По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

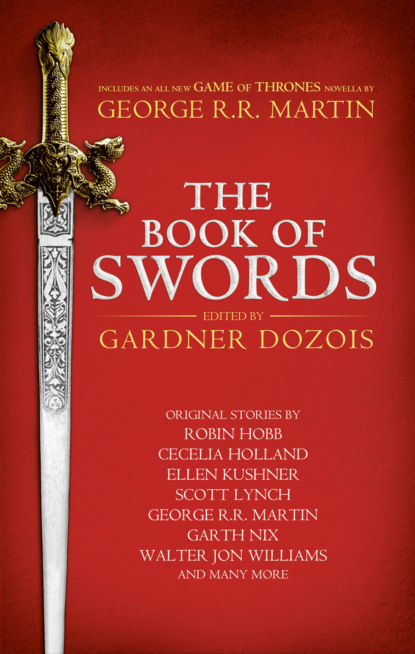

The Book of Swords

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Well?”

“My name is Aimeric de Peguilhan,” he said. “My father was Bernhart de Peguilhan. You murdered him in a brawl, in Ultramar. You smashed his skull with a stone bottle, when his back was turned.” He dropped the broom-handle. “Wait there,” he said, “I’ll fetch the swords and be right back.”

I’m telling this story, so you know what happened.

He had the best sword ever made, and I’d taught him everything I ever knew, and he ended up better than me; he was always better than me, just like his father. Nearly everybody’s better than me, in most respects. One way in which he excelled me was, he lacked the killer instinct.

But he made a pretty fight of it, I’ll give him that. I wish I could have watched that fight instead of being in it; there never was better entertainment, and all wasted, because there was nobody to see. Naturally you lose all track of time, but my best educated guess is, we fought for at least five minutes, which is an eternity, and never a hair’s breadth of difference between us. It was like fighting your own shadow, or your reflection in the mirror. I read his mind, he read mine. To continue the tedious extended metaphor, it was forge-welding at its finest. Well; I look back on it in these terms, the same way I look back on all my best completed work, with pleasure once it’s over but hating every minute of it while I’m actually doing it.

When I wake up in the middle of the night in a muck-sweat, I tell myself I won because he trod on a stone and turned his ankle, and the tiny atom of advantage was enough. But it’s not true. I’m ashamed to say I beat him fair and square, through stamina and the simple desire to win: killer instinct. I made a little window of opportunity by feigning an error. He believed me, and was deceived. It was only a tiny opportunity, no scope for choice; I had a fraction of a second when his throat was exposed and I could reach it with a scratch-cut with the point, what we call a stramazone. I cut his throat, then jumped back to keep from getting splashed all over. Then I buried him in the midden, along with the pig-bones and the household shit.

He should have won. Of course he should. He was basically a good kid, and had he lived he’d probably have been all right, more or less; no worse than my father, at any rate, and definitely a damn sight better than me. I like to tell myself, he died so quickly he never knew he’d lost.

But; on the day, I proved myself the better man, which is what sword-fighting is all about. It’s a simple, infallible test, and he failed and I passed. The best man always wins; because the definition of best is still alive at the end. Feel at liberty to disagree, but you’ll be wrong. I hate it, but it’s the only definition that makes any sense at all.

Every morning I cough up black soot and grey mud, the gift of the fire and the grindstone. Smiths don’t live long. The harder you work, the better you get, the more poisonous muck you breathe in. My pre-eminence will be the death of me, someday.

I sold his sword to the Duke of Scona for, I forget how much; it was a stupid amount of money, at any rate, but the Duke said he wanted the very best, and he got what he paid for. My barrel of gold is now nearly full, incidentally. I don’t know what I’ll do when the level reaches the top. Something idiotic, probably.

I may have all the other faults in the world, but at least I’m honest. You have to grant me that.

