По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

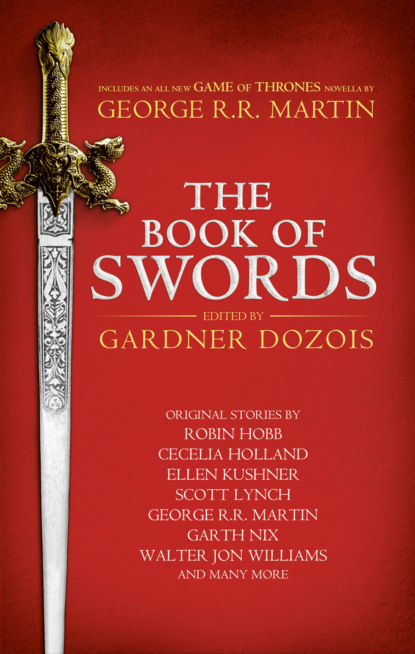

The Book of Swords

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“And have we returned there?”

The reply was grudging. “No.”

“Then obey me.”

“But—”

“Tell me,” Baldemar said. “Is Thelerion such a wizard as to encourage his underlings to second-guess his wishes? To embroider upon them their own whims and fancies?”

A shiver shook the small shoulders. “He is not such.”

“Then take us south, at more speed.”

“Still—”

“And do not speak to me again until I require it.”

The stars above rearranged their positions as the platform turned south. Its velocity increased until the wind of their passage drew tears from Baldemar’s eyes. But it was not just the chill of the upper air that made him shiver.

Soon they had left the city of Vanderoy—home to Baldemar since he had arrived as a young man to be taken on as a junior henchman to Thelerion the Exemplary—far behind. Now the platform flew south over the forest of Ilixtrey until the grand old trees gave way to heathered downs where the villages were few and the sheep many. Soon the rolling land climbed to where it abruptly fell away. Baldemar looked back and saw the alabaster cliffs of Drorn gleaming in the starlight and knew that he was over the Sundering Sea, its faint salty reek tainting the wind that blustered against his face.

He calculated as best he could their speed, the distance to the sea’s farther shore, and the time remaining before Thelerion would begin to wonder why the platform was not landing on the terrace of his mountainside-hugging manse, with his henchman stepping down to hand him the prize he had been sent to bring.

Baldemar had no doubt that the thaumaturge would be able to reach out to his imps, and the moment he did so the platform would reverse course and leave him with the choice between returning to Thelerion’s wrath—legendary for its depth and inventive display—or leaping to a quick, cold death in the gray waters far below.

But no, he thought, the imps would bring the platform down beneath me faster than I could fall. They would catch me then they would make sure I did not try again.

He voiced a short word that was out of context yet appropriate to the gravity of his situation, folded his arms across his chest, and shivered. His agile mind began rapidly considering plans, but just as quickly discarding them. Evading vengeful wizards was a complex task, even for a man with ten working fingers and both his boots.

The dark sky was paler off to his left. Baldemar limped to the portside rail and cupped a hand against the side of his face to shelter his eyes from the wind. The faint light became less pallid, and now he could see a line of gray that gradually resolved into an overcast that stretched from every horizon to every other. Ahead, the cloud layer became darker and soon he was flying through a cold rain.

He leaned against the balustrade and looked down. Darkness still ruled the world below but after a few more shivers he saw that the sea was no longer beneath him. He was flying above another forest, this one of dark conifers stretching unbroken as far as he could see, except far off to his right, dim in the distance, where he saw cleared land, and beyond, on the slopes of an eminence, a conglomeration of buildings of various sizes surrounded by a wall, with towers set in it at intervals. Atop the heights sat a more imposing structure of gray stone, with its own crenellated walls and a tall keep from which flew a gold-and-black banner.

He began to look around for a clearing to land in. He would send the platform on its way farther south and hope that some southern thaumaturge might seize it for his own. But even as he spotted a distant opening in the forest, the floor beneath him tilted as the platform heeled over and began to head for the castle.

He shouted for the imps’ attention. “Not that way!” he said. “Over there!” he added, pointing.

But the red imp poked its head up through the balustrade, and said, “We are summoned thence.”

“Can you not resist the summons?” Baldemar said.

