По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

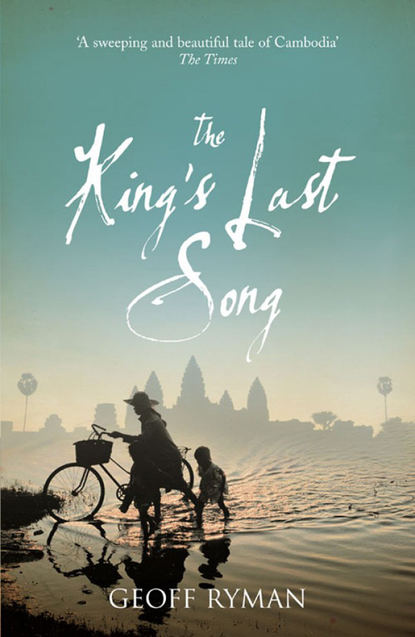

The King’s Last Song

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Then everyone toasts the health of the King and Mr Hun Sen. Canapés have done little to absorb the alcohol. Hungry and slightly fogged from cognac, Luc glances at his watch, anxious to get going.

Later than he likes, Luc and the General walk out to a waiting Mercedes. It takes two soldiers to load the now heavy case into the boot. The General holds out an expansive arm for Luc to precede him into the car. Luc smells the soft tan leather upholstery, and runs his hands over it as he slides into place.

Two motorcycles roar ahead of them. Almost inaudibly, the Mercedes eases out behind them, with an Army jeep following. Feeling presidential, Luc settles back with relief as the cavalcade pulls out of the gates.

Conversation with General Yimsut Vutthy soon runs out, but Luc has ready that morning’s Herald Tribune. Rather gratifyingly, if well into the middle pages, the paper reports the Book’s discovery. GOLDEN BOOK HOLDS KEY TO CAMBODIAN HISTORY. An official press photograph shows the General himself displaying the leaves on a wooden table. Luc passes the newspaper to him.

Then very suddenly Luc is sure he has left behind his passport and letter of contract to the Cambodian Government.

With a lurch of panic, he reaches down for his belt pouch. He has time to feel his passport and papers securely inside.

The car swerves. In his slightly befuddled state, Luc thinks the veering has come from him.

Tyres squeal; metal slams. Inertia keeps Luc travelling forward, folding him against the front seat.

An accident. Luc struggles his way back into his seat. He sees an angry face against the window.

Luc behaves entirely automatically. There’s been an accident, someone is upset, so go and see if you can help.

He opens the car door.

The angry man seizes him, pulls him out of the Mercedes, spins him around and pushes him forward. Luc stumbles ahead in shock.

A new silver pick-up gleams by the side of the road. New, Luc thinks, and probably rented. Very suddenly, as if a tree trunk had snapped, there is a crackling of gunfire behind him. This is it, he thinks, this is really it. He’s absurdly grateful for his belt pouch. He’s thinking that it will hide his passport and money. They’ll only get the twenty dollars he keeps in his pocket.

The back of the pick-up truck is down. Someone shoves him towards it. Other hands grab him, hoist him up and then slam his head down onto the floor. He hears a ripping sound and he realizes that heavy workman’s tape is being wrapped around his head. It blacks out his eyes and covers his mouth. Something like a heavy sack is thrown against him. It groans. Luc recognizes the General’s voice. A light, rough covering is thrown over them both; Luc smells cheap plastic sacking.

Someone shouts urgently. A bony butt sits on the most fragile part of his ribcage. The engine revs and the truck jerks forward, bouncing over ruts and slamming the metal floor against his shoulders and head. The truck swings back around on to pavement and accelerates away. Luc assumes it has U-turned back towards town.

The strange things you think when you are in trouble. Luc finds he is worried about the duct tape pulling off his eyebrows and jerking out his hair. He thinks of Mr Yeo and wants to tell him, see how brave I’m being? He thinks of his mother. See Maman? I don’t feel any fear at all. This is bad, this is very bad, but I’m not panicking. He wants someone to be proud of him, to sit up and take notice.

He remembers Tintin. Tintin always remembered how many turns, left or right, and the kind of terrain, and the kind of noises.

So he pretends he is in a Tintin comic book. As they whine along the airport highway he counts to sixty five times. Then they shudder over open ground to the count of sixty times twelve. After a couple of almost vengeful crashes over humps he loses count.

