По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

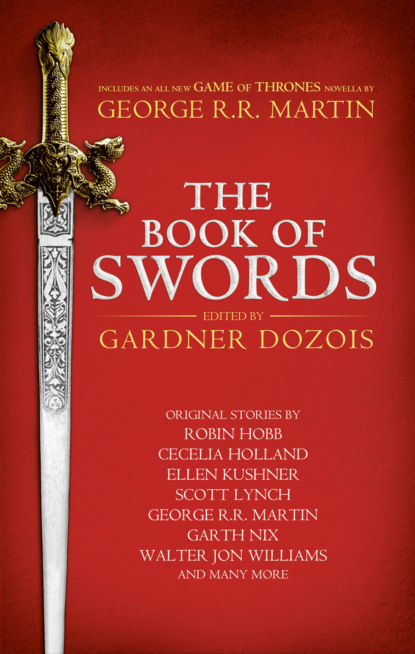

The Book of Swords

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Yes, well, it’s prime arable land. Where I come from, you could buy a whole valley.”

I sighed. “There’s bread and cheese indoors,” I said, “and a side of bacon.”

At least that got rid of him for a bit, and I closed up the fold and decided I needed a rest. I’d been staring at white-hot metal for rather too long, and I could barely see past all the pretty shining colours.

He came back with half a loaf and all my cheese. “Have some,” he said, like he owned the place.

I don’t talk with my mouth full, it’s rude, so I waited till I’d finished. “So where are you from, then?”

“Fin Mohec. Heard of it?”

“It’s a fair-sized town.”

“Ten miles north of Fin, to be exact.”

“I knew a man from Fin once.”

“In Ultramar?”

I frowned. “Who told you that?”

“Someone in the village.”

I nodded. “Nice part of the world, the Mohec valley.”

“If you’re a sheep, maybe. And we weren’t in the valley, we were up on the moor. It’s all heather and granite outcrops.”

I’ve been there. “So,” I said, “you left home to seek your fortune.”

“Hardly.” He spat something out, probably a hard bit of bacon rind. You can break your teeth on that stuff. “I’d go back like a shot if there were anything left for me there. Where were you in Ultramar, precisely?”

“Oh, all over the place,” I said. “So, if you like the Mohec so much, why did you leave?”

“To come here. To see you. To buy a sword.” A decidedly forced grin. “Why else?”

“What do you need a sword for in the Mohec hills?”

“I’m not going to use it there.”

The words had come out in a rush, like beer spilt when some fool jostles your arm in the taproom. He took a deep breath, then went on, “At least, I don’t imagine I will.”

“Really.”

He nodded. “I’m going to use it to kill the man who murdered my father, and I don’t think he lives round here.”

I got into this business by accident. That is, I got off the boat from Ultramar, and fifty yards from the dock was a forge. I had one thaler and five copper stuivers in my pocket, the clothes I’d worn under my armour for the last two years, and a sword worth twenty gold angels that I’d never sell, under any circumstances. I walked over to the forge and offered to give the smith the thaler if he taught me his trade.

“Get lost,” he said.

People don’t talk to me like that. So I spent the thaler on a third-hand anvil, a selection of unsuitable hammers, a rasp, a leg-vise and a bucket, and I lugged that damned anvil around with me—three hundredweight—until I found a half-derelict shed out back of a tannery. I offered the tanner three stuivers for rent, bought a stuiver’s worth of rusty files and two barley loaves, and taught myself the trade, with the intention of putting the other smith out of business within a year.

In the event it took me six months. I grant you, I knew a little bit more about the trade than the foregoing implies; I’d sat in the smithy at home on cold mornings and watched our man there, and I pick things up quickly; also, you learned to do all sorts of things in Ultramar, particularly skills pertaining to repairing or improvising equipment, most of which we got from the enemy, with holes in it. When I decided to specialise, it was a toss-up whether I was going to be a sword-smith or an armourer. Literally; I flipped a coin for it. I lost the toss, and here I am.

Did I mention that I have my own water-wheel? I built it myself and I’m ridiculously proud of it. I based it on one I saw (saw, inspected, then set fire to) in Ultramar. It’s overshot, with a twelve-foot throw, and it runs off a stream that comes tumbling and bouncing down the hill and over a sheer cliff where the hillside’s fallen away. It powers my grindstone and my trip-hammer, the only trip-hammer north of the Vossin, also built by me. I’m a clever bugger.

