По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

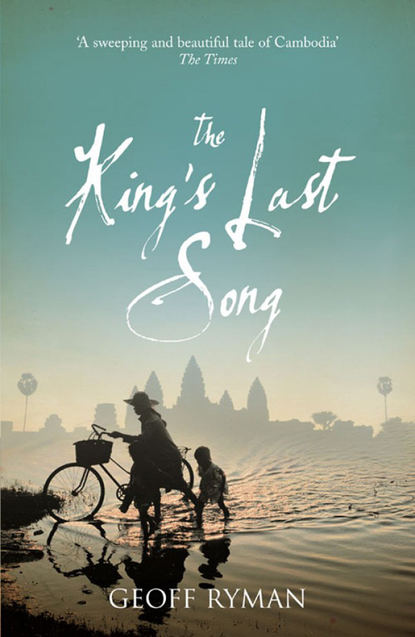

The King’s Last Song

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

No it wasn’t.

Luc feels the dark.

You know what this is, Luc. So does Arn; his expression is full of both love and awareness. It is kindly but not exactly innocent.

Oh God, this is what it is. I am that. That thing.

He looks at Arn, his gently burnished face, and accepts. If it means I get Arn, then yes. Yes I am. That is me. I am that thing. And right now, nobody can see, and if they can see I don’t care.

Suddenly Luc shouts like John Wayne, and drives the pedals even harder and faster, and Arn chuckles and laughs. Luc lifts his feet off the pedals and just for a moment, he is flying.

In those days Boeung Kak Lake was a park that people could stroll around. Luc and Arn arrive and Arn’s friends cluster round to laugh and joke about the spectacle of a barang pedalling a cyclopousse. The laughter is good-natured. It’s New Year, you get to do crazy things. The two men … boys … are sent on their way with good cheer by the other drivers who agree to look after Arn’s machine. Arn goes to the latrines, but not to relieve himself.

He changes into his white shirt, and his perfectly creased khaki slacks.

They head out for the park, full of prostitutes at night, but families by day. Halfway to the lake they are pelted with water balloons by a gang of kids. They are nice kids, boys and girls all about fourteen, so Arn and Luc just laugh. They walk along the pier and all the cubicles are taken. Well they would be full, wouldn’t they, it’s April 13

.

Luc sighs. ‘We can always go back and sit on the grass.’

Except that the very last little cubicle, right at the end of the walkway out over the lake, is empty. Maybe nobody persevered all the way to the end of the pier; maybe a family has just vacated it. But there it is – hammocks and a charcoal stove and a view of the little lake, with its lotus pads and dreamy girls and serious boys in canoes.

Heartbreak time. Arn has bought them lunch, bundled up his kramar. The kramar serves as his pyjamas, his modesty patch, his head-dress, and his shopping bag. He unties it carefully, gently and there is sticky rice in vine leaves, soup in perfectly tied little bags that have spilled nothing, pork in sauce with vegetables.

Luc tells him it is a wonderful lunch and they sit and talk about the usual things. And Arn becomes overwhelmed. Because his unlikely dream has come true. The huge beautiful kindly barang is his.

‘Luc, I want to study,’ he says as he eats. ‘Luc, I am so happy. I know life will be just great. Everything in Cambodia good now. We have our Prince. Your people good to us, but the politicians go home, so now we can be friends.’

Arn sways from side to side as if to music as he says, ‘We all live together and work hard, so Cambodian business, Cambodian factories, Cambodian music, all do very well now. We will become modern country. We join the world as friends.’

‘Modern country,’ says Luc and lifts his hand as if raising a toast. ‘Friends.’

It is April 1967 and rice exports have collapsed and the news says that in a place called Samlaut, somewhere near Battambang, the peasants are in revolt. The Prince blames Khieu Samphan and the communists.

For now the old French song keeps singing in Luc’s head. Lovers, the lyrics tell him, don’t fear for tomorrow.

Arn would be fifty-eight now, thinks Luc waking up in a tent in the dark, reeking of insect repellent. Where is he?

Whenever Luc visits Phnom Penh, he peers at the moto-dops and elderly motoboys. He scans bus windows, taxis and stalls in the Central Market. Most likely Arn would be using a different name now and his face would be changed. Arn could be bald, fat, or sucked-dry skinny. But most likely … well …

One out of three men died.

