По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

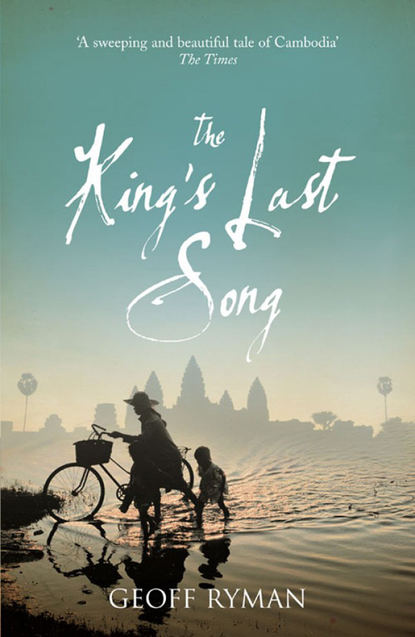

The King’s Last Song

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The cursed boy just looked thoughtful. ‘There is pride there, for I find her an exceptional person and so I am proud that she has condescended to be my friend.’

‘Upside-down boy! She is the slave, you are the Prince.’

‘So I should learn pride, not humility?’

He was a treacherous lake that made the boats unsteady.

‘You … you take pride and turn it into humility and then turn it into pride!’ The Brahmin knew that he sounded weak and shaken.

A danger, this one. This one is a danger.

Who knows what this danger to the Gods will bring? War? Famine? Drought? Severe lack of observance always brought the wrath of gods.

Even at twelve, this overturning Slave Prince must be brought down.

Shivering with the importance of what he was about to do, the teacher visited Steu Rau, the Master of the King’s Fly Whisk.

The Master’s family had whisked kings in public for generations. Family members had also been the Guardian of the Royal Sword and the Superintendent of the Pages. They were not Brahmin but they were definitely Varna. The Fly Whisks understood loyalty and the meaning of the categories.

Steu Rau agreed. ‘Yes, yes, you are right. You have no idea how this friendship unsteadies the palace girls. They keep looking for similar favours. Why, some of them have even offered themselves to me.’

‘Shameful!’

‘In the house of the King!’

The King was supposed to sleep with them, not the officers.

‘It is the singling out that is the problem,’ the teacher said. ‘The lower categories have to understand that they lack distinction, that they are as alike as cattle. That they earn distinction slowly, life after life, through obedience.’

‘This girl shoots up like a star!’

‘Through the attention of a capsizing prince. So. I think we must remove this attention by separating them. Permanently.’

‘Yes! Yes! Kill her!’

The Brahmin admired Fly Whisk’s energy. But he also thought that perhaps the girl might have offended Fly Whisk. ‘I do not think the killing of a female nia would earn merit. It might have the reverse effect.’

‘Humph! Well. You are the expert in these matters, guru.’

‘I think the King will be making donations of land to a temple soon, and that she should be one of the gifts. She should be donated to work in the fields. No serving in the temples. In other words, the attention of this capsizing prince will have resulted in a lowering of her status. It will have taken her even farther from heaven.’

The Master enjoyed the idea. ‘Yes, yes, that would be an object lesson. And a donation will earn merit.’

‘For all who are part of it.’ The Brahmin smiled and held up his holy, bestowing hands.

Suryavarman had many names, and would have another name after his death.

He slept each night at the summit of the palace temple. At least that got him away from his wives. Attendants had strung up his hammock and lowered draperies to keep out the night air. In the old days a woman might have been left with him, for the sake of form.

But the Universal King was old now. He did not want women with him. He did not like the way they searched his face and looked at his old body. He was exhausted with the impudent stripping gaze of everyone who saw him. They searched his face for signs of glory and found only a man after all.

And yet, what he had done! He was the Sun King, who had swamped his enemies. Might not a little of that show on his face?

Nowadays, Suryavarman turned might into merit. He had built the biggest temple in the world in honour of Vishnu and all the Gods. Perhaps doubt was the burden that gods lay on kings for coming too close to them.

You sluiced water around a stone, and claimed it was holy. You did not know whether it was or not. You never saw a god, or felt a god. At times you used the Gods strategically, to frighten or threaten or shame your rivals.

Sometimes you wondered if any of it was true.

At night, lying awake and listening to the sounds of insects, you would know: you were tough and strong but sometimes that strength crushed things you wished to keep. You had a mean streak, you had a fearful streak, and you had a mind that always played chess with people’s lives. You took pleasure in all the politicking; you promised yourself that you would stop. You tried to convince yourself that you had finally won and could afford to be more forgiving. Something in you prevented it.

Bigger and bigger temples, more and more stones piled high, more exiles, more confiscations, more setting families off against each other. And at night, loneliness.

Something fluttered in the shadows of the candle. It slipped around the draperies, like a gecko.

‘I am child,’ a boy said, and flung himself down onto the stone.

I can see that, thought Suryavarman and sat up. The boy must have avoided the stairs by climbing up the sides of the temple, on the carvings. ‘Have you ruined the stucco?’ the King demanded.

‘I took care to avoid doing harm, Great King. I am small and light. I do not come for myself, King, but for another.’

The King beadled down on him. ‘Whose son are you?’

‘Yours,’ said the boy, and then hastened to add, ‘in spirit I am yours, for I have grown up in your house, but my father is Dharan Indravarman, who serves you as a small king in the northeast.’

‘I know him,’ rumbled Suryavarman. My cousin, not particularly troublesome, a man of no obvious faults and a Buddhist, so doubly harmless. ‘You can sit up, I want to see your face.’

The boy was a plump little fellow only about twelve years old, with a big round face and thick peasant lips. No matter what he said, his serious, regarding eyes had no trace of real fear.

The King asked him, ‘What makes you think you are not in a lot of trouble?’

The boy replied, ‘Because you are a Universal King. A Universal King is brave and has faced terrible danger. Such a king would have no need to frighten me.’

‘You are troubling my sleep.’ Like bad dreams.

The little fellow bowed and crawled closer. Determined, wasn’t he?

‘King. You are generously setting up new temples, and you are to give to these establishments great gifts of land and water and parasols and oil and wax and people.’

‘Yes?’ Dangerous stuff, little fellow, for these gifts are the canals of politics. Gold and silver and obligation flow down them. And blood.

‘There is a slave girl. Her name is Fishing Cat. She was honoured to be made part of our household when she was five. She is so happy to be here, she has not thought of her village since. She does not even remember its name. But I have checked the records and I see she must have come from the villages near Mount Merit. If …’ Here the child faltered, bit his lip, became a child again. ‘If that is where you are planning a temple, then perhaps if she is sent there, that would be a good thing. She could see her family again.’

‘Is that all you want?’

‘I have been very foolish,’ said the child in the tiniest possible voice. ‘I became friends with her. It was easy for me, it was fun. I had no thought of the danger for her. It is my fault, but she is the one being punished.’

The King could not help but smile. ‘You climbed up here for a slave girl?’

Другие электронные книги автора Geoff Ryman

Lust

0

0