The creature gave an equivocal toss of its head. “Perhaps. But we really don’t care to.”

The platform pursued a slanted course over the town then spiraled down toward a flat-roofed round tower on the castle. A lean old man in a figured robe stood there, his mouth pursed in concentration and a short length of black wood loose in one veined hand. The imps set the vehicle down softly, as if eager to demonstrate their capabilities, then both scuttled out from under to bob and bow in front of the wizard. Baldemar remained seated in the platform’s chair, his posture and face indicative of one who expects an explanation for rude and boisterous behavior.

But the man in the robe addressed himself first to the imps. “Explain yourselves.”

This the red one did, with much more prostrating and head-nodding, declaring that they were indentured to Thelerion the Exemplary, Grand Thaumaturge of the Thirty-Third Degree, while the spotted one mimicked every movement to support what was being said.

“And that one,” the wizard asked, gesturing with the wand toward Baldemar. “What of him?”

“Don’t answer that!” Baldemar said, leaping to his feet. “I will speak for myself.”

But the interrogator made a motion with the wand and the red imp burst out with, “Oh, he’s a terrible man, and a willful liar! Trust not a word he utters!”

“Hmm,” said the wizard. He pointed the black wood at Baldemar and said a few syllables audible only to himself. The man felt a cold shiver enter through the sole of his right foot, swiftly climb his leg, torso, and neck, then exit his left ear after performing what felt like a scouring of his skull with icy water. One hand trembled uncontrollably and he had difficulty suppressing an intense urge to urinate.

“Now,” said the man with the wand, “what’s this all about?”

Baldemar had been preparing a tale of misadventure and surprise, in which he featured as a creature of purest innocence. But when he opened his mouth to speak, his tongue rebelled, and he heard himself giving an unadorned version of how his employer, Thelerion the Exemplary, had sent him to recover the Sword of Destiny, in which endeavor he had failed. “Dreading my master’s wrath, I fled across the sea on this, his flying platform,” he finished.

The wizard tugged at his nose, causing Baldemar to fear that another spell would be launched his way. Instead, he was told to accompany the wand-wielder down to his workroom. The imps were told to remain where they were. “I’ll send you up some hymetic syrup,” said the wizard.

“Ooh!” said the red imp, as the two looked at each other with widened eyes.

“Yum!” said the spotted one.

The wizard’s workroom was depressingly familiar. Thelerion’s had much the same contents: shelves crammed with ancient tomes, mostly leather-bound, some of the hides scaly; glass and metal vessels on a workbench, one of them steaming though no fire was set beneath it; an oval looking glass hanging on one wall, its surface reflecting nothing that was in this chamber; a small cage suspended on a chain in one corner, containing something that rustled when it moved.

The wizard gestured for Baldemar to sit on a stool while he went to pick through a shelf of close-packed books. “Don’t try to run away,” he said, over his shoulder. “I’ve been having trouble with my paralysis spell. The fluxions have altered polarity and the last time I used it …”—he looked up at a large stain on the ceiling—“well, let’s just say it was an awful mess to clean up.”

Baldemar sat on the stool.

The wizard sorted through the next shelf down, made a small noise of discovery, and pulled out a heavy volume bound in tattered black hide. He placed it on a chest-high lectern and began to leaf through the parchment pages. “The Sword of Destiny, you said?”

“Yes,” said Baldemar.

The thaumaturge continued to hunt through the book. “Why did he want it, this Fellow-me-whatsit of yours?”

“Thelerion,” said Baldemar, “the Exemplary. It was to complete a set of weapons and armor.” He named the other items in the ensemble: the Shield Impenetrable; the Helm of Sagacity; the Breastplate of Fortitude; the Greaves of Indefatigability. As he spoke, the wizard found a page, ran a finger down it, and his face expressed surprise.

“He was going to put these all together?”

“Yes.”

“To what purpose?”

“I don’t know.”

The long face turned toward him. “Speculate.”

“Revenge?” said Baldemar.

“He has enemies, this Folderol?”

“Thelerion. He is a thaumaturge. Do they not attract enemies as a lodestone attracts nails?”

“Hmm,” said the other. He consulted the book again, and said, “But these items do not … care for each other. They would not gladly cooperate.”