Leaf 35

April is when the red hibiscus announces the change of seasons like the musician blowing his conch. April is after the harvest and before the rains. April is when the ox-cart falls back, lifting its long neck to sniff the wind. The oxen sleep under the house. Inside it people sleep or dance. Season of rest, season of labour, April is when we hoe the earth to guide the waters like children to their beds, making straight canals to bear new stone. April is when we lay courtyard pavements. The people kneel and drop the stones like eggs. They hoot like birds and bellow like elephants and laugh and start to sing. April is when we bear the temple stones up the ramps and rock them to sleep like uncles. Season of war, April is when the generals make one last effort before the rain to press on with the campaign. April is when we create. April is when we destroy.

April 13, 2004 (#ulink_400ca348-cdfb-50a1-8502-ffd25ce6ea80)

April is the Time of New Angels, just before New Year.

Old angels will be sent back to heaven. They will be replaced by new angels who take better care of mortals.

On the morning of April 13 2004, the year of his retirement, King Norodom Sihanouk himself visits Army Headquarters in Siem Reap to view the Golden Book.

He gives the Book its Cambodian name: Kraing Meas, which means something like Golden Treasure. Photographs are taken of the King standing in front of a green baize background with leaves from the Book balanced against it. He shakes the hand of General Yimsut Vutthy.

The National Museum is determined that the Kraing Meas should come to rest in Phnom Penh, but there are high politics involved. Sihanouk has a house in Siem Reap. Prime Minister Hun Sen does not. The King himself has argued that neither APSARA nor the National Museum are secure enough to display such a treasure. Perhaps the Book could be the centrepiece of the much-needed museum in Siem Reap?

The Book would be repaired by none other than the royal jeweller, a man much experienced in gold and in repairing artefacts including, it must be said, stolen ones.

The Siem Reap regiment would have responsibility for transporting it. They too want the treasure to come back to the town. Most of the regiment’s many generals have invested in hotels there.

Most particularly General Yimsut Vutthy.

So on the last day of New Year Professor Luc Andrade packs a small overnight bag, pays Mrs Bou who runs the Phimeanakas Guesthouse and tips the staff.

The Phimeanakas security guard helps Luc out with his cases, including a large, empty metal case, usually used to transport film cameras. National Geographic has loaned it to Luc in return for favours. It is lined with shock-absorbent black foam.

He gets in a taxi and makes the short drive to the Regiment’s headquarters, feeling reasonably content. He has told no one about the arrangements, not Map, not William, not his Cambodian dig director. He had tried to tell the Director of APSARA, who just laughed and waved his hands. No, no, don’t tell me; I don’t want to know.

Luc will be the Book’s escort during the flight. It must be because he clearly belongs to no Cambodian faction. Which may be why he was not invited to the royal viewing this morning.

He sees the fine new Army HQ. From a distance it looks like a Californian shopping mall in the Mexican style – long, low buildings with red-tiled roofs. Closer up, Luc can see the roofs slope upwards and the tips of the gables reach out like the white necks of swans.

A chain is lowered, the taxi turns crackling into the huge gravelled forecourt. Along the mall, individual offices line up like shops each with its own door and blue-and-white sign in Khmer and English: Infirmary, Operations Office, Intelligence Office.

One of the doors is open. It does not have a sign, but Luc knows it is the General’s office. Soldiers stand crisply to either side of it, and murmuring emerges from it.

Luc walks on, carrying the metal case, accompanied by a soldier.

The General’s office runs the depth of the building and is crammed with military men. They throng around canapés and cognac laid out on tables. The seats are huge heavy wooden benches that look like thrones and make your bottom ache. The wooden floors gleam, and there is a bank of TV and DVD players on shelves.

Right on top of the General’s desk is the Book itself, spilling somewhat loosely out of its ancient linen and pitch packaging. Some of the gold leaves are out of order, resting on thumbtacks on the baize. Two days’ work, calculates Luc, just to find out where they belong.

The General greets Luc like an old friend and jokes, ‘In the old days, people would call me a Cheap Charlie for not offering cigars, but now CNN says they are bad for your health.’

Luc knows much more about Yimsut Vutthy than the man would care for. Luc knows which hotels he has invested in and who his Thai and Singapore partners are. He knows roughly what percentage he takes from the forty- to sixty-dollar fees tourists pay to enter Angkor Wat, for the General is a protégé of the establishment, someone of whom Sihanouk himself would be wary. Yimsut Vutthy is a compromise candidate.

A player, in other words.

The General introduces a number of Army officers and civil service functionaries, all of whom want to be associated with the Book

‘You see,’ one of them says, ‘we take the safety of the Book very seriously.’

Luc cannot stop himself smiling.

They crowd round to look over Luc’s shoulder as he packs away the Book, still in its sections of five leaves. The measurements were correct and the sections fit with serendipity into the slots, gripped in place by the foam padding.

Другие электронные книги автора Geoff Ryman

Lust

0

0