По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

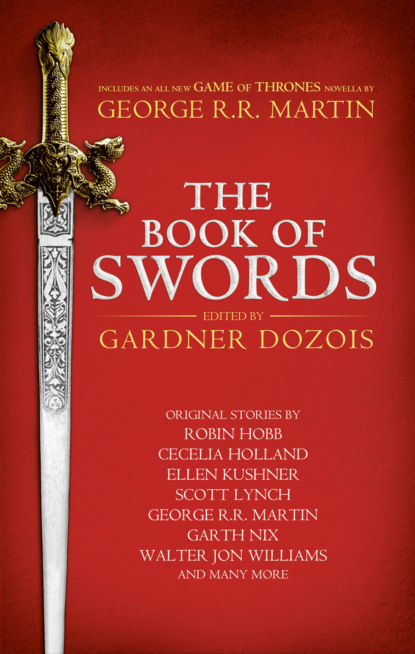

The Book of Swords

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Hmm.” The wizard made a note on a piece of parchment before him on the workbench. “You ran onto the roof and there you left the Sword behind.”

“It was hampering me, poking me in the leg.”

“Just poking? Not slashing, gouging, stabbing?”

“It was still in its scabbard, just stuck through my belt,” Baldemar said. “No one was wielding it.”

Aumbraj’s pale hand batted away his last remark as irrelevant. “Now, this Flapdoodle who sent you after it, did he equip you with any thaumaturgical aids?”

“Only the flying platform. I used my own rope and grapnel, my own lock picks.”

“Hmm, and you’re quite sure that the Sword did not seek to kill you?”

Baldemar showed surprise. “Quite sure.”

“Hmm.”

Another note on the parchment. The wizard rubbed a reflective chin then raised a finger to launch another question. But at that moment, Duke Albero appeared in the doorway, his face congested with concern. “He needs to go,” he said, flicking a finger in Baldemar’s direction.

“I may be on the verge of a significant discovery,” Aumbraj said. “This man may be more … accomplished than the usual candidate. I need another day, at least.”

The Duke’s expression brooked no argument. He consulted a timepiece he drew from his garments. “The seven years end this very afternoon. There can be no extensions.”

“But—” the wizard began.

“No buts.” The Duke was adamant. “No just-untils, or a-moment-mores. If he does not go, You-know-who will arrive. So he goes, and he goes now.”

He stepped aside and the majordomo, accompanied by two men-at-arms, entered the workroom. Baldemar found himself once more under restraint.

The Duke gestured for them to take him away but blocked the doorway long enough to tell Aumbraj, “And you will do nothing to interfere with his fulfillment of the requirements.”

The thaumaturge looked as if he might have argued but dipped his head, and said, “I will do nothing to hinder him.”

“Good.” Albero once more consulted his timepiece then said to his majordomo, “You have the medal?”

“Yes, your grace.”

“Then let’s go.”

Baldemar was taken to the castle’s forecourt, just past the gatehouse. There he stood, his attendants keeping hold of him while the majordomo took from a pouch at his belt a bronze medallion on a chain. Stamped into the metal were the words: For Merit. He showed it to the Duke, who stood in the doorway of the tower from which they had come and moved a hand in a gesture that urged speed.

The functionary hung the chain around Baldemar’s neck. Meanwhile another pair of guards emerged from a timber outbuilding leading a plump young woman in a nondescript gown whose life experiences to this point had developed in her the habits of smiling nervously and wringing her hands. She wore an identical medal.

No introductions were made. Instead the majordomo cocked his head toward a waist-high circle of masonry some distance across the courtyard, and said, “Here we go.”

“What happens next?” Baldemar said, but no one thought the question worth answering. The stone circle had the look of a well, and when he arrived at it, he peered over and saw a deep shaft descending into darkness. The young woman also took a look into the depths and her smiling and hand-wringing intensified.

“In you go,” said the man in the hat.

“What?” Baldemar adopted an explanatory tone. “I am to be an ambassador. Where is the coach to carry me, my sash of office?”

He looked about him, but saw only the woman, the guards and majordomo, the Duke, who was agitatedly gesturing, and high in the tower, at the workroom’s window, Aumbraj pointing his black wand in their direction and speaking a few syllables. The young woman gave a little start, as if someone had pinched her behind, but then the functionary was pointing toward the dark depths.

“You and she go down,” he said. “As you see, we have provided the convenience of a ladder. Or we can offer you a more rapid descent.”

The woman tried to withdraw but the guards were practiced at their task. In a moment, her arm was pinned back and she was forced to the brink of the well. “All right,” she said, “I’ll climb down.”

The functionary considerately helped her over the rim and saw her firmly onto the iron ladder. When she had descended a few rungs, Baldemar accepted the inevitable and took his place above her. Steadily they made their way down into darkness while the circle of sky overhead relentlessly shrank. Then it disappeared altogether as the guards slid a wooden cover over the well. Baldemar heard a clank of iron against stone as it was locked into place.

He had expected water, but when they came to the foot of the ladder, they were standing on dry rock. It was too dark to see anything, but a cold wind was blowing from somewhere.

He said to the woman, “What happens now?”

He could not see but could imagine her nervous smile and busy hands. “I don’t know,” she said. “They said it would be a journey to the land of Tyr-na-Nog and we would be received by princes and princesses. But …” She let her voice trail off.

“Tyr-na-Nog?” Nothing more was forthcoming so Baldemar pressed her. “Has anyone ever come back from this paradise?”

“No. But then, who would want to?”

Baldemar realized he wasn’t dealing with the realm’s most intelligent specimen of womanhood. “Did you have to run an obstacle race?” he said.

“No, that’s just for the boys. We have our own competition of women’s skills: sewing, milking a cow, baking bread, plucking a chicken.”

“And you won?”

“I was surprised,” she said. “There were better seamstresses and bakers in the contest, yet somehow they all faltered and it was I who received the accolade!”

“Which is at the bottom of a dry well.”

She said nothing, but he could hear the faint sound of her hands comforting each other.

“Stay here,” Baldemar said, “I’ll explore a little.” He felt his way around the wall until he found a gap, then he got down on hands and knees to cross it until the wall resumed again. While he crawled, he was chilled by a river of cold air. He stood up, and said, “Say something.”

“What?” Her voice came from the darkness; he oriented himself and found his way back to her side.

“There’s a tunnel,” he said.

Her voice came quavering. “Where does it go?”

He told her he did not know and had no desire to find out. They stood in the darkness and felt the wind. The flow of air must mean that the tunnel connected with the outside world, but he had no desire to grope his way through blackness in which anything might lurk.

Time passed. The woman introduced herself as Enolia. Baldemar gave her his name. They sat on the rock, backs against the wall on either side of the ladder. After a time, Baldemar let his mind wander and found himself thinking about the wizard’s questions about the Sword of Destiny. Enolia’s voice brought him back to the here and now.

“I smell something.”

His head came up and now he caught it, too: a sour odor, almost sulfurous, with a nose-tickling peppery overtone that made him want to sneeze. “It’s coming from the tunnel,” he said. A moment later, he added, “And there’s a light.”

They stood up, backs against the wall. Baldemar missed his knife, which was still in his boot, far away to the north. Then he found himself missing the Sword.