You can’t forge-weld with a trip-hammer; you need to be able to see what you’re doing, and feel the metal flowing into itself. At least, I can’t; I’m not perfect. But it’s ideal for working the finished material down into shape, takes all the effort out of it, though by God you have to concentrate. A light touch is what you need. The hammer-head weighs half a ton. I’ve had so much practice I can use it to break the shell on a boiled egg.

I also made spring-swedges, for putting in fullers and profiling the edges of the blade. You can call it cheating if you like; I prefer to call it precision and perfection. Thanks to the trip-hammer and the swedges I get straight, even, flat, incrementally distal-tapered sword-blades that don’t curl up like corkscrews when you harden and quench them; because every blow of the hammer is exactly the same strength as the previous one, and the swedges allow no scope for human error, such as you inevitably get trying to judge it all by eye.

If I were inclined to believe in gods, I think I’d probably worship the trip-hammer even though I made it myself. Reasons; first, it’s so much stronger than I am, or any man living, and tireless, and those are essential qualities for a god. It sounds like a god; it drowns out everything, and you can’t hear yourself think. Second, it’s a creator. It shapes things, turns strips and bars of raw material into recognisable objects with a use and a life of their own. Third, and most significant, it rains down blows, tirelessly, overwhelmingly, it strikes twice in the time it takes my heart to beat once. It’s a smiter, and that’s what gods do, isn’t it? They hammer and hammer and keep on hammering, till either you’re swaged into shape or you’re a bloody pulp.

“Is that it?” he said. I could tell he wasn’t impressed.

“It’s not finished. It has to be ground first.”

My grindstone is as tall as I am, a flat round sandstone cheese. The river turns it, which is just as well because I couldn’t. You have to be very careful, with the most delicate touch. It eats metal, and heats it too, so if your concentration wanders for a split second, you’ve drawn the temper and the sword will bend like a strip of lead. But I’m a real artist with a grindstone. I wrap a scarf three times round my nose and mouth, to keep the dust from choking me, and wear thick gloves, because if you touch the stone when it’s running full tilt, it’ll take your skin off down to the bone before you can flinch away. When you’re grinding, you’re the eye of a storm of white and gold sparks. They burn your skin and set your shirt on fire, but you can’t let little things like that distract you.

Everything I do takes total concentration. Probably that’s why I do this job.

I don’t do fancy finishes. I say, if you want a mirror, buy a mirror. But my blades take and keep an edge you can shave with, and they come compass.

“Is this strictly necessary?” he asked, as I clamped the tang in the vise.

“No,” I said, and reached for the wrench.

“Only, if you break it, you’ll have to start again from scratch, and I want to get on.”

“The best ever made,” I reminded him, and he gave me a grudging nod.

For that job I use a scroll monkey. It’s a sort of massive fork you use for bending scrollwork, if that’s your idea of a useful and productive life. It takes every last drop of my strength (and I’m no weakling), all to perform a test that might well wreck the thing that’s been my life and soul for the last ten days and nights, which the customer barely appreciates and which makes me feel sick to my stomach. But it has to be done. You bend the blade until the tip touches the jaw of the vise, then you gently let it go back. Out it comes from the vise, and you lay it on the perfectly straight, flat bed of the anvil. You get down on your knees, looking for a tiny hair of light between the edge of the blade and the anvil. If you see it, the blade goes in the scrap.

“Here,” I said, “come and look for yourself.”

He got down beside me. “What am I looking for, exactly?”

“Nothing. It isn’t there. That’s the point.”

“Can I get up now, please?”

Perfectly straight; so straight that not even light can squeeze through the gap. I hate all the steps on the way to perfection, the effort and the noise and the heat and the dust, but when you get there, you’re glad to be alive.

I slid the hilt, grip, and pommel down over the tang, fixed the blade in the vise, and peened the end of the tang into a neat little button. Then I took the sword out of the vise and offered it to him, hilt first. “All done,” I said.

“Finished?”

“Finished. All yours.”

I remember one kid I made a sword for, an earl’s son, seven feet tall and strong as a bull. I handed him his finished sword; he took a good grip on the hilt, then swung it round his head and brought it down full power on the horn of the anvil. It bit a chunk out, then bounced back a foot in the air, the edge undamaged. So I punched him halfway across the room. You clown, I said, look what you’ve done to my anvil. When he got up, he was in tears. But I forgave him, years later. There’s a thrill when you hold a good sword for the first time. It sort of tugs at your hands, like a dog wanting to be taken for a walk. You want to swish it about and hit things with it. At the very least, you do a few cuts and wards, on the pretext of checking the balance and the handling.