По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

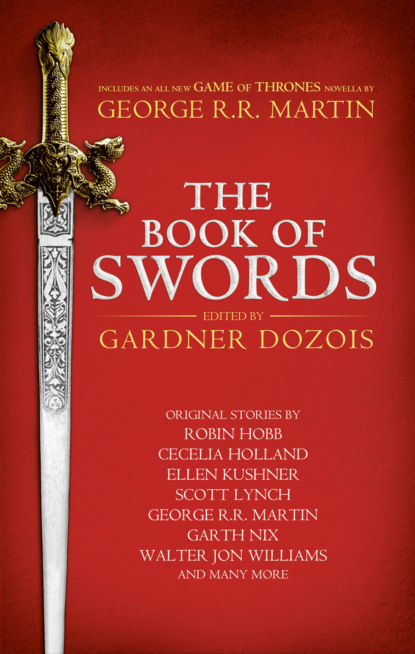

The Book of Swords

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Baldemar was mentally cudgeling his brain. What would a demon have in its hand? What would this particular demon have in its particular hand? For some reason, or no reason at all, he wanted to blurt out, A piece of cake!

The young woman began to blub, her tears and nasal flows wetting his shirt. “It’s not fair,” she said. “It doesn’t even have a hand!”

A sensation came upon Baldemar, like a cooling flow of water on a searing summer day. “Nothing,” he told the demon. “You have nothing in your hand because you don’t have a hand. Just a kind of paw, and a crabby claw thing, and …”—he couldn’t find the words—“and whatever that other thing is, but I know it’s not a hand!”

There was a silence at the bottom of the well, broken only by the woman’s stifled sobs. Then the yellow glow around the demon deepened to gold and became tinged with red around the edges. “Good-bye,” it said then swept up the shaft of the well at great speed, taking most of its stench with it.

Baldemar looked up and saw the timber lid fly apart into splinters. He pulled Enolia into the tunnel as a rain of sharp wood briefly fell, then said, “Come on!”

He threw himself at the ladder and climbed with as much alacrity as his still-trembling legs could deliver. The young woman matched him step for step. When they climbed over the rim of the well, it was early evening. He saw the flying platform, far off in the distance, framed against the dying light.

From the castle came shouts and screams, the clatter of boots on stone flags. In the nearby stables, hooves were pounding against stalls. Then, from on high, came one great cry of despair.

“Get back!” he warned the woman as a pulsing sphere of red light appeared at the top of the keep, leapt into the air, and arrowed down toward the well. It paused above the opening and Baldemar had a glimpse of the Duke wrapped in what might have been a tentacle bedecked with curved thorns, the circles of his eyes and mouth forming a perfect isosceles triangle. He was making sounds that were not quite words.

The demon had all of its eyes trained on the new addition to its collection but it let one stray toward the man. “He who made me ordained that gratitude may never be part of my nature,” it said, “but I am required to seek equipoise.”

Baldemar said, “I am not prepared to make a bargain with you. No offense meant.”

“None taken,” said the demon. “But I cannot be obligated and I find that I am, to both of you. You may each ask a service of me at no further charge.”

Baldemar took this statement and turned it over to examine it from several angles, demons being what they were. But the woman said, “I would like a nice farm, with good crop fields and healthy livestock, a warm well-furnished house with a pump right in the kitchen.”

“Done,” said the fiend. “It used to belong to the Kazakian family.”

“I was their servant,” she said. “They were always cruel to me, said I was not good enough to clean their muddy boots. The girls pulled my hair and the boys clutched me in private places.”

“I know,” said the fiend, then as an aside to Baldemar it added, “Equipoise, as I said.”

To Enolia, it said, “The Kazakians are now your indentured servants.” A claw handed her several scrolls and a cane fashioned from black, spiraled wood. “Here are all the necessary documents, and a stout stick to beat them with.”

The woman took them and clasped them to her bosom. A smile briefly softened her features before they assumed an aspect of determination. “I have to go now,” she said, and left without further ceremony.

Baldemar had finished his examination of the demon’s offer. “Free of charge?” he said. “No comebacks?”

“No comebacks, but hurry up and decide. I am eager to introduce Duke Albero to his new circumstances.”

“Can we leave it open? Can I call you when I have need?”

“If it is not too long,” said the demon. “I experience obligation as a nagging itch. When you know what you want, say the name Azzerath, and I shall arrive forthwith.” Then it disappeared down the well with the gibbering addition to its collection.

The castle was empty of people though filled with the odor the demon had left behind. Baldemar breathed through his mouth and found it bearable. He had not gone far before he came upon the majordomo’s hat, the man’s head still in it. From a room dedicated to trunks and lidded baskets he took a capacious satchel. In the Duke’s quarters, he changed into richer garments then examined the coffers and cupboards, choosing items that were valuable yet sturdy—precious metals and gems, mostly—along with as much weight in gold coins as he could carry. He also filled a purse with silver bits and bronze asses for incidentals.