They slow to a stop. He smells dust and something else, metallic and sour, which he realizes is probably blood, his own or the General’s.

The back of the truck thumps down. ‘Out, out,’ someone says, ‘let’s go!’ Luc shifts, feeling his way out of the pick-up. He is seized, hauled out, and thrust forward. Stumbling blindly over the ground he thinks: I will have to learn Braille in case I ever go blind. Why did I wear my good shoes, they’ll be all dusty.

Well, mon cher, they will look very branchée at your funeral. OUCH the stones are like teeth jabbing through the thin soles. Scrub crackles, prickling ankles.

Luc hears the pick-up rattle back onto the road behind him.

Then his feet go out from under him and he slides down a dirt slope onto rocks. A wrench and a folding-under and he knows that his ankle is twisted. Someone crouches down on top of him. He hears sirens wail past on the road above them. We’re down a ditch, he thinks. A ditch or a channel for floods in the dry season. You’d need to know it was here. These are local people.

The sack is thrown over him again. Some tiny insect nips him. Daylight mosquitoes, they carry dengue fever. He tries to slap it, and realizes that he can’t – his hands are tied. He tries experimentally to talk through the tape.

‘You say nothing!’ The voice is so close to his face that he feels breath on his nose. An insect bites him again.

He tries to count how long they wait, but then Tintin loses his nerve. Very suddenly Tintin wants to go home.

You are local people. I’ve probably seen your faces. All smiles. Well Cambodia is smiling now, isn’t it? I can see it grinning at me.

See, Cambodia is saying, you thought you could love us out of ourselves. Well here it is. This is what everyone else in Cambodia went through. Do you love it now? See how powerful love is? How long did you think you could be in Cambodia and avoid this? How long did you think you could avoid the strong men, the gangs, and the armed ex-soldiers? This is Siem Reap on Highway 6, one of the most dangerous parts of Cambodia for most of the thirty years of conflict.

Your turn, Luc, to be in a war.

April 1142 (#ulink_bfb43757-f270-5380-8914-f59159e78861)

The teacher could not grow a beard.

This was a great sadness for him and probably an embarrassment for his students. The teacher was a Brahmin, originally from India, Kalinga. His people could grow beards. It was a mark of their holiness. This Brahmin wondered if he had sinned in a previous life. Or perhaps his beard refused to come because of his lack of courage. He was too lax with challenging the boys especially the one who called himself Prince Slave.

For the sake of my beard, the Brahmin promised himself, the next time Nia questions authority, I will put him in his place.

In the class they were discussing the ordering of castes, and Nia sighed and said, ‘There are no castes of people in Kambujadesa. In Kalinga, I’m sure these things hold firm, but here everyone is either a noble or some kind of slave.’

Now, the Brahmin thought, I must act now. ‘Do you deny the ordering of categories?’

The Slave Prince said with a sideways smile, ‘I am sure the categories are orderly in a country where everyone can grow a beard.’

The silence in the room was clenched.

Prince Nia continued. ‘Here everyone keeps telling us to support the ordering of categories and professions, but I can never tell if they are talking about Varna or Jakti. I don’t think they can either.’

‘Your problem, Prince,’ said the Brahmin, ‘is that you think words have no power. You use them too freely.’

‘I think truth has power. Words have power when they are pushed out of you by truth.’

‘You have no humility.’

The young prince paused. ‘Not enough, it is true.’

‘You should learn humility, Prince.’

‘That’s true too. From whom should I learn it, guru?’

‘From the King!’

‘There is no possibility of learning anything other than humility when confronted by a king. I find it more instructive to learn it from slaves.’

Like a clam, the jaw of the Brahmin slammed shut. Too, too clever, this Slave Prince. The Brahmin tried to humiliate him. ‘You speak of your little friend.’

‘She is my friend. She sweeps and scrubs and fans and whisks. But she has a loyal heart.’

Just lately, the Brahmin had noticed, the children were not laughing at Nia. The other princes hung their heads and looked sullen, hiding something. The Brahmin had a terrible thought. This Nia is recruiting them. Recruiting them to what? The Brahmin had no words, but he felt this overturning prince was an enemy of religion.

‘I think you learn pride from her,’ said the Brahmin.

Другие электронные книги автора Geoff Ryman

Lust

0

0