По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

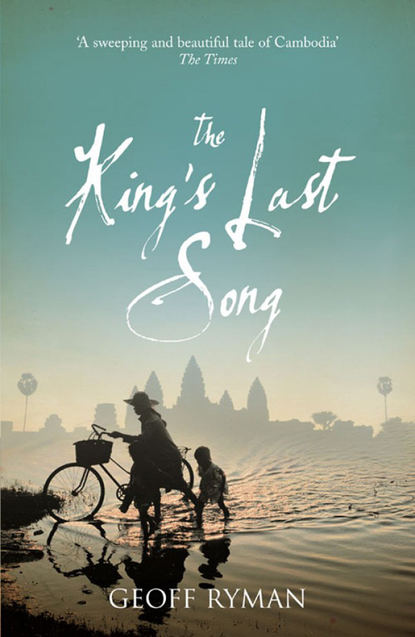

The King’s Last Song

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Aren’t we a dump of a country? Other places have spy satellites and missiles, we have angry little men and fists and rooms in the back. Doesn’t mean to say it doesn’t hurt.

There are certain satisfactions in life. One is not waiting until you are hit first. Another is hitting them hard out here in the motel light, where everybody can see that it’s eight to one.

Map kicks the knee of the guy closest to him. The guy sinks. Map head-butts the guy who was trying to sneak around behind him.

Then Map takes off. He runs, but to the right, not to the left towards the gate and his bicycle. He tears away, right and then around the back of the building.

My legs are my sons. He can hear their shoes on the gravel spurting off in the wrong direction and doubling back. You thought I’d go for my bike, but I’m going where there are no lights and I can make a straight run for the fence. You got razor wire round the top? That’s why I’m going for it.

Map is gleeful. It will take them a minute to find the perimeter lights. He sprints blindly in the dark for the fence. He hears shouting and whistling. Dogs. Sure they got dogs, I can outrun dogs and it’s a still night, no wind. There’s the moon, and he thinks this is fun too; he’s grinning down.

This is like the gang wars with the arrows when I was a boy. This is what I’ll do when I die. They’ll try to send me to hell, and I’ll climb up the fence to heaven anyway.

Fingers into mesh, and I hear the paws, the lovely padded paws of dogs. They’ll jump at the fence, so scamper Map, scamper like the day they told you Mom was dead and you ran away and forgot that they’d told you that. It’s vines, Map; you’re climbing vines, back to Mom, back to your brother, back to everybody.

The dogs bark, and here’s the wire.

Lightly as possible, as if vaulting on a hot skillet, Map pulls himself over the razors. They tear his hands and legs but he knows there will be leaves on the other side to wipe them clean.

I always shoot better with sliced fingers anyway.

You think I’ll stay on the roads for you? You think I’m not a local boy, so I don’t know how to keep out of sight?

The dogs are going crazy, they’re making hound music, and the big lights have snapped on and maybe you see me in pale light like a ghost, maybe you’ll shoot, so I’ll just duck behind the old TV station that’s empty now, like an empty snail’s shell.

The road.

Map starts to laugh. He imagines Lieutenant-Colonel Rith, swearing and stomping up and down. He imagines the guy whom he head-butted holding his bloody nose. Oh man, will they be after my liver for this! I’ll be sleeping rough on the moon after this! I’ll sleep under the hay! They’ll chase me everywhere; I’ll just be a ghost.

He darts across the scrub field towards the dry flood canal that roaring waters had gouged so deep.

Overhead the crazy moon laughs. Map laughs too. He’s home.

Map loves war.

Luc is on a boat.

It’s made of overlapping timbers, so water slops and gurgles against the hull with a noise like musical springs. The floor of the hull stinks of fish and is ribbed with joists that aggressively dig into buttocks, kidneys, ankles, and hips. Luc is jammed under the low deck. It’s impossible for him to sit up, let alone stand.

Tape covers Luc’s mouth and eyes; his legs and wrists are lashed with the sort of bungee cords that hold pigs and hens in place on motorcycles. He can do two things: hear and smell.

