По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

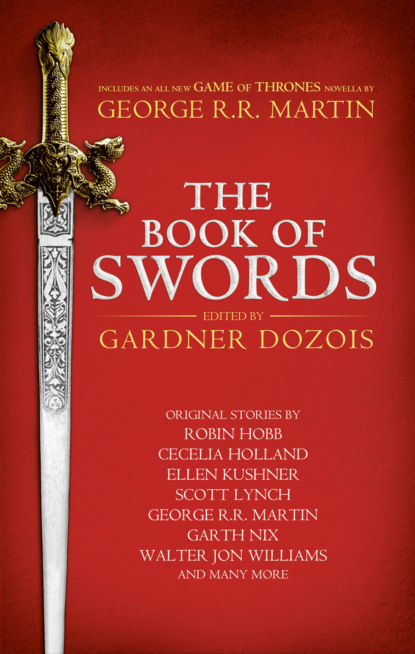

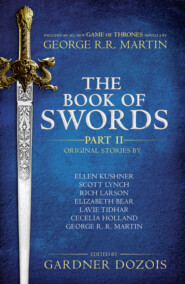

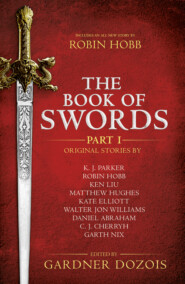

The Book of Swords

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Not likely.

She ran after him, the bared sword heavy and jouncing with every step she took. “Papa! Wait! You’ll need your sword!” she called after him. He glanced back at her but said nothing as he halted. But he waited for her. When she caught up with him, he walked on.

She followed him into the darkness.

Ken Liu

Ken Liu is an author and translator of speculative fiction, as well as a lawyer and programmer. His fiction has appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Asimov’s Science Fiction, Analog, Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, and Strange Horizons, among many other places. He has won a Nebula, two Hugos, a World Fantasy Award, and a Science Fiction & Fantasy Translation Award, and been nominated for the Sturgeon and the Locus awards. In 2015, he published his first novel, The Grace of Kings. His most recent books are The Wall of Storms, a sequel to The Grace of Kings, a collection, The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories, and, as editor and translator, an anthology of Chinese science-fiction stories, Invisible Planets. He lives with his family near Boston, Massachusetts.

Here a young girl pressed into service as an assassin faces one final test of her skills—if she lives through it.

THE HIDDEN GIRL (#ulink_c6aed7a9-fbc5-5d28-adfe-5fdc79c865c2)

Beginning in the eighth century, the Imperial court of Tang Dynasty China increasingly relied on military governors—the jiedushi—whose responsibilities began with border defense but gradually encompassed taxation, civil administration, and other aspects of political power. They were, in fact, independent feudal warlords whose accountability to Imperial authority was nominal.

Rivalry among the governors was often violent and bloody.

On the morning after my tenth birthday, spring sunlight dapples the stone slabs of the road in front of our house through the blooming branches of the pagoda tree. I climb out onto the thick bough pointing west like an immortal’s arm and reach for a strand of yellow flowers, anticipating the sweet taste tinged with a touch of bitterness.

“Alms, young mistress?”

I look down and see a bhikkhuni. I can’t tell how old she is—her face is unlined but there is a fortitude in her dark eyes that reminds me of my grandmother. The light fuzz over her shaved head glows in the warm sun like a halo, and her grey kasaya is clean but tattered at the hem. She holds up a wooden bowl in her left hand, gazing up at me expectantly.

“Would you like some pagoda-tree flowers?” I ask.

She smiles. “I haven’t had any since I was a young girl. It would be a delight.”

“If you stand below me, I’ll drop some into your bowl,” I say, reaching for the silk pouch on my back.

She shakes her head. “I can’t eat flowers that have been touched by another hand—too infected with the mundane concerns of this dusty world.”

“Then climb up yourself,” I say. Immediately I feel ashamed at my annoyance.

“If I get them myself, they wouldn’t be alms, now would they?” There’s a hint of laughter in her voice.

“All right,” I say. Father has always taught me to be polite to the monks and nuns. We may not follow the Buddhist teachings, but it doesn’t make sense to antagonize the spirits, whether they are Daoist, Buddhist, or wild spirits who rely on no learned masters at all. “Tell me which flowers you want; I’ll try to get them for you without touch- ing them.”