The coins all bore the likeness of the Duke. Baldemar studied the aquiline profile on one then turned it to see the obverse. It showed a date from a previous century and Albero’s motto in an extinct tongue: Miro, odal miro.

Baldemar thought back to his school days and found he could translate it. “Mine, all mine,” he said. He dropped the coin into the purse, put the purse in the satchel, and patted its comforting bulk. Then he smiled the exact smile as the woman had before she set off.

The black horse the Duke had ridden was in its stall, half-maddened by the smell of demon. But Baldemar was an experienced horse handler and soon calmed the beast. He saddled and bridled it with the Duke’s own gold-chased tack and affixed the satchel securely behind. He walked it out into the courtyard, still clucking and cooing to comfort it, and saw that some of the men-at-arms had abandoned their weapons when the fiend arrived. He picked up a serviceable sword, and, since he was riding, a long-shafted lance. It had a black-and-gold pennant that he tore off.

The animal’s iron shoes beat solid notes on the drawbridge as it carried Baldemar out of the castle. The fortification’s surrounds were empty and he suspected that he would find the town similarly deserted. Demons had that effect.

“Now,” he said to himself, “I’ll ride to the land’s edge and take passage on a ship sailing north. I’ll buy myself a house in one of the Seven Cities of the Sea and invest in the fiduciary pool. Maybe I’ll get a boat and take up fishing.”

He touched his heels to the black’s sides and the horse began to canter toward the town. Just then, a voice from above him said, “There you are!”

Baldemar looked up. The flying platform was just overhead, Aumbraj leaning on the balustrade. It settled to the turf, and the wizard said, “Come aboard. We have to go.”

The man was tempted to urge the horse to a gallop. But the thaumaturge was tapping the palm of one hand with the wand. He climbed aboard and the flying platform turned north. Past the town, he looked down and saw Enolia marching along a lane that led to a capacious stone farmhouse. She paused to roll up her sleeves then used her stick to take a few practice swipes at the weeds that grew beside the track before resuming her methodical progress toward the house. When the platform’s shadow passed over her, she did not look up.

“The thing is,” the thaumaturge said, “you really ought to be dead.”

They were flying north over the Sundering Sea at an even faster speed than Baldemar had come south. Aumbraj had fed the imps well on hymetic syrup and conjured an invisible shield to protect him and Baldemar from the shrieking wind of their passage.

The wizard’s henchman had been watching the waves ripple the surface of the sea. Now he turned to the thaumaturge. “The demon would have given me a fate worse than death,” he said. “He would have taken Enolia and me for playthings.”

“I’m not talking about the demon. I’m talking about the Sword of Destiny. It is known to be very—touchy about being touched.”

He grinned at his play on words but Baldemar bored in on the substance of his remark. “You’re saying the Sword … has a will of its own?”

“A will—and a history of seeing that will turned into ways. And means, if you get what I’m saying.”

Baldemar said, “So Thelerion was sending me to be killed?” His disaffection for his employer plumbed new depths.

“I doubt that,” said Aumbraj. “He simply didn’t know what he was getting into—or, more properly, getting you into. But it’s clear from my researches that the moment your hand touched the Sword, you should have found yourself looking at a charred stump somewhere between your wrist and elbow.”

Baldemar shuddered. But the thaumaturge went on, oblivious to his distress. “Instead, the Sword merely freed the erbs you had sequestered so that they could chase you away. Even then, it did not allow them to catch you, as they certainly should have. The man has not yet been born who can outrun an erb, especially up stairs.”

Baldemar forced from his mind the image of what would have happened if the beasts had caught him.

“Then, instead of hacking off a leg, it hampered you just enough to make you leave it behind.”

“So it didn’t want to kill me, yet it didn’t want me to take it away.”

Aumbraj thoughtfully tugged his nose, then pointed a conclusive finger at Baldemar. “It did not want you to take it to this Fallowbrain who sent you,” he said, “but I think we have to deduce that it didn’t mind your touch.”

Baldemar turned back to the sea. “I am confused,” he said.

“As you ought to be. You’re probably not used to thinking of yourself as a man of destiny.”

“Indeed, I am not.”

“Well, you’d better get used to it. Once it makes up its mind, the Sword can be quite adamant.”

Aumbraj went on to describe the Sword’s history and attributes. Forged on some other Plane of existence, its exact circumstances of origin were now completely forgotten. On the Plane where it was created, it probably had some other shape and function altogether. But here on the Third Plane, it presented as an invincible weapon. Yet it was more than that. It had the inclination sometimes to single out “persons of interest”—that was the Sword’s own term—and assist them to become grand figures of the age.

“Its own term?” Baldemar said. “It speaks?”

“When it cares to,” said the wizard. “But to continue, persons possessed of overweening ambition will seek out the Sword and grasp its hilt. Most of them meet with a swift and decisive end of all their dreams. It is not a forgiving entity and hates to be harassed. But, occasionally, it picks out some seeming nonentity and raises him to heights of glory. Some have taken that as a sign the Sword possesses a sense of humor.”