.’

‘What is on them?’

‘Well, your photograph, of course,’ Captain Watkyn replied dreamily. ‘And underneath that they say: “Vote for Fen and a Brave New World”.’

‘I scarcely think—’

‘Now, I know what you’re going to say.’ Captain Watkyn raised one finger monitorily. ‘I know just exactly what you’re going to say. You’re going to say that’s exaggerated, and I agree; I’m with you entirely, make no mistake about that. But we’ve got to face it, old boy: these elections are all a lot of hocus-pocus from beginning to end. It’s what people expect. It’s what people want. And you won’t get into Parliament by saying: “Vote for Fen and a Slightly Better World if you’re Lucky”.’

‘Well, no, I suppose not… All right, then. What about the leaflets?’

‘I have some here.’ Captain Watkyn groped in his pocket and produced a handful of primed matter, which he passed to Fen. ‘The Candidate Who Will Look After Your Interests’ it said on the outside.

Fen studied it bemusedly, while Captain Watkyn went off to get another round of drinks.

‘You’ll like that, I know,’ Captain Watkyn said complacently on his return. ‘It’s one of the best things in its line I’ve ever done.’

‘But all this… it isn’t what I wrote to you.’

‘Well, no, not exactly what you wrote to me,’ Captain Watkyn admitted. ‘But you see, old boy, it’s no use trying to stray away from the usual Independent line: you’ll get nowhere if you do.’

‘But what is the usual Independent line?’

‘Just Judging Every Issue on its Own Merits: Freedom from the Party Caucus: that sort of thing.’

‘Oh. But look here: this says I advocate the abolition of capital punishment, and really, you know, I’m not at all sure that I do.’

‘My dear sir, it doesn’t matter whether you do or not,’ said Captain Watkyn with candour. ‘You must rid yourself of the idea that you have to try and implement any of these promises once you’re actually elected. The thing is to get votes, and with an Independent candidate you have to fill up election pamphlets with non-Party issues like capital punishment, because the only thing you say about major issues is that everything will be Judged on its Own Merits.’

‘I see. Then when I make speeches I have to stick to these non-Party things?’

‘No, no,’ said Captain Watkyn patiently, ‘you mustn’t on any account do that. You must talk a great deal about the major issues, but you must keep to pious aspirations, mainly.’ An idea occurred to him. ‘Let’s have a test. Imagine I’m a heckler. I say: “What about exports, eh? What about exports?” And your reply is—’

Fen considered for a moment and then said:

‘Ah, I’m glad you asked that question, my friend, because it deals with one of the most important problems facing this country today – a problem, I should add, which can be only imperfectly solved by any of the rigid, prejudiced Party policies.

‘“What about exports?” you say. And I reply: “What about imports?”

‘Ladies and gentlemen, there is no need for me to talk down to you. Politics are a matter of common sense – and common sense is that sphere in which ordinary men and women excel. Apply that criterion to this question of exports; cut through the meaningless tangle of Party verbiage with a clean, bright sword. And what do you find? You find that exports mean imports and imports mean exports. If we wish to import, we must export. If we wish to export, we must import. And the same applies to every other people, of whatever race or creed. The matter is as simple as that.

‘“Simple,” did I say? Yes, but vitally important, too, as our friend so rightly suggests. All of us want to see England prosperous; all of us want to build for our children and our children’s children a future free from the hideous threat of war. And I’m sure you won’t consider it a selfish aspiration if I say that all of us would like to see a few years of that future ourselves. And why not? It’s a great ideal we’re fighting for, but it isn’t an impossible ideal…

‘Ladies and gentlemen, the world is at the cross-roads: we can go triumphantly forward – or we can relapse into barbarism and fear. And it is for you – everyone of you – to choose which way we shall go.