По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

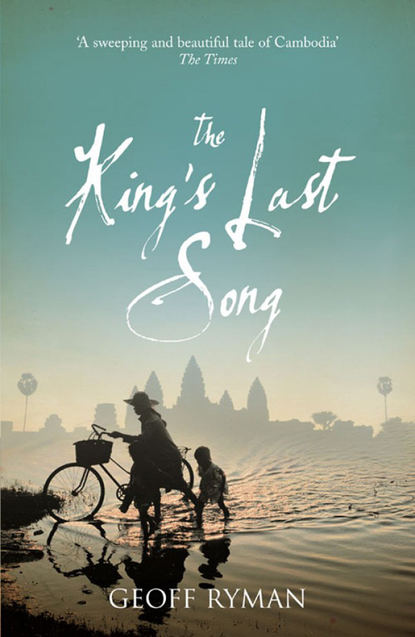

The King’s Last Song

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Prince said, ‘I know it takes a lifetime to learn how to make observance. I think it is hard work to parade on an elephant and look like something that talks to gods. Harder still to look like you will become a god when you die. Hard work, but that is not enough.’

The old man blinked. ‘It isn’t?’

‘I once had a friend. She was a slave, a gift to this house. I saw that her world was as big as our own. I saw that whatever was holy in us was also holy in her. I think we try to climb towards the Gods. We get higher and higher up to the King, and then over the King, to the Gods, and when we look at the Gods, we find … what? A cycle? Back down to the flies and the fishes. There is no top. Everything is holy.’

The old man disapproved. ‘A radical notion. What do you know of the Buddha?’

‘Almost nothing.’

‘Oh, tush!’

‘He was a teacher great enough to be treated almost like a god.’

‘And what did he teach?’

‘Virtue. I am to be a soldier, and I will be a good soldier. I will serve with honour, and courage and efficacy.’ The Slave Prince clenched his fist. ‘I have no doubt of that. But what I want, if anyone should ask, would be to be a Brahmin.’

Divakarapandita chuckled and waved a hand.

‘A Brahmin who rides an elephant and fights for his King when the time comes …’

‘Oh ho-ho!’

‘And who is not ignorant.’ The words were hot, they made his eyes sting.

Divakarapandita’s mouth hung open. ‘Ignorant?’

‘I know nothing!’ Then less heated. ‘Nobody has bothered to teach me.’

‘Do you think anybody has bothered to teach the Lady Jayarajadevi!’ The Consecrator looked appalled. ‘You have to teach yourself!’

Nia hung his head. ‘I speak heatedly from shame.’ He began to see what the interview might be about. Another round of matchmaking. Who was this Lady to have the Consecrator concern himself with her marriage?

‘So you should be ashamed.’ But the old man seemed to say it from sorrow. He touched the Prince’s arm. ‘You have no ambition to be King?’

‘Toh. All these little princes, all dreaming of being King, all making tiger faces at themselves. I want to be a holy warrior.’

The old man stopped, shuffled round to face him, took hold of both the Prince’s arms, and stared into his eyes. ‘War is never holy,’ he said. ‘War makes kings, and kings perform holy functions. But the two are separate.’

Nia felt shame again. He hung his head. ‘I feel things. But I don’t know things.’

‘Maybe there is someone who will take the time to teach you,’ said the holy man. ‘And then you might become what you want to be, a wise man.’ He drew himself up. ‘What will you do when the King dies?’

Nia felt alarm, for himself, for his whole life. ‘The King is ill?’

‘Ssh, ssh, no, but he is a man. What will you do when he dies?’

Nia thought. With his protector gone, with the Oxen fighting over kingship, there would be years of violence. He imagined Yashovarman, and found he felt disgust and alienation and fear. ‘It depends how he dies.’

‘How do you mean?’ The holy man’s eyes were narrowed.

‘If someone murders the King, then I will seek justice. If he dies in his bed, that’s different.’

The old man looked up and then back. ‘There is a war coming,’ he said. ‘In Champa and in the lands beyond. You will be sent away and may not come back. You are sixteen and it would be good if you were married. You see, Prince, you are as dear to Suryavarman as the Lady Jayarajadevi is to me. We have discussed a marriage between you and the Lady, the King and I. I have assessed you and find you as the King described.’

The Dust of the Feet drew up his robes. ‘The marriage will proceed,’ he said.

It was only the marriage of a high lady to a prince whose lack of family was made up for by his own subtleties of person.

But not only the Dhuli Jeng, but the King himself were to attend. It was to be held in a pavilion in the royal enclosure. The greatest soldier, Rajaindravarman, General of the Army of the Centre, was to be the young prince’s sponsor, as his father was dead.

And since this prince was already in line for a small throne, the Dhuli Jeng was to recognize him at the same time as a little king. He was to take his title.

The princes and the princesses all washed exuberantly around the cisterns. There were to be musicians and dancers. This was a chance for the King to express his love. A general sense of satisfaction emanated from him and was communicated to his loyal court. They were to be joyous before a time of war.

The Slave Prince was married wearing his quilted flowered coat, and carrying his shield. A crown of bronze had been wound into his hair. As always, he did without his torque, which gave immunity from harm.

Nia marched with a column of his comrades in arms. His friends looked pleased. They passed through the well-wishers and then climbed the steps to the pavilion.

Torches fluttered in the wind. Pressed around were wives of the King, high courtiers, and a few members of Jayarajadevi’s family.

The nephew-in-law of the childless King was there. Prince Nia saw in the eyes of Yashovarman something measured and measuring. He is not an Ox, that one, thought Nia. He may have been one once, but now he simply uses them. How wise he was, to marry the King’s niece. The certitude came. He will indeed be Universal King. As he advanced, Nia sompiahed particularly to him. Yashovarman blinked in surprise, and indicated a return of respect.

So that Jayarajadevi could in fact be married to a little king, the title-giving came first. Consecration was too high and holy a word for it. The Universal King would recognize the new title and the Little King be given a chance to swear loyalty.

So the Dhuli Jeng was to give out one more regal honorific. Which was to be?

The Prince smiled. He had thought long and hard about this. Once he took his title, then his bride might have to give up or amend her own if their titles clashed inauspiciously or gave obeisance to different principles. Why should she change her great name? His smile widened as he said, ‘My name is Jayavarman.’

He had taken a name to match his wife’s and not the other way around. The onlookers murmured among themselves.

It was a better title than Nia, but Jayavarman was also the honorific of many Great Kings. Did it show ambition? Suryavarman’s countenance did not flicker.

Divakarapandita’s smile widened a little further. The overturning prince had overturned again. ‘You are now Jayavarman of the City of the Eastern Buddha.’

Little King Jayavarman beamed as he swore loyalty to the Universal King.

Then he was married.

Indradevi Kansru held up an embroidered cloth so that the Little King could not see the beauty of his bride too soon and then be dazzled speechless or struck blind. Indradevi was so pleased for her sister that a whole night sky seemed to beam out of her eyes.

Divakarapandita himself scattered flowers, and poured water on the stone lingam and yoni. The embroidered cloth still stood between them.

My wife, thought Jayavarman. Behind that cloth is my wife. I shall be a husband, we will be together, we shall make love, we shall be each other’s support, and we will have children, brilliant babes.

Divakarapandita beckoned him forward and the Prince knelt and drank water, sign of everything, source of everything, as poured from the yoni. Unusually, making some obscure point, the Dust of the Feet asked him to drink from the lingam as well.

Then the cloth was lowered.

Другие электронные книги автора Geoff Ryman

Lust

0

0