По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

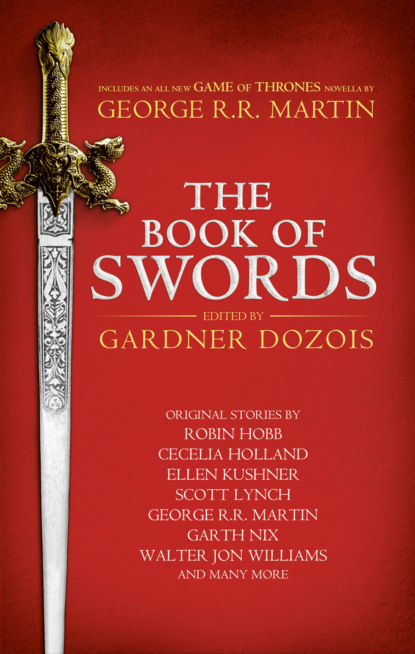

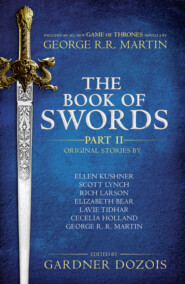

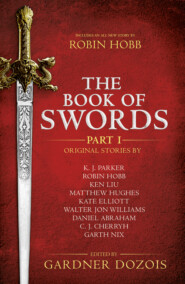

The Book of Swords

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She nods thoughtfully and looks into the distance, where the setting sun has turned the clouds into a sea of golden splendor and crimson gore.

Six years later:

The wheels of the donkey cart grind to a stop.

Without warning, Teacher rips the blindfold away from my eyes and digs out the silk plugs in my ears. I struggle against the sudden bright sun and the sea of noise—the braying of donkeys; the whinnying of horses; the clanging of cymbals and the wailing of erhus from some folk-opera troupe; the thumping and thudding of goods being loaded and unloaded; the singing, shouting, haggling, laughing, arguing, pontificating that make up the symphony of a metropolis.

While I’m still recovering from my journey in the swaying darkness, Teacher has jumped down to the ground to leash the donkey to a roadside post. We’re in some provincial capital, that much I know—indeed, the smell of a hundred different varieties of fried dough and candied apples and horse manure and exotic perfume already told me as much even before the blindfold was off—but I can’t tell exactly where. I strain to catch snippets of conversation from the bustling city around me, but the topolect is unfamiliar.

The pedestrians passing by our cart bow to Teacher. “Amitabha,” they say.

Teacher holds up a hand in front of her chest and bows back. “Amitabha,” she says back.

I may be anywhere in the empire.

“We’ll have lunch, then you can rest up at the inn over there,” says Teacher.

“What about my task?” I ask. I’m nervous. This is the first time I’ve been away from the mountain since she’s taken me.

She looks at me with a complicated expression, halfway between pity and amusement. “So eager?”

I bite my bottom lip, not answering.

“You will choose your own method and time,” she says, her tone as placid as the cloudless sky. “I’ll be back on the third night. Good hunting.”

“Keep your eyes open and your limbs loose,” she said. “Remember everything I’ve taught you.”

Teacher had summoned two mist hawks from nearby peaks, each the size of a full-grown man. Iron blades extended from their talons, and steel glinted from their vicious curved beaks. They circled above me, alternately emerging from and disappearing into the cloud-mist, their screeches mournful and proud.

Jinger handed me a small dagger about five inches in length. It seemed utterly inadequate for the task. My hand shook as I wrapped my fingers around the handle.

“What can be seen is not all,” she said.

“Be aware of what is hidden,” Konger added.

“You will be fine,” Jinger said, squeezing my shoulder.

“The world is full of illusions cast by the unseen Truth,” Konger said. Then she leaned in to whisper in my ear, her breath warm against my cheek, “I still have a scar on the back of my neck from my time with the hawks.”

They backed off and faded into the mist, leaving me alone with the raptors and Teacher’s voice coming from the vines above me.

“Why do we kill?” I asked.

The hawks took turns swooping down, feinting and testing my defenses. I leapt out of the way reflexively, brandishing my dagger to ward them off.

“This is a time of chaos,” Teacher said. “The great lords of the land are filled with ambition. They take everything they can from the people they’re sworn to protect, shepherds who have turned into wolves preying on their flocks. They increase the taxes until all the walls in their palaces are gleaming with gold and silver; they take sons away from mothers until their armies swell like the current of the Yellow River; they plot and scheme and redraw lines on maps as though the country is nothing but a platter of sand, upon which the peasants creep and crawl like terrified ants.”

