По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

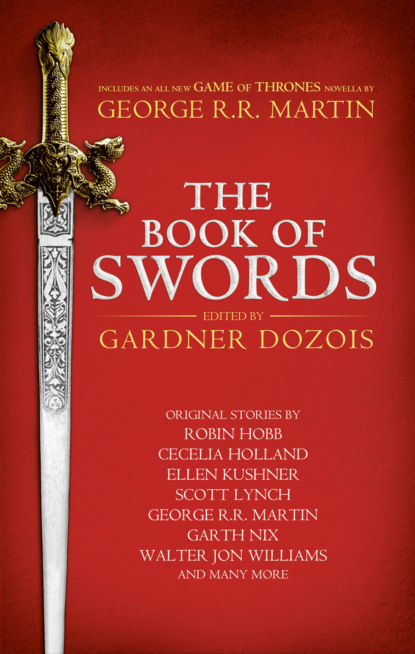

The Book of Swords

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He tugged a thoughtful nose and continued in a musing tone, “The helmet and the shield might tolerate each other, I suppose, but the greaves would pay no attention to any strategy those two agreed upon. And the sword …”

The wizard made a sound of suppressed mirth. “Tell me,” he said, “your master, he is a practitioner of which school?”

“The green school,” Baldemar said.

The wizard closed the book with a clap and a puff of dust. “Well, there you go,” he said, after a discreet sneeze. “Green school. And a norther- ner, at that. Say no more.” He shook his head and made a noise that put Baldemar in mind of an elderly spinster contemplating the lusts of the young.

The wizard put the book back where he’d found it and favored his visitor with a speculative assessment. “But you’re an interesting specimen. So, what to do with you?”

He was stroking his long chin while the series of expressions on his other features suggested that he was evaluating options without coming to a conclusion, when another man appeared in the doorway, clad in black-and-gold garments of excellent quality. He was even leaner than the wizard, his face an intricate tracery of fine wrinkles spread over a noble brow, an aristocratically arched blade of a nose, a well-trimmed beard as white as the wings of hair that swept back from his temples. A pair of gray eyes as cold as an ancient winter surveyed Baldemar as the man said, “Is he anything to do with that contraption on the roof?”

“Yes, your grace,” said the wizard. “He arrived in it.”

The aristocrat’s brows coalesced in disbelief. “He’s a thaumaturge?”

“No, your grace. A wizard’s henchman who stole his master’s conveyance.”

The man in the doorway frowned in disapproval and Baldemar shuddered. The fellow had the aspect of one who enjoyed showing thieves the error of their ways. Indeed, he looked the type to invent new and complex forms of education, the kind from which the only escape is a welcome graduation into death.

But then the frown disappeared, to be replaced by the look of a man who has just come upon an unsought but useful item. “Stole from a thaumaturge, you say? That’s an accomplishment, isn’t it?”

The wizard did not share the aristocrat’s opinion. “His master is some northern hedge-sorcerer. Green school, for Marl’s sake.”

But the man in the doorway was yielding no ground. “Say as you will, it’s an accomplishment!”

Understanding dawned in the thaumaturge’s face. “Ah,” he said, “I see where your grace is going.”

“Exactly. We could cancel the race.”

“Indeed.” The thaumaturge now again wore the face of a man who mentally balances abstract issues. After a while he said, “There is great disaffection this time around. The townspeople and the farmers have lost confidence in your … story.” He gestured toward the looking glass. “I have heard grumblings in many quarters.”

The aristocrat’s stark face became even starker. “Revolt?” he said.

A wave of a wizardly hand. “Some vague mutterings in that vein. But more are talking about packing up and moving to another county. The Duke of Fosse-Bellesay is founding new towns and clearing forest.”

The aristocrat grimaced. “Little snot-nose,” he said.

“Actually, your grace, he is now in his fifties.”

The other man waved away the implication. “I remember his great-great-grandfather. He was just the same. Tried to steal my lead soldiers.”

“Yes, your grace.”

