По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

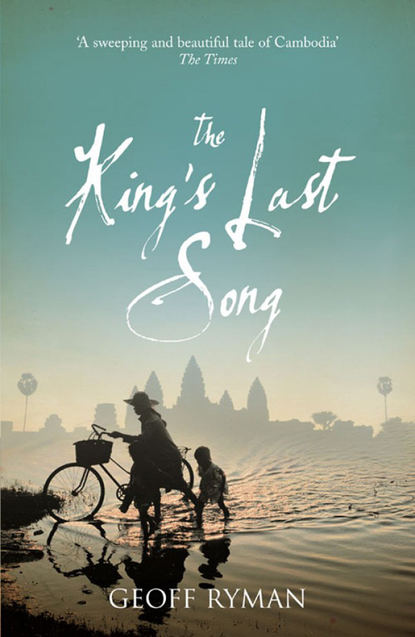

The King’s Last Song

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The boy sompiahed, yes. ‘My guru says I must learn humility.’

The King chuckled. ‘A strange way to show humility, to wake up a king with demands.’ The boy went still and looked down.

Impossible to gauge, little fellow, how much of a danger you will be. But what a heart you have. A brave heart and a good heart, to care so much for a slave girl. ‘All right. I will order it.’

The boy flung himself face-down onto the stone. Then the little imp sat up and made sure the King remembered. ‘Her name is Fishing Cat. Mount Merit.’

The King nodded. He stood up. His chest had sagged, his belly swelled, his calves had shrivelled. He shuffled into his sandals. ‘Come along, little fellow, I will get you past the guards.’

‘Don’t punish them,’ said the boy, suddenly alarmed. ‘I am very small and quiet.’

The King had to laugh. The boy’s heart is a kingdom; it could contain everyone. He cares for guards! They would kill him at a nod from me.

‘I won’t punish them,’ promised the King.

Suryavarman quickly calculated. Little Buddhist, you have ten more years before you become a danger. By then, I will be dead. With all this sudden trouble over my wife’s brother in Champa and with the Vietnamese in the north, someone somewhere will betray me soon. And so I know who you are. You are the danger to whoever is my successor. You can be my harrow.

If you love me.

‘Can I tell you who you are?’ Suryavarman said, as they walked. ‘Your father is my first cousin. Your mother was from Mahidharapura, the same pastures from which my own family came.’ His hand on the boy’s shoulder pressed down hard. ‘So I am fond of your family, that is why I asked especially for you to be here. Really.’

He nearly laughed aloud again; the boy’s eyes were so completely unfooled.

‘That is why I said you are my father,’ whispered the boy.

‘But now I will remember you as the boy with the good heart. You know the greatest pleasure in being King? It comes when you know you have done something good.’ Suryavarman mounted his kindly, regal countenance. It was a heaving great effort.

The boy narrowed his eyes and considered. You’re not supposed to think, lad, about what the King says. You’re supposed to agree.

‘Yes,’ the boy said. ‘Yes. That must be the greatest pleasure. That would be the whole reason to be King.’

‘Yes, but bees make honey, only to lose it. Are you good with a sword, young prince?’

The boy seemed to click into place. Good heart or no, he had a man’s interest in all things military. ‘I’m better with a bow. Better with a crossbow on an elephant’s back. Swords or arrows, the thing is to have a quiet spirit when you use them.’

Oh, yes! thought Suryavarman. You will be my revenge; you will be my scythe. I pity the poor cousin who succeeds me.

‘I want to train you specially,’ said Suryavarman. ‘In the art of war.’

Everyone learned how the beardless Brahmin’s scheme had backfired.

Why exactly the King favoured his cousin’s son no one knew. A cousin’s son was there to be held hostage, ground down, watched and limited. Not raised up.

Instead, the King demanded that the case be taken up by the Son of Divakarapandita himself, who had consecrated three kings. This highest of the Varna was to go to the consecration personally and ensure the foundation was well done, and it was said, ensure that the slave girl had the right to return to her own home.

Some of the Brahmin said, see how the King listens, he is making sure they are separated.

Then why does the King show the boy favours? He gave him a gift of arrows, and sent him to train two years early. And why were the palace women – wives and nannies, cooks and drapers alike – all told to let the boy and the slave girl be friends?

The only one who seemed mutely accepting of these attentions was the Slave Prince himself.

The rumour went round the palace that on the night before the slave’s departure, the Prince had called for a meal of fish and rice to be laid on a cloth, and invited the girl Fishing Cat to share it with him.

The girl had knelt down as if to serve.

‘No, no,’ Prince Nia said.

But he could not stop her serving. She laid out a napkin, and a fingerbowl.

He reached up to try to stop her. ‘No, don’t do that.’

Cat’s sinewy wrists somehow twisted free. Out of his reach, she took the lamp and lit scented wax to sweeten the air, and drive away the insects.

‘Leave the things.’

Fishing Cat looked up with eyes that were bright like sapphires. ‘I want to do this. I won’t have this chance again.’

‘Don’t be sad. We will always be friends,’ he said. ‘I will still hear you talking inside my head. I will ask how should a king behave, and you will say, how am I to answer that, baby? And I will say, with the truth. And you will say, the King should not lie like you do. And you will remind me of the time I hid my metal pen and made you look for it. It will be like we are still together.’

‘But we won’t be.’

‘Huh. You will not even remember the name of the palace or one of its thousand homeless princes.’

Both her eyes pointed down. ‘I will never forget.’

The Prince teased her. ‘You forgot the name of your home village.’

‘I was a child.’

‘You are still a child. Like me. We can say we will always be friends and believe it.’ He smiled at this foolish hope.

Then Nia jumped as if bitten by an insect. ‘Oh. I have a present.’ He lifted something off his neck. ‘Soldiers wear these into battle. See, it is the head of the Naga. It means no harm can come to them.’ He held it up and out for her.

‘Oh, no, Nia, if I wear a present from you, I will be a target.’

‘Ah, but no harm can come anyway.’

‘It is for a well-born person.’

‘Like kamlaa warriors, who go to their deaths? Look, there is no protection really. It is just something to have. You don’t have to wear it. Just keep it.’ He folded it into her hands. ‘When you have it you will think, I had a friend who wished that no harm could come to me, who wanted me to know my parents.’

Cat looked down at the present and it was as if he could feel her heart thumping. I wanted to make her happy and now maybe she thinks I have sent her away.

‘Fishing Cat,’ he said, holding onto her hand. ‘I stand waiting with all those kids who hate each other, and I think of my last day at home. I was being taken away, and I was sad and frightened, but everyone in the house kept smiling. They had to look happy or risk being thought disloyal, but I didn’t know that. My mother was allowed to kiss me, once. She whispered in my ear instead and she told me, “We did not ask for this. We are not sending you away. I will think about you every day. I promise. Just when the sun sets, I will think of you.” So whenever the sun sets, I know my mother thinks of me.’

Fishing Cat thinned her mouth trying to be brave. The Prince said again, ‘I am not sending you away. I will think of you every day. I promise. Just as the sun sets.’

A slave cannot afford unhappiness for long. Cat managed to smile. ‘I will think of you too, Nia. Whenever the sun sets. I will tell my parents about you, and how you brought me back to them. I will ask them to offer prayers for you.’

Другие электронные книги автора Geoff Ryman

Lust

0

0