One of the hawks turned to dive at me. A real attack, not a test. I crouched into a defensive stance, the dagger in my right hand held up to guard my face, my left hand on the ground for stability. I kept my eyes on the hawk, letting everything fade into the background except the bright reflections from the sharp beak and talons, like a constellation in the night sky.

The hawk loomed in my vision. A light breeze brushed the back of my neck. The raptor extended its talons and flapped its wings, trying to slow its dive at the last minute.

“Who is to say that one governor is right? Or that another general is wrong?” she asked. “The man who seduces his lord’s wife may be doing so to get close to a tyrant and exact vengeance. The woman who demands rice for the peasantry from her patron may be doing so to further her own ambition. We live in a time of chaos, and the only moral choice is to be amoral. The great lords hire us to strike at their enemies. And we carry out our missions with dedication and loyalty, true and deadly as a crossbow bolt.”

I got ready to spring out of my crouch to slash at the hawk, then I remembered the words of my sisters.

“ … What can be seen is not all … I still have a scar on the back of my neck.”

I dropped to the ground and rolled to the left, the talons of the hawk who had been trying to sneak up behind me missing only by inches. It collided with its companion in the spot where my head had been but a moment ago like a diver meeting her reflection at the surface of the pool. There was a tangle of beating wings and angry screeching.

I lunged at the storm of feathers. One, two, three slashes, quicker than lightning. The hawks tumbled down, their wings crumpling as they struck the ground. Blood from the clean cuts in their throats pooled on the stone platform.

There was also blood seeping from my shoulder where the rough rocks had scraped the skin during my roll. But I had survived, and my foes had not.

“Why do we kill?” I asked again, still panting from the exertion. I had killed wild apes before, and forest panthers and bamboo-grove tigers. But a pair of mist hawks were the hardest kill yet, the height of the assassin’s art. “Why do we serve as the talons of the powerful?”

“We are the winter snowstorm descending upon a house rotten with termites,” she said. “Only by hurrying the decay of the old can we bring about the rebirth of the new. We are the vengeance of a weary world.”

Jinger and Konger emerged from the mist to sprinkle corpse-dissolving powder on the hawks and to bandage my wound.

“Thank you,” I whispered.

“You need to practice more,” said Jinger, but her tone was kind.

“I have to keep you alive.” Konger’s eyes flashed mischievously. “You promised to get me some pagoda-tree flowers, remember?”

The thin crescent of the moon hangs from the tip of a branch of the ancient pagoda tree outside the governor’s mansion as the night watchman rings the midnight hour. The shadows in the streets are thick as ink, the same color as my silk leggings, tight tunic, and the cloth mask over my nose and mouth.

I’m upside down, my feet hooked to the top of the wall and my body pressed against the flat surface like a clinging vine. Two soldiers pass below me on their patrol route. If they looked up, they’d think I was just a part of the shadows or a sleeping bat.

As soon as they’re gone, I arch my back and flip onto the wall. I scramble along the top, quieter than a cat, until I’m opposite the roof of the central hall of the compound. Snapping my coiled legs, I sail across the gap in a single leap and melt into the shingles on the gentle curve of the roof.

There are, of course, far stealthier ways to break into a well-protected compound, but I like to stay in this world, to remain surrounded by the night breeze and the distant hoots of the owl.

Carefully, I pry off a glazed roofing tile and peek into the gap. Through the latticed under-roof I see a brightly lit hall paved with stones. A middle-aged man sits on a dais at the eastern end, his eyes intent upon a bundle of papers, flipping through the pages slowly. I see a birthmark the shape of a butterfly on his left cheek and a jade collar around his neck.

He is the jiedushi I’m supposed to kill.

“Steal his life, and your apprenticeship will be completed,” Teacher said. “This is your last test.”

“What has he done that he deserves to die?” I asked.

“Does it matter? It is enough that a man who once saved my life wants this man to die, and that he has paid handsomely for it. We amplify the forces of ambition and strife; we hold on to only our code.”

I crawl over the roof, my palms and feet gliding over the tiles smoothly, making no sound—Teacher trained us by having us glide across the valley lake in March, when the ice is so thin that even squirrels sometimes fall through and drown. I feel one with the night, my senses sharpened like the tip of my dagger. Excitement is tinged with a hint of sorrow, like the first stroke of the paintbrush on a fresh sheet of paper.

Now that I’m directly above where the governor is sitting, once again I pry off one tile, then another. I make a hole big enough for me to slink through. Then I take out the grappling hook from my pouch—painted black to prevent reflections—and toss it to the apex ridge so that the claws dig in securely. Then I tie the silk cord around my waist.

I look down through the hole in the roof. The jiedushi is still where he was, oblivious to the mortal danger over his head.