По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

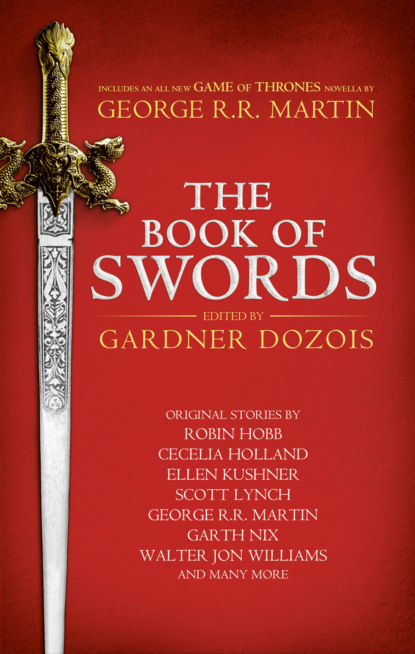

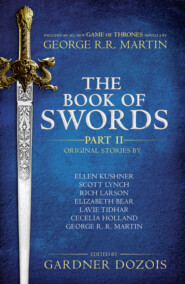

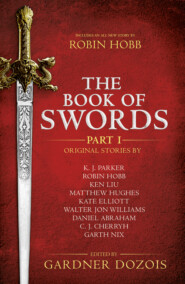

The Book of Swords

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But the bhikkuni was already gone, leaving behind a few loose strands of grey hair floating gently to the floor in the slanted rays of the sunlight. My father, stunned, held his hand against the side of his face where the dagger had brushed against his skin.

The hairs landed; my father removed his hand. There was a patch of denuded skin on his cheek, as pale as the stone slabs of the road in the morning sun. No blood.

“Do not be afraid, Daughter. I will triple the guards tonight. The spirit of your dear departed mother will guard you.”

But I’m afraid. I am afraid. I think about the glow of sunlight around the nun’s head. I like my long, thick hair, which the maids tell me resembles my mother’s, and she had combed her hair a hundred times each night before she went to sleep. I don’t want to have my head shaved.

I think about the glint of metal in the nun’s hand, quicker than the eye can follow.

I think about the strands of hair from my father’s beard drifting to the floor.

The light from the oil lamp outside the closet door flickers. I scramble to the corner of the closet and squeeze my eyes tightly shut.

There is no noise. Just a draft that caresses my face. Softly, like the flapping wings of a moth.

I open my eyes. For a moment, I don’t understand what I’m seeing.

Suspended about three feet from my face is an oblong object, about the size of my forearm and shaped like the cocoon of a silkworm. Glowing like a sliver of the moon, it gives off a light that is without warmth, shadowless. Fascinated, I crawl closer.

No, an “object” isn’t quite right. The cold light spills out of it like melting ice, along with the draft that whips my hair about my face. It is more like the absence of substance, a rip in the murky interior of the cabinet, a negative object that consumes darkness and turns it into light.

My throat feels parched and I swallow, hard. Fingers trembling, I reach out to touch the glow. A half second of hesitation, then I make contact.

Or no contact. There is no skin-searing heat nor bone-freezing chill. My impression of the object as a negative is confirmed as my fingers touch nothing. And neither do they emerge from the other side—they’ve simply vanished into the glow, as though I’m plunging my hand into a hole in space.

I jerk my hand back out and examine my fingers, wiggling them. No damage as far as I can see.

A hand reaches out from the rip, grabs my arm, and pulls me toward the light. Before I can scream, blazing light blinds me, and I’m overwhelmed by the sensation of falling, falling from the tip of a heaven-reaching pagoda tree toward an earth that never comes.

The mountain floats among the clouds like an island.

I’ve tried to find my way down, but always, I get lost among the foggy woods. Just go down, down, I tell myself. But the fog thickens until it takes on substance, and no matter how hard I push, the wall of clouds refuses to yield. Then I have no choice but to sit down, shivering, wringing the condensation out of my hair. Some of the wetness is from tears, but I won’t admit that.

She materializes out of the fog. Wordlessly, she beckons me to follow her back up the peak; I obey.

“You’re not very good at hiding,” she says.

There is no response to that. If she could steal me from a cabinet inside a general’s house guarded by walls and soldiers, I suppose there’s nowhere I can hide from her.

We emerge from the woods back onto the sun-drenched peak. A gust of wind brushes past us, whipping up the fallen leaves into a storm of gold and crimson.

“Are you hungry?” she asks, her voice not unkind.