The conversation, Baldemar saw, had meandered off and left both participants temporarily stranded. Then the aristocrat seemed to recollect himself. He rubbed his hands against each other, their skin so dry it was like hearing two sheets of parchment frictioned together, and said, “So that’s settled. He’s accomplished. He’ll do.”

The wizard considered for but a moment, then said, “I’ll need him for a little while first. I think I can get an interesting paper out of him for The Journal of Hermetic Studies. But yes, he’ll do.”

“Do for what?” Baldemar said.

But the aristocrat had already gone, and the thaumaturge was looking for another book, humming to himself as he ran a finger over their spines. Baldemar thought about easing out the door, then glanced again at the stain on the ceiling, and decided to stay.

Over the ensuing few days, Baldemar learned several things: he had landed in the County of Caprasecca, which was ruled by Duke Albero, he of the papery skin. The wizard was Aumbraj, a practitioner of the blue school. The race the Duke had mentioned was a contest held every seven years to discover a “man of accomplishment” who would be sent as an emissary of the Duke to some hazily referenced realm. He would be accompanied by a woman who had bested all others in a test of domestic skills.

“My companion is a beautiful woman?” he asked, when this news was given him by the Duke’s majordomo, a man who wore a large panache in his high-crowned black hat and was given to sniffing in disapproval at virtually everything that existence contrived to offer him.

“Comeliness is not a factor,” the functionary said, with a mocking smile. “Certainly not in this case.”

Baldemar’s hopes faded. He had briefly liked the idea of becoming an ambassador accompanied by some long-necked, pale aristocratic beauty, until the majordomo described the women’s champion as a lumbering rural wench who had been a bondsmaid on a dairy farm. “The things that were stuck to her boots defy description,” the servant said, adding a sniff of double strength.

Aumbraj had repaired Baldemar’s injuries and given him new clothing and boots. He was a prisoner but could wander the castle’s confines at will though if he saw Duke Albero at a distance, he should immediately endeavor to make that distance even greater. “But don’t try to leave,” said the thaumaturge. “You have opened up an interesting avenue of research, and I will want to question you further. That may not be possible if I have to restrain you with the paralysis spell.”

They both glanced at the workroom ceiling and agreed that Baldemar would not venture beyond the castle’s walls. However, he did stand on the battlements facing the town and saw the Duke’s men-at-arms disassembling a succession of barriers and obstacles strewn along a taped course that followed the curve of the curtain wall. There were narrow beams over mud pits, netting that must be crawled under, some barrels that had to be foot-rolled up a gentle incline, and a series of rotating drums from which protruded stout wooden bars at ankle, chest, and head height, plus some clear patches of turf for sprinting.

“It is some sort of obstacle course?” he asked a sentry.

“Yes, you could call it that,” said the guard. “The townies and bumpkins don’t like it, though. We have to wield whips to keep them running.”

“And the winner becomes the Duke’s ambassador?”

The man-at-arms regarded Baldemar as if his question had revealed him to be a simpleton. “Sure,” he said, after a moment, “his grace’s ambassador.”

Baldemar would have pressed him for a proper explanation, but at that moment he was summoned by Aumbraj. Since the summons consisted of a loud clanging in his head that only lessened when he went in the direction of the summoner and did not cease until he found him, Baldemar did not linger.

“Describe the Sword of Destiny,” the thaumaturge said when he arrived breathless in his workroom.

Baldemar did so, mentioning the ornate basket hilt and its inset jewels.

“And you just seized it?”

“Yes.”

“Show me your hand.” When the man did so, the wizard examined his palm and the inside flesh of his fingers. “No burns,” he said, apparently to himself.

Aumbraj tugged his nose again, then said, “You said you tricked the guardian erbs into entering another room then locked them in.”

“I did.”

“But once you had the Sword, they appeared and gave chase.”

“Yes.” The how of that had puzzled Baldemar. The lock had been securely set.

“And yet, they did not catch you.”

“I ran very quickly.”

“But they were erbs,” said Aumbraj. “Were they decrepit?”

“No, it was a mature dam and her two grown pups.”