Robin Hobb

New York Times bestseller Robin Hobb is one of the most popular writers in fantasy today, having sold more than one million copies of her work in paperback. She’s perhaps best known for her epic fantasy Farseer series, including Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest, as well as the two fantasy series related to it, the Liveship Traders series, consisting of Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, and Ship of Destiny, and the Tawny Man series, made up of Fool’s Errand, The Golden Fool, and Fool’s Fate. She’s also the author of the Soldier Son series, composed of Shaman’s Crossing, Forest Mage, and Renegade’s Magic, and the Rain Wild Chronicles, consisting of Dragon Keeper, Dragon Haven, City of Dragons, and Blood of Dragons. Most recently she’s started a new series, the Fitz and the Fool trilogy, consisting of Fool’s Assassin, Fool’s Quest, and, in 2017, Assassin’s Fate. Hobb also writes under her real name, Megan Lindholm. Books by Megan Lindholm include the fantasy novels Wizard of the Pigeons, Harpy’s Flight, The Windsingers, The Limbreth Gate, Luck of the Wolves, The Reindeer People, Wolf’s Brother, and Cloven Hooves, the science-fiction novel Alien Earth, and, with Steven Brust, the collaborative novel The Gypsy. Lindholm’s most recent book is a “collaborative” collection with Robin Hobb, The Inheritance: And Other Stories.

In the chilling tale that follows, FitzChivalry Farseer visits a village caught up in the Red Ship Wars, where the unhappy villagers face some very hard choices, none of them good—and some of them worse than others.

HER FATHER’S SWORD (#ulink_f0472202-cf5e-5e00-b38b-fea7e6f5eb8a)

Taura shifted on her lookout’s platform. Cold was stiffening her, and calling two skinny logs tied across a couple of outreaching branches a “watchtower platform” was generous. A flat surface would have been kinder to her buttocks and back. She shifted to a squat and checked the position of the moon again. When it was over the Hummock on Last Chance Point, her watch would be over and Kerry would come to relieve her. In theory.

They’d given her the least likely point of entry to the village. Her tree overlooked the market trail that led inland, to Higround Market where they sold their fish. Unlikely that Forged would come from this direction. The kidnapped people had been forced from their homes and down to the beach. Past their burned fishing boats and the ransacked smoking racks for preserving the catch the captured townsfolk had gone. A boy who had dared to follow his kidnapped mother said the raiders had forced their folk into boats and rowed them out to a red-hulled ship anchored offshore. As they had been taken to the sea, so they would return from the waves.

Taura had seen them go from her hiding place in the big willow that overlooked the harbor. The raiders hadn’t seemed to care who they took. She’d seen old Pa Grimby, and Salal Greenoak carrying her nursing baby. She’d seen the little Bodby twins and Kelia and Rudan and Cope. And her father, roaring and staggering with blood sheeting down the side of his face. She had known the names of almost every captive. Smokerscot was not a big village. There were perhaps six hundred folk here.

Well. There had been perhaps six hundred. Before the raid.

After the raid, Taura had helped stack the bodies after they’d put out the fires. She’d stopped counting after forty, and those were just the people in the stack on the east end of the village. There’d been another pyre near the rickety dock. No. The dock wasn’t rickety anymore. It was charred pilings sticking out of the water next to the sunken hulks of the small fishing fleet. Her father’s boat was among them. The changes had all happened so fast that it was hard to remember them. Earlier tonight, she’d decided to run back home and get a warmer cloak. Then she’d recalled that her home was wet ash and charred planks. It wasn’t the only one. The five adjoining houses had burned, and dozens of others in the village. Even the Kelp’s grand house, two stories, not even finished, was now a smoking pile of timbers.

She shifted on her platform and something poked her. She’d sat on her whistle on its lanyard. The village council had given her a cudgel and a whistle to blow if she saw anyone approaching. Two blasts from her whistle would bring the strong folk from the village with their “weapons.” They would come with their poles and axes and gaff hooks. And Jelin would come, wearing her father’s sword. What if no one came to her whistle? She had a cudgel. As if she were going to climb down from the tree and try to bash someone. As if she could bear to club people she had known since she was a babe.