Outside, marsh birds warble, whistle or keen. Frogs make their odd beautiful sound like a cross between a gong and a flute. The boat rocks continually, and he can hear wind in reeds, so they are somewhere on the shores of the Tonlé Sap. Next to him, the General keeps groaning through the tape.

Luc smells cigarettes and fish being kebabed on the deck above. He hears the slosh of drinking water in a bottle; he hears boys making light and friendly chatter. Then one of them hisses and everything goes still.

Another boat putters towards them. The silence is long except for one whispered question. Then a calm voice calls clearly across the lake. The boys chuckle with relief and shout; feet thump onto the deck and there is hearty laughter.

A rough voice barks. ‘You should have seen it! It was a sight. They all thought the Khmers Rouges had come for them again! The whole town was running away. We shot a few extra bullets here and there to add to the party, and then all the power went, like it does every New Year, and all the women screamed.’

‘New Year, let them remember New Year!’

‘Happy New Year!’

‘Well, let’s have a look at our prizes. I want to see their eyes.’

More feet thumping, and a rough sound of wood sliding. ‘Whew! You guys stink!’

A padding of feet and a tugging at the tape over Luc’s face. Suddenly, with a ripping sound, it’s torn away, taking Luc’s eyebrows with it. Thank heavens, he thinks, that I keep my hair cut short, number one buzz cut. Torchlight blazes like sunlight into his eyes. He blinks, dazed. The torchlight becomes beautiful, like a star fallen to earth, surrounded by a corona.

‘Welcome to Siem Reap Hilton,’ someone says in accented English.

Luc squints, dazzled by the light. Don’t look at their faces! He turns his head away and sees the General’s bloodhound face – heavy and crumpled, with dark, wounded eyes.

The same barking, exuberant voice says, ‘Hey General, you must have thought everything was going the way you like it. Welcome back! Make yourself at home here in the hotel. We have everything! Food, water, a comfortable bed. Guns.’

The General stares heavily and says nothing.

They’re showing us their faces; they don’t care if we see them. That’s bad. Before he can stop himself, Luc looks up, eyes now adjusted to the light. He sees the face of an older Cambodian man. Luc’s eyes dart away, but not before he realizes that he knows the face. From where?

The older man berates him in English. ‘Barang. Welcome to the real Cambodia. Lots of mosquitoes. No air conditioning. Real Cambodian cuisine.’

Unceremoniously, a whole burnt fish, small and bony, is pushed into his mouth.

The man has a competent face, the face of an old, tough businessman. He looks like he runs a shoe factory. He’s wearing half-moon spectacles and Luc tries to remember where he has seen those before. The eyes are wide, merry, glistening, yellow splotched with red. The teeth are brown and broken, framed in a wild smile. It’s not a face I’ve seen smiling. That is why I cannot place it.

Luc feels sadness for the world. This is a world of roses, forests, rivers, and wild animals. It is a world of mothers and children and milk. How do we get so wild-eyed, so anguished, and so cruel?

Luc, you are already a dead man.

‘Chew it, barang, the fire’s burnt all the bones. They break up in your mouth. It’s more than we have to eat most nights. It’s New Year. A celebration.’

The old man switches to Khmer. ‘You too, General. Without us, you wouldn’t have a job to do. Eat!’

A head appears through the trapdoor and warns, ‘Lights!’

The smile drops and the face settles into its usual immobility. It looks numb; the mouth swells as if novocained. The staring, round eyes are encircled by flesh. Fish Face, Luc thinks.

Fish Face says, ‘Ah, make a lot of noise, wave the fish at them, wish them Happy New Year.’

With the smile gone, Luc recognizes who it is.

‘If they don’t go away, shoot them!’ Fish Face jabs a casual thumb in Luc’s direction. Then he sniffs and pushes the tape back over their mouths. Luc needs to spit out the bones and can’t. He can’t swallow either. The bones and half-chewed fish plug his mouth.

Fish Face wrenches himself round on his haunches and as if levitating shoots up and out through the trapdoor.

Luc remembers the farmer in whose fields they found the Book.

Luc tries to remember everything Map had told him about the man. He had been Map’s CO for a while.

Другие электронные книги автора Geoff Ryman

Lust

0

0