I nod. Something about her tone catches me off guard. Father never asks me if I’m hungry, and I sometimes dream of my mother making me a breakfast of freshly baked bread and fermented beans. It’s been three days since the bhikkhuni had taken me here, and I’ve not eaten anything but some sour berries I found in the woods and a few bitter roots I dug from the ground.

“Come along,” she says.

She takes me up a zigzagging path carved into the face of a cliff. The path is so narrow that I dare not look down but shuffle along, my face and body pressed against the rock face and my outstretched hands clinging to dangling vines like a gecko. The bhikkhuni, on the other hand, strides along the path as though she’s walking in the middle of a wide avenue in Chang’an. She waits patiently at each turn for me to catch up.

I hear the faint sounds of clanking metal above me. Having dug my feet into depressions along the path and tested the vine in my hands to be sure it’s rooted securely to the mountain, I look up.

Two young women, about fourteen years of age, are fighting with swords in the air. No, fighting isn’t quite the right word. It’s more accurate to call their movements a dance.

One of the women, dressed in a white robe, pushes off the cliff with both feet while holding on to a vine with her left hand. She swings away from the cliff in a wide arc, her legs stretched out before her in a graceful pose that reminds me of the apsaras—flying nymphs who make their home in the clouds—painted on scrolls in the temples. The sword in her right hand glints in the sunlight like a shard of heaven.

As her sword tip approaches her opponent on the cliff, the other woman lets go of the vine she’s hanging on to and leaps straight up. The black robe billows around her like the wings of a giant moth, and as her ascent slows, she flips herself at the apex of her arc and tumbles toward the woman in white like a diving hawk, her sword arm leading as a beak.

Clang!

The tips of their swords collide, and a spark lights up the air like an exploding firework. The sword in the hand of the woman in black bends into a crescent, slowing her descent until she is standing inverted in the air, supported only by the tip of her adversary’s blade.

Both women punch out with their free hands, palms open.

Thump!

A crisp blow reverberates in the air. The woman in black lands against the mountain face, where she attaches herself by deftly wrapping a vine around her ankle. The woman in white completes her arced swing back to the rock, and, like a dragonfly dipping its tail into the still pond, pushes off again for another assault.

I watch, mesmerized, as the two swordswomen pursue, dodge, strike, feint, punch, kick, slash, glide, tumble, and stab across the webbing of vines over the face of the sheer cliff, thousands of feet above the roiling clouds below, defying both gravity and mortality. They are graceful as birds flitting across a swaying bamboo forest, quick as mantises leaping across a dew-dappled web, impossible as the immortals of legends whispered by hoarse-voiced bards in teahouses.

Also, I notice with relief that they both have thick, flowing, beautiful hair. Perhaps shaving is not required to be the bhikkhuni’s student.

“Come,” the bhikkhuni beckons, and I obediently make my way over to the small stone platform jutting into the air from the bend in the path. “I guess you really are hungry,” she observes, a hint of laughter in her voice. Embarrassed, I close my jaw, still hanging open from shock at seeing the sparring girls.

With the clouds far below our feet and the wind whipping around us, it feels like the world I’ve known all my life has fallen away.

“Here.” She points to a pile of bright pink peaches at the end of the platform, each about the size of my fist. “The hundred-year-old monkeys who live in the mountains gather these from deep in the clouds, where the peach trees absorb the essence of the heavens. After eating one of these, you won’t be hungry for a full ten days. If you become thirsty, you can drink the dew from the vines and the springwater in the cave that is our dormitory.”

The two sparring girls have climbed down from the cliff onto the platform behind us. They each take a peach.

“I will show you where you’ll sleep, Little Sister,” says the girl in white. “I’m Jinger. If you get scared from the howling wolves at night, you can crawl into my bed.”

“I’m sure you’ve never had anything as sweet as this peach,” says the girl in black. “I’m Konger. I’ve studied with Teacher the longest and know all the fruits of this mountain.”

“Have you had pagoda-tree flowers?” I ask.

“No,” she says. “Maybe someday you can show me.”

I bite into the peach. It is indescribably sweet and melts against my tongue as though it’s made of pure snow. Yet, as soon as I’ve swallowed a mouthful, my belly warms with the heat of its sustenance. I believe that the peach really will last me ten days. I’ll believe anything my teacher tells me.

“Why have you taken me?” I ask.

“Because you have a talent, Yinniang,” she says.

I suppose that is my name now. The Hidden Girl.

“But talents must be cultivated,” she continues. “Will you be a pearl buried in the mud of the endless East Sea, or will you shine so brightly as to awaken those who only doze through life and light up a mundane world?”

“Teach me to fly and fight like them,” I say, licking the sweet peach juice from my hands. I will become a great thief, I tell myself. I will steal my life back from you.