По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

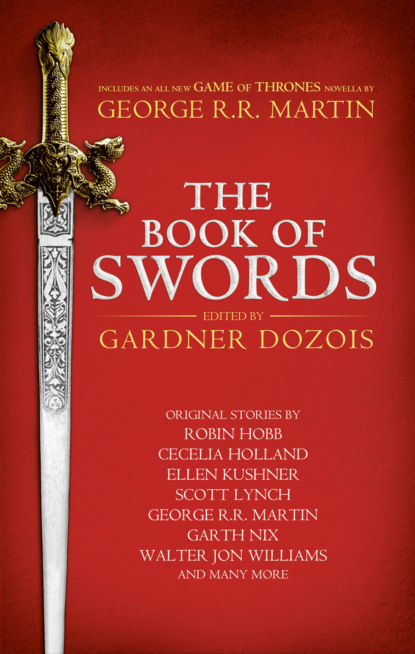

The Book of Swords

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

For a moment I suffer the illusion that I’m back in the great pagoda tree in front of my house, looking through a hole in the swaying leaves at my father.

But the moment passes. I’m going to dive through like a cormorant, slit his throat, strip off his clothes, and sprinkle corpse-dissolving powder all over his skin. Then, as he lies there on the stone floor, still twitching, I will take flight back to the ceiling and make my escape. By the time servants discover the remains of his body, barely more than a skeleton, I will be long gone. Teacher will declare my apprenticeship to be at an end, myself an equal of my sisters.

I take a deep breath. My body is coiled. I’ve trained and practiced for this moment for six years. I’m ready.

“Baba!”

I hold still.

The boy who emerges from behind the curtains is about six years old, his hair tied into a neat little braid that points straight up like the tail of a rooster.

“What are you doing still up?” the man asks. “Be a good boy and go back to sleep.”

“I can’t sleep,” the boy says. “I heard a noise, and I saw a shadow moving on the courtyard wall.”

“Just a cat,” the man says. The boy looks unconvinced. The man looks thoughtful for a moment, then says, “All right, come over.”

He sets the papers aside on the low desk next to him. The boy scrambles into his lap.

“Shadows are nothing to be afraid of,” he says. Then he proceeds to make a series of shadow puppets with his hands held against the reading light. He teaches the boy how to make a butterfly, a puppy, a bat, a sinuous dragon. The boy laughs in delight. Then the boy makes a kitten to chase his father’s butterfly across the papered windows of the large hall.

“Shadows are given life by light, and they also die by light.” The man stops fluttering his fingers and lets his hands fall by his side. “Go to sleep, child. In the morning you can chase real butterflies in the garden.”

The boy, heavy-eyed, nods and leaves quietly.

On the roof, I hesitate. The boy’s laughter will not leave my mind. Can the girl stolen from her family steal family away from another child? Is this the moral pronouncement of a hypocrite?

“Thank you for waiting until my son has left,” the man says.

I freeze. There’s no one in the hall but him, and he’s too loud to be talking to himself.

“I prefer not to shout,” he says, his eyes still on the bundle of papers. “It would be easier if you came down.”

The pounding of my heart is a roar in my ears. I should flee immediately. This is probably a trap. If I go down, he might have soldiers in ambush or some mechanism under the floor of the hall to capture me. Yet, something in his voice compels me to obey.

I drop through the hole in the roof, the silk cord attached to the grappling hook looped about my waist a few times to slow my descent. I land gently before the dais, silent as a snowflake.

“How did you know?” I ask. The bricks at my feet have not flipped open to reveal a yawning pit and no soldiers have rushed from behind the screens. But my hands grip the cord tightly and my knees are ready to snap. I can still complete my mission if he truly is defenseless.

“Children have sharper ears than their parents,” he says. “And I have long made shadow puppets for my own amusement while reading late at night. I know how much the lights in this hall usually flicker without the draft from a new opening in the ceiling.”

I nod. It’s a good lesson for the next time. My right hand moves to grasp the handle of the dagger in the sheath at the small of my back.

“Jiedushi Lu of Chenxu is ambitious,” he says. “He has coveted my territory for a long time, thinking of pressing the young men in its rich fields into his army. If you strike me down, there will be no one to stand between him and the throne in Chang’an. Millions will die as his rebellion sweeps across the empire. Hundreds of thousands of children will become orphans. Ghostly multitudes will wander the land, their souls unable to rest as beasts pick through their corpses.”

The numbers he speaks of are vast, like the countless grains of sand suspended in the turbid waters of the Yellow River. I can’t make any sense of them. “He saved my teacher’s life once,” I say.

“And so you will do as she asks, blind to all other concerns?”

“The world is rotten through,” I say. “I have my duty.”

“I cannot say that my hands are free of blood. Perhaps this is what comes of making compromises.” He sighs. “Will you at least allow me two days to put my affairs in order? My wife departed this world when my son was born, and I have to arrange for his care.”

I stare at him. I can’t treat the boy’s laughter as an illusion.

I picture the governor surrounding his house with thousands of soldiers; I picture him hiding in the cellar, trembling like a leaf in autumn; I picture him on the road away from this city, whipping his horse again and again, grimacing like a desperate marionette.

As if reading my mind, he says, “I will be here, alone, in two nights. I give you my word.”

“What is the word of a man about to die worth?” I counter.

“As much as the word of an assassin,” he says.

I nod and leap up. Scrambling up the dangling rope as swiftly as I ascend one of the vines on the cliff at home, I disappear through the hole in the roof.

I’m not worried about the jiedushi’s escaping. I’ve been trained well, and I will catch him no matter where he runs. I’d rather give him the chance to spend some time saying good-bye to his little boy; it seems right.

I wander the markets of the city, soaking up the smell of fried dough and caramelized sugar. My stomach growls at the memory of foods I have not had in six years. Eating peaches and drinking dew may have purified my spirit, but the flesh still yearns for earthly sweetness.

I speak to the vendors in the language of the court, and at least some of them have a passing mastery of it.

“That is very skillfully made,” I say, looking at a sugar-dough general on a stick. The figurine is wearing a bright red war cape glazed with jujube juice. My mouth waters.

“Would you like to have it?” the vendor asks. “It’s very fresh, young mistress. I made it only this morning. The filling is lotus paste.”

“I don’t have any money,” I say regretfully. Teacher gave me only enough money for lodging, and a dried peach for food.

The vendor considers me and seems to make up his mind. “By your accent I take it you’re not a local?”

I nod.

“Away from home to find a pool of tranquility in this chaotic world?”

“Something like that,” I say.

He nods, as if this explains everything. He hands the stick of the sugar-dough general to me. “From one wanderer to another, then. This is a good place to settle.”

I accept the gift and thank him. “Where are you from?”

“Chenxu. I abandoned my fields and ran away when the Jiedushi Lu’s men came to my village to draft boys and men for the army. I had already lost my father, and I wasn’t interested in dying to add color to his war cape. That figurine is modeled after Jiedushi Lu. It gives me pleasure to watch patrons bite his head off.”

I laugh and oblige him. The sugar dough melts on the tongue, and the succulent lotus paste that oozes out is delightful.

I walk about the alleyways and streets of the city, savoring every bite of the sugar-dough figurine as I listen to snatches of conversation wafting from the doors of teahouses and passing carriages.

“… why should we send her across the city to learn dance? …”

“The magistrate isn’t going to look kindly on such deception …”