She points to some flowers at the end of a slim branch below my bough. They are paler in color than the flowers from the rest of the tree, which means they are sweeter. But the branch they dangle from is much too thin for me to climb.

I hook my knees around the thick bough I’m on and lean back until I’m dangling upside down like a bat. It’s fun to see the world this way, and I don’t care that the hem of my dress is flapping around my face. Father always yells at me when he sees me like this, but he never stays angry at me for too long, on account of my losing my mother when I was just a baby.

Wrapping my hands in the loose folds of my sleeves, I try to grab for the flowers. But I’m still too far from the branch she wants, those white flowers tantalizingly just out of reach.

“If it’s too much trouble,” the nun calls out, “don’t worry about it. I don’t want you to tear your dress.”

I bite my bottom lip, determined to ignore her. By tightening and flexing the muscles in my belly and thighs, I begin to swing back and forth. When I’ve reached the apex of an upswing I judge to be high enough, I let go with my knees.

As I plunge through the leafy canopy, the flowers she wants brush by my face and I snap my teeth around a strand. My fingers grab the lower branch, which sinks under my weight and slows my momentum as my body swings back upright. For a moment, it seems as if the branch would hold, but then I hear a crisp snap and feel suddenly weightless.

I tuck my knees under me and manage to land in the shade of the pagoda tree, unharmed. Immediately, I roll out of the way, and the flower-laden branch crashes to the spot on the ground I just vacated a moment later.

I walk nonchalantly up to the nun and open my jaw to drop the strand of flowers into her alms bowl. “No dust. And you only said no hands.”

In the shade of the pagoda tree, we sit with our legs crossed in the lotus position like the Buddhas in the temple. She picks the flowers off the stem: one for her, one for me. The sweetness is lighter and less cloying than the sugar-dough figurines Father sometimes buys me.

“You have a talent,” she says. “You’d make a good thief.”

I look at her, indignant. “I’m a general’s daughter.”

“Are you?” she says. “Then you’re already a thief.”

“What are you talking about?”

“I have walked many miles,” she says. I look at her bare feet: the bottoms are calloused and leathery. “I see peasants starving in fields while the great lords plot and scheme for bigger armies. I see ministers and generals drink wine from ivory cups and conduct calligraphy with their piss on silk scrolls while orphans and widows must make one cup of rice last five days.”

“Just because we are not poor doesn’t make us thieves. My father serves his lord, the Jiedushi of Weibo, with honor and carries out his duties faithfully.”

“We’re all thieves in this world of suffering,” the nun says. “Honor and faith are not virtues, only excuses for stealing more.”

“Then you’re a thief as well,” I say, anger making my face glow with heat. “You accept alms and do no work to earn them.”

She nods. “I am indeed. The Buddha teaches us that the world is an illusion, and suffering is inevitable as long as we do not see through it. If we’re all fated to be thieves, it’s better to be a thief who adheres to a code that transcends the mundane.”

“What is your code then?”

“To disdain the moral pronouncements of hypocrites; to be true to my word; to always do what I promise, no more and no less. To hone my talent and wield it like a beacon in a darkening world.”

I laugh. “What is your talent, Mistress Thief?”

“I steal lives.”

The inside of the cabinet is dark and warm, the air redolent of camphor. By the faint light coming through the slit between the doors, I arrange the blankets around me to make a cozy nest.

The footsteps of patrolling soldiers echo through the hallway outside my bedroom. Each time one of them turns a corner, the clanging of armor and sword marks the passage of another fraction of an hour, bringing me closer to morning.

The conversation between the bhikkhuni and my father replays through my mind.

“Give her to me. I will have her as my student.”

“Much as I’m flattered by the Buddha’s kind attention, I must decline. My daughter’s place is at home, by my side.”

“You can give her to me willingly, or I can take her away without your blessing.”

“Are you threatening me with a kidnapping? Know that I’ve made my living on the tip of a sword, and my house is guarded by fifty armed men who will give their lives for their young mistress.”

“I never threaten; I simply inform. Even if you keep her in an iron chest ringed about with bronze chains at the bottom of the ocean, I will take her away as easily as I cut your beard with this dagger.”

There was a cold, bright, metallic flash. Father drew his sword, the grinding noise of blade against sheath wringing my heart so that it leaped wildly.