A rhythmic clopping reached her ears. A horse approaching? It was past sundown, and few travelers came to Smokerscot at any time, save the fish buyers who came at the end of summer to dicker for the fall run of redfish. But in winter, and after dark? Who would be coming this way? She watched the narrow stripe of hard-packed earth that led through the forested hills to Higround, peering through the darkness.

A horse and rider came into sight. A single rider and horse, bearing a lumpy bundle on the saddle before him and two bulging panniers behind him. As she stared, the bundle wriggled and gave a long whine, then burst into the full-throated fury of an angry child.

She blew a single blast on her whistle, the “maybe it’s danger” signal. The rider halted and stared toward her perch. He did not reach for a bow. Indeed, it looked to be all he could do to restrain the child that he held before him. She stood, rolled her back a bit to remove some of the chill-stiffened kinks, and began the climb down. By the time she reached the ground, Marva and Carber had appeared. And Kerry, long past his time to come and relieve her. They stood with tall poles, blocking the horse’s path. Over the sound of the child’s wailing, they were trying to question him. By their torches, she saw a young man with dark hair and eyes. His thick wool cloak was Buck blue. She wondered what was in his horse’s panniers.

He finally shouted, “Will someone take this boy from me? He says his name is Peevy and his mother’s name is Kelia! He said he lived in Smokerscot, and pointed this way. Does he belong here?”

“Kelia’s boy!” Marva exclaimed, and came closer to examine the kicking, wriggling child. “Peevy! Peevy, it’s me, Cousin Marva. Come to me, now! Come to me.”

As the man started to lower the child from his tall black mount, the small boy twisted to hit at him shouting, “I hate you! I hate you! Let me go!”

Marva stepped back suddenly. “He’s Forged, isn’t he? Oh, sweet Eda, what shall we do? He’s just four, and Kelia’s only child. The raiders must have taken him when they took her. I thought he’d died in the fires!”

“He’s not Forged,” the rider said with some impatience. “He’s angry because I had no food for him. Please. Take him.” The youngster was kicking his heels against the horse’s shoulder and varying his now-incoherent wails with shouting for his mother. Marva stepped forward. Peevy kicked her a few times before she engulfed him in her arms. “Peevy, Peevy, it’s me, you’re safe! Oh, lovey, you’re safe now. You’re so cold! Can you calm down?”

“I’m hungry!” the boy shouted. “I’m cold. Mosquitoes bit me and I cut my hands on the barnacles and Mama threw me off the boat! She threw me off the boat into the dark water and she didn’t care! I screamed and the boat left me in the water. And the waves pushed me and I had to climb up the rocks, then I was losted in the wood!” He aired all his grievances in a child’s shrill voice.

Taura edged up beside Kerry. “Your watch, now,” she reminded him.

“I know that,” he told her in disdain as he stared down at her. She shrugged. She’d reminded him. It wasn’t her task to see he did his share. She’d done hers.

The stranger dismounted. He led his horse into the village as if certain of that right. Taura marked how everyone fell in around him, forgetting to challenge him at all. Well, he wasn’t Forged. A Forged one would never have helped a child. He gave the boy in Marva’s arms a sympathetic look. “That explains a great deal.” He looked over at Carber. “The boy darted out of the forest right in front of my horse, crying and shouting for help. I’m glad he has kin still alive to take him in. And sorry that you were raided. You aren’t the only ones. Up the coast, Shrike was raided last week. That’s where I was bound.”

“And who are you?” Carber demanded suspiciously.

“King Shrewd received a bird from Shrike and dispatched me right away. My name is FitzChivalry Farseer. I was sent to help at Shrike; I didn’t know you’d been raided as well. I cannot stay long, but I can tell you what you need to know to deal with this.” He lifted his voice to address those who had trooped out to see what Taura’s whistle meant. “I can teach you how to deal with the Forged ones. As much as we know how to deal with them.” He looked around at the circle of staring faces, and said more strongly, “The king has sent me to help folk like you. Man your watch stations, but call a meeting of everyone else in the village. I need to speak to all of you. Your Forged ones may return at any time.”

“One man?” Carber asked angrily. “We send word to our king that we are raided, that folk are carried off by the Red-Ship Raiders, and he sends us one man?”

“Chivalry’s bastard,” someone said. It sounded like Hedley, but Taura couldn’t be certain in the dusk. Folk were coming out of the houses that remained standing and joining the trailing group of people following the messenger and his horse. The man ignored the slur.

“The king did not send me here but to Shrike. I’ve come out of my way to bring the boy back to you. Did the raiders leave your inn standing? I’d appreciate a meal and a place to stable my horse. Last night we were out in the rain. And the inn might be a good place for folk to gather to hear what I have to say.”

“Smokerscot never had an inn. Not much call for one. The road ends here, at the cove. Everyone who lives here sleeps in his own bed at night.” Carber sounded insulted that the king’s man could have imagined Smokerscot had an inn.

“They used to,” Taura said quietly. “Now a lot of us don’t have beds to sleep in.” Where was she going to sleep tonight? Probably at her neighbor’s house. Jelin had offered her a blanket on the floor by his fire. That was a kind thing to do, her mother had said. The neighborly thing to do. Her younger brother Gef had echoed her words exactly. And when Jelin had asked for it, they’d given him Papa’s sword. As if they owed it to him for doing a decent thing. The sword was one of the few things they had saved from their house when the raiders set it on fire. “Your brother is too young, and you will never be strong enough to swing it. Let Jelin have it.” So her mother had said and sternly shushed her when she’d discovered what they had done. “Remember what your father always said. Do what you must to survive and don’t look back.”

Taura recalled well when he’d said that. He and his crew of two had dumped most of their catch overboard so they could ride out a sudden storm. Taura thought it was quite one thing to surrender something valuable to stay alive and quite another to give away the last valuable thing they had to a swaggering braggart. Her mother might say she’d never be strong enough to swing it, but she didn’t know that Taura could already lift it. Several times when her father had taken it out of an evening to wipe it clean and oil it fresh, he’d let her hold it. It always took both her hands, but the last time, she’d been able to lift it and swing it, however awkwardly. Papa had given a gruff laugh. “The heart but not the muscle. Too bad. I could have used a tall son with your spirit.” He’d given Gef a sideways glance. “Or any sort of a son with a mind,” he’d mutter.

But she had not been a son, and instead of her father’s size and strength, she was small, like her mother. She was of an age to work the boat alongside her father, but he’d never taken her. “Not enough room on the deck for a hand who can’t pull the full weight of a deckhand’s duties. It’s too bad.” And that was the end of it. But still, later that month, he’d again let her lift the bared sword. She’d swung it twice before the weight of it had drawn the point of it down to the earth again.

And her father had smiled at her.

But now Papa was gone, taken by the Red-Ship Raiders. And she had nothing of his.

Taura was the elder; the sword should have been hers, whether she could swing it or not. But the way it had happened, she’d had no real say. She’d come back from dragging bodies to the pyre, come back to Jelin’s house to see the sword standing in its sheath in the corner, like a broom! She and her mother and Gef could sleep on the floor of Jelin’s house, and he could have the last valuable item her family owned. And her mother thought that good. How was that a fair trade? It cost him nothing for them to sleep on his floor. Clearly her mother had no idea of how to survive.

Don’t think about that.

“… the fish-smoking shed,” Carber was saying. “It’s mostly empty now. But we can start up the fires for heat instead of smoke and gather a lot of folk there.”

“That would be good,” the stranger said.

Marva smiled up at him. Peevy had stopped struggling. He had his arms around his cousin’s neck and his face buried in her cloak. “There is room in our home for you to sleep, sir. And too much room now in our goat shed for your horse.” Her smile twisted bitterly. “The raiders left us few animals to shelter. What they did not take they killed.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” he said wearily, and it seemed to Taura it was a tale he had heard before and perhaps that was